- Industry

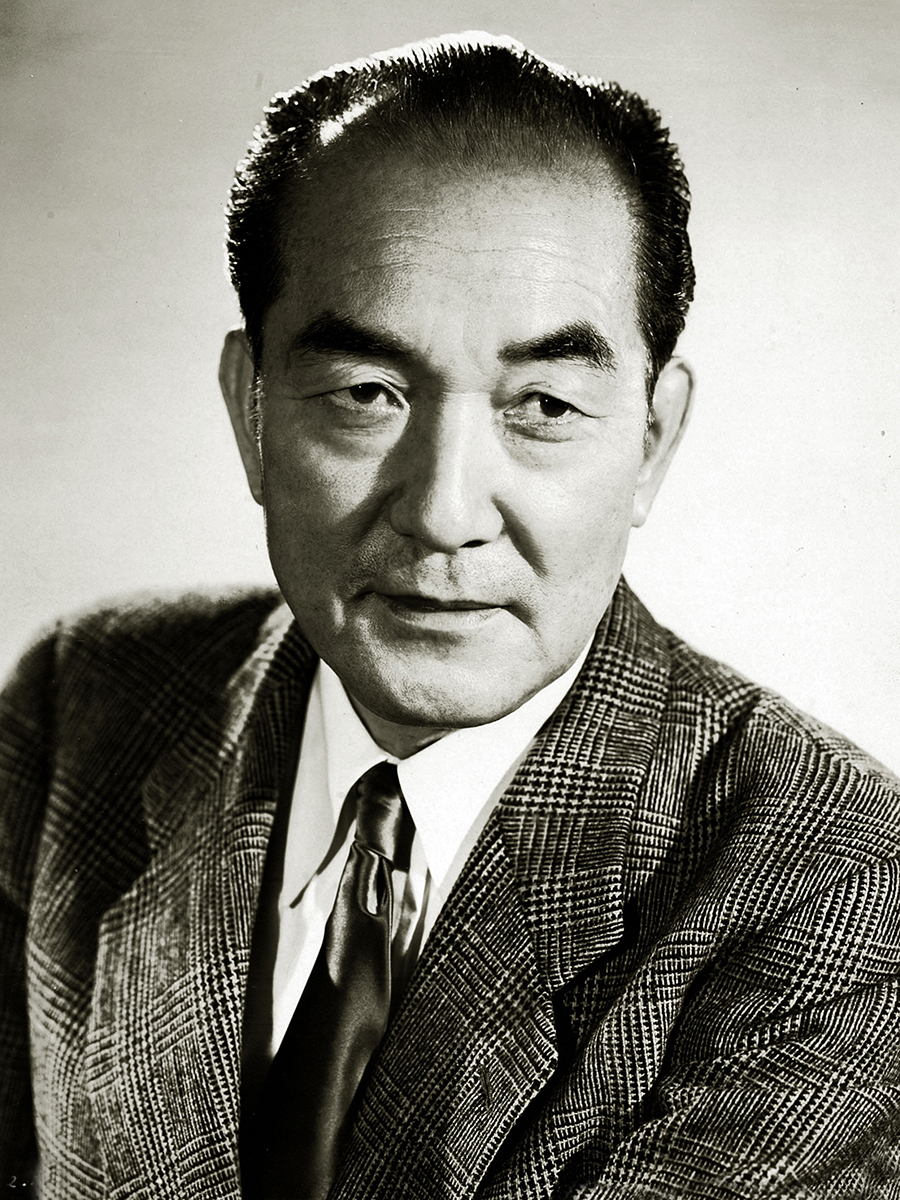

Forgotten Hollywood: Sessue Hayakawa Always Wanted to Play a Hero

In the pantheon of matinee idols of the silent film era in Hollywood was an unlikely star, Japanese actor Sessue Hayakawa, who had legions of fans and earned $7,500 a week in his heyday for movies like Cecil B. DeMille’s 1915 The Cheat, The Tong Man and An Arabian Knight.

Famous in the days of the anti-miscegenation laws, he never got the (white) girl in his movies. He played opposite Bessie Love, Blanche Sweet, Zasu Pitts, and Florence Vidor. “Every other plot contrivance leads to boy-gets-girl. This contrivance would lead to boy-does-not-get-girl,” Hayakawa scholar Stephen Gong of the Pacific Film Archive told the Deseret News.

One theory for his fame as a sex symbol and romantic hero, according to author Daisuke Miyao in his book Sessue Hayakawa: Silent Cinema and Transnational Stardom quoting a critic, was his appeal “to a latent female urge to experience sex with a beautiful but savage man of another race.”

Hayakawa also played non-Japanese roles – an Indian rebel, an American Indian, a Chinese warrior, and a Burmese ivory trader (in The Cheat, his breakthrough film).

It is remarkable enough that the handsome and athletic star broke barriers with his acting career, but in 1919, Hayakawa broke new ground when he set up a production company in Hollywood. To do so, he turned down an offer to play the lead in The Sheik, the role that would make Rudolf Valentino a star. He would go on to make 23 films, the best known of which is The Dragon Painter, lauded as an artistic achievement. In it, Hayakawa plays a painter who is searching for a stolen princess from another life.

Sessue Hayakawa was born in Kintaro Hayakawa in Chiba, Japan in 1886. An injury derailed the naval career he aspired to and he attempted suicide a couple of times before his father sent him to the US to study at the University of Chicago, where he was a star on the football team. In Los Angeles after his studies to catch a boat back home, Hayawaka fell in with the Japanese Theatre in Little Tokyo and performed in their productions, catching the eye of film producer Thomas H. Ince. So was born a Hollywood career. He got a contract with the Famous-Players Lasky (Paramount Pictures in those days) and thus got his shot with deMille in The Cheat.

A lot of Hayakawa’s silent films are lost, but prominent amongst those that are saved are The City of Dim Faces and His Birthright (1918) with Marin Sais, and The Temple of Dusk (1918) with Jane Novak.

According to Goldsea.com, a magazine for Asian Americans, Hayakawa drove a gold-plated Pierce-Arrow and threw wild parties for his friends in the castle-like mansion (now destroyed) he bought on Franklin Avenue and Argyle Street that was well-stocked with liquor before Prohibition took effect in 1920.

In 1922, Hayakawa left Hollywood. He appeared on Broadway in Tiger Lily in 1923, and made two films in London, The Great Prince Shan and The Story of Su, both in 1924. He had fans in France, Germany, and Russia. He remained in France for much of World War II.

Returning to the US, he started the next chapter of his Hollywood career, starting with Tokyo Joe opposite Humphrey Bogart in 1949. His performance as Colonel Saito in The Bridge on the River Kwai earned him a Golden Globe nomination.

Considering the barriers that Hayakawa broke and the stardom he achieved, it is surprising that he is not better known or celebrated in Hollywood history. Battling racism, miscegenation laws that limited his roles, and typecasting, he became the first non-white international movie star. He could not even become a US citizen according to the laws at the time.

According to Army Archerd writing in Variety in 1957: “Back in 1949, Hayakawa admitted, ‘My one ambition is to play a hero.’”

Hayakawa died in Tokyo in 1973 from cerebral thrombosis. He is buried in Toyama, Japan.