- Industry

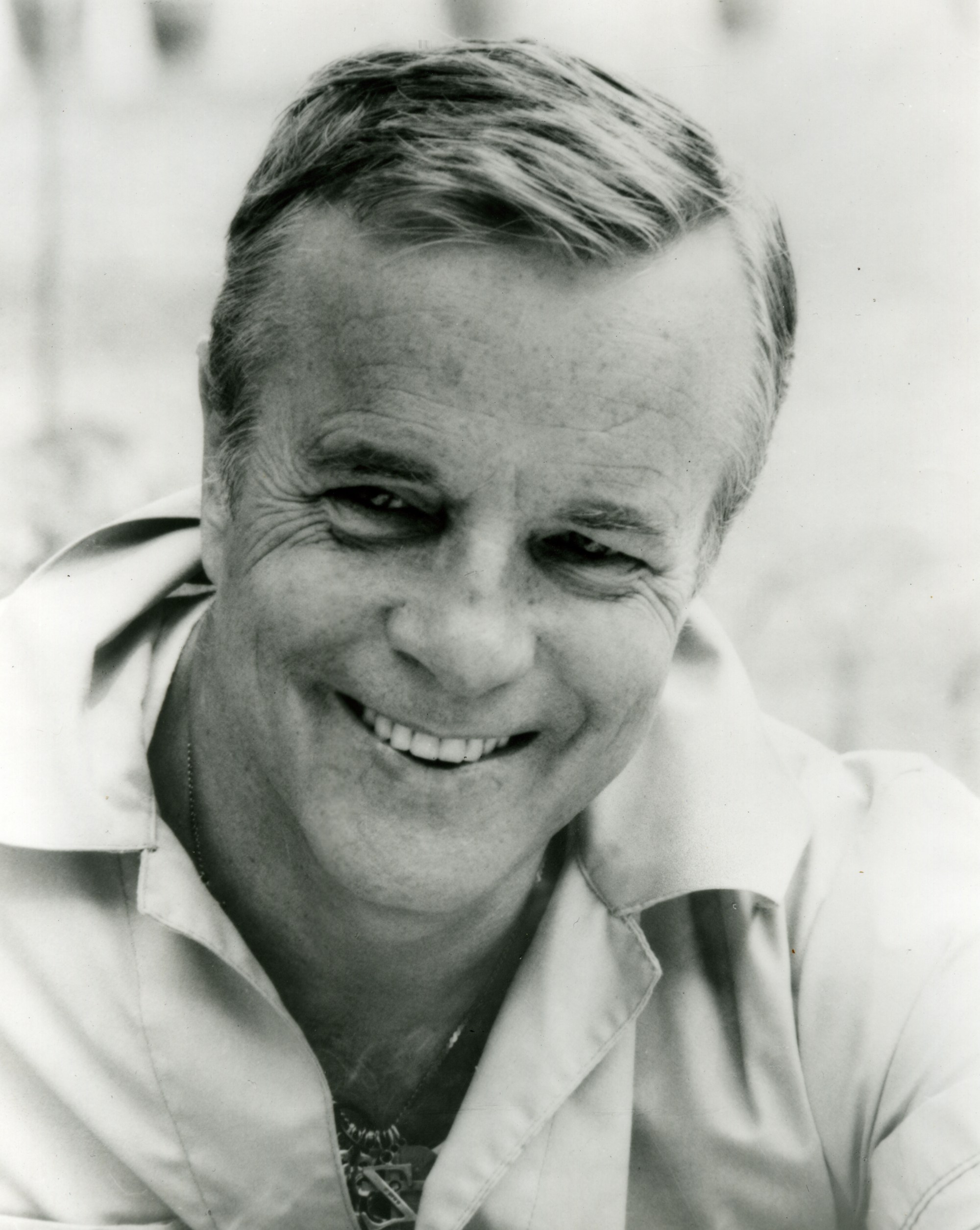

Franco Zeffirelli, Florentine Renaissance Man, 1923-2019

Franco Zeffirelli, who died recently at 96, was Italian to his core, but also had a life long love of England, and won his Golden Globe for directing a movie in English with an all British cast, based on a Shakespeare play, Romeo and Juliet, in 1968. The movie won the Best English Language Foreign Film, a discontinued Golden Globe category. The leads, Leonardo Whiting and Olivia Hussey both took home Golden Globes in another discontinued category, New Star of the Year (actor and actress). Zeffirelli and his longtime composer and collaborator Nino Rota were nominated but did not win. (Paul Newman was named Best Director for Rachel Rachel. Rota would win his Golden Globe in 1972, for The Godfather).

After wins by gritty, kitchen-sink British dramas (Alfie and Darling) in this category, the zeitgeist was ready for a lush romantic drama, a tragic love story of two flower children. The audiences embraced Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet, the first screen version to feature leads who were close in age to the characters of the original play, and to youthful audiences of the turbulent 1960s.

At the time it was the most financially successful adaptation of a Shakespeare play and the critics lavished praise on Zeffirelli. Roger Ebert called it ‘the most exciting film of Shakespeare ever made’, and Rotten Tomatoes gives the movie a score of 94%, declaring it recently ‘the definitive cinematic adaptation of the play’.

Zeffirelli’s early life was troubled and traumatized. He was born in Florence, Italy, to a dressmaker and her drapery merchant lover, while both were married to others. Young Franco was called a bastard in public. His mother died when he was six, and his school teacher, a priest, sexually abused him. He found refuge in the arts: first at the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence and later at the architecture faculty of Florence University. World War II intervened, and Franco joined the resistance. Returning to Florence after the war, he decided that the theater interested him more than architecture. While working as a scene painter, he met the director Luchino Visconti, who cast him in a play, and Franco was hooked.

It was the start of a long term personal and professional relationship. Zeffirelli was assistant director on Luchino Visconti’s film La Terra Trema (1948), became intensely involved with him and moved into Visconti’s villa in Rome. Zeffirelli later called it one of his “serious love affairs”, in which he was “hit right on the forehead and in the heart”. Zeffirelli became an accomplished designer and art director for Visconti and then moved on to design for the La Scala opera house in Milan and to direct there too. His success in Milan led to a parallel success in England. Invited to London in 1959 to direct Lucia di Lammermoor at Covent Garden with newcomer soprano Joan Sutherland, he stunned the British audience with his realistic staging and was invited a year later to direct an “Italian-style” Romeo and Juliet at the Old Vic, starring a young Judi Dench. It was Zeffirelli’s first go at the Shakespeare play that would later bring him Golden Globe honors.

The director would spend the next decade moving between the UK and Italy, working with A-list talent (who remained life long friends and collaborators), and often getting praise for bringing an Italian flair to British theater, staging Shakespeare plays and Italian operas. Othello with John Gielgud at Stratford-upon-Avon was well received, and Much Ado About Nothing at the National, in 1965 was a hit. He directed Maria Callas in Tosca at Covent Garden, and staged Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? in Venice, Italy (1963) with Monica Vitti and Hamlet in Italian at the Old Vic.

He crossed the ocean and conquered New York, with an elegant version of Verdi’s Falstaff, conducted by Leonard Bernstein, at the Metropolitan Opera House (1964) followed by several productions at the new opera house in Lincoln Center.

Next came cinema. His first major film was The Taming of the Shrew (1968), starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. It earned him a Golden Globe nomination for Best Motion Picture- Comedy or Musical. Guiding the high maintenance couple didn’t faze Zeffirelli, who wrote later in his autobiography: “I had already worked with difficult performers like Callas and Magnani so Liz and Richard didn’t scare me.”

The movie’s success led Paramount Studios to finance Romeo and Juliet which Zeffirelli co-wrote, and directed in English on location all over Italy. Costing a mere $1.5 million, the film grossed more than $50 million. “From Bronx to Bali, Shakespeare was a box-office hit,” Zeffirelli wrote. Teenagers flocked to see a Romeo and Juliet where, for the first time, the lead actors were teenagers. ‘

Zeffirelli was also nominated by the Academy for a best director Oscar but missed the ceremony. He was badly injured in a car accident, suffering head injuries and undergoing painful reconstructive surgeries. Many believed that the ordeal brought on his erratic behavior after his recovery. It was certainly the cause of his newfound religious zeal, as he believed that he was saved by divine intervention. He turned to religious themes with Brother Sun, Sister Moon (1972), a film about Saint Francis of Assisi, and Jesus of Nazareth (1977). a well-received TV mini-series.

He returned to feature films with a remake of The Champ (1979). Schmaltzy and manipulative, it was a box office success but a critical failure. Vincent Canby in the New York Times called it ‘a frontal assault on the emotions. Mr. Zeffirelli never aspired to subtlety,..there’s no pile-up of emotional garbage too big that it can’t be washed clean by a good cry..(and) people don’t cry in this film, they erupt. Mr. Zeffirelli orchestrates it as if it were ‘Tosca’.’ The young lead, Ricky Schroder won the Golden Globe for New Star of the Year in a Motion Picture.

Zeffirelli tried for another hit, going back to the Romeo and Juliet theme, updating it to modern times in Endless Love (1981) with Brooke Shields and Tom Cruise as the leads. Lionel Richie was nominated for a Golden Globe for his theme song, which he sang as a duet with Diana Ross, a Golden Globes winner (Lady Sings the Blues, 1972). While a moderate box office performer, critics savaged the movie and mocked Zeffirelli. Bette Midler, the Oscars presenter, called it ‘That Endless Bore’. The Razzie Awards bestowed five nominations, including Worst Picture and Worst Director. The Stinkers Bad Movie Awards nominated the movie for Worst Picture and Zeffirelli for ‘Worst Sense of Direction (‘Stop them before they direct again’). Both lost. It was, indeed, Zeffirelli’s last dramatic feature film. He went back to his main strengths- operas, music, stage, and Shakespeare.

There was a filmed version of Hamlet (1990), with Globe winner Mel Gibson in the lead role. A sumptuous staging of Carmen in Verona, and a stunning one-off production of Puccini’s Tosca at the Rome Opera House in 2000, starring Luciano Pavarotti. It demonstrated Zeffirelli’s range and versatility and was praised, this time, for its elegant simplicity. In 2002 he made a biopic, Callas Forever, about his longtime star and muse, and in 2006 he again stunned with the lavish sets and design of his production of Aida at La Scala, which the audience booed midway, but Zeffirelli declared to be “the sum of all the others – the Aida of Aidas”.

Ceaselessly active, he produced operas in Verona and Rome and found the time and energy to run for office, elected twice to serve in the senate. In his 90s he collected the highest accolades and recognition: an honorary knighthood from Britain, the lifetime achievement prize at the David di Donatello awards (the Italian film awards) and In 2013 he was given Florence’s highest honor, the Fiorino d’Oro, as befitting a modern Renaissance man.

With some 160 productions to his credit, Zeffirelli rode out his failures and basked in his much more numerous successes. He once said of himself: ‘I’m not the greatest director of opera in the world. I’m the only one.’ When asked what had kept him going long after many of his peers had retired he replied: ‘It’s the anticipation, the expectation, that’s what keeps you going,…So many things, it’s a miracle. A superior hand has helped in so many moments of my life.’

Franco Zeffirelli, a Renaissance man, always kept going.