- Film

HFPA-Sponsored Restorations Shown in Cannes Classics

One of the great sidebars in Cannes is the Classics selection, a favorite of cinephiles and a tribute to the history of cinema and the festival. This year fans can feast their eyes on great movies from Jean-Luc Godard’s Masculin Féminin, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris and Milos Forman’s Valmont. Included in the selection are three titles restored by The Film Foundation, a long-time HFPA grant recipient. Tomas Gutierrez Alea’s Memorias del Subdesarrollo, Kenzo Mizogughi’s Ugetsu Monogatari and Marlon Brando’s One-Eyed Jacks have all been restored by the Foundation. The HFPA’s Emanuel Levy reminds us why the latter, Marlon Brando’s only directorial effort, is an important and innovative film.

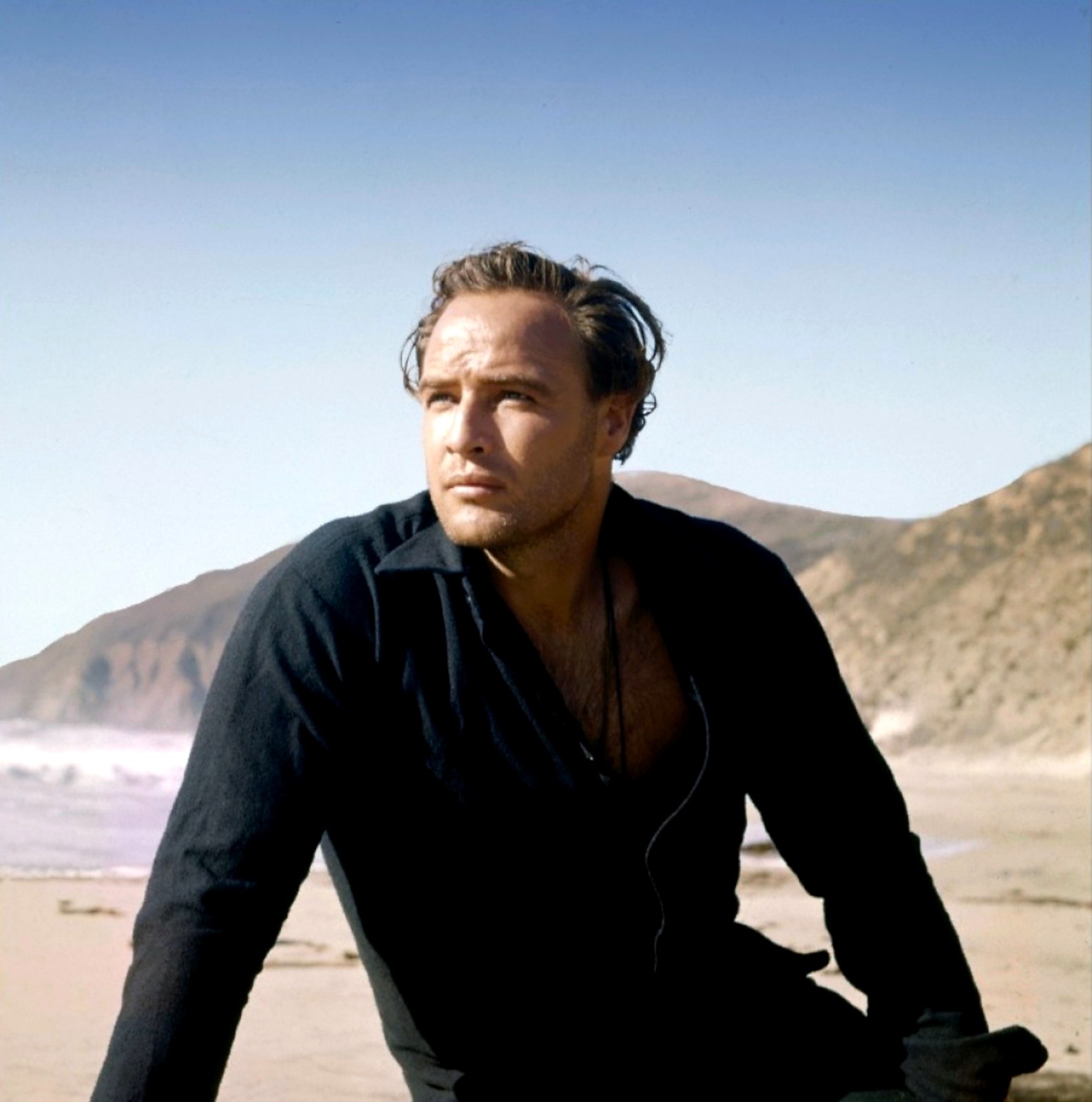

In addition to being a supremely gifted actor, Marlon Brando was also a talented director, as manifest in One-Eyed Jacks, his only helming effort and one of the most strangely compelling westerns of the 1960s. This interesting, vastly underestimated film, has now been restored and is shown as part of the impressive program of Cannes Classics at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival

A lot has been written about the making of the of One-Eyed Jacks, how Brando escalated the budget by an overly long production process. Originally budgeted at $1.8 million, Paramount claimed that the final cost was close to $6.0 million. Initially, Stanley Kubrick, whose pictures Brando admired, was hired as director, but he and Brando had "artistic differences"–they could not agree on the characterization, among other issues. As a result, Kubrick asked to be released and Brando took over the helming.

Tough and realistic yet in moments also moody and lyrical, One-Eyed Jacks is a classic tale of male camaraderie, betrayal, and revenge. The story begins with two American bandits operating in Mexico, Rio (Brando), a happy-go-lucky man who perceives himself as a Casanova, and Dad Longworth (Karl Malden), an older guy wishing to end his larcenous ways and settle down. The couple robs banks and spends their time drinking and courting woman; Rio gives the women that he likes his most "precious" possession, his mother's wedding ring.

The Mounted Police trail the pair but Rio and Dad fight their way out. The police follow and the bandits are trapped in the desert, when one of their horses is shot. Rio and Dad then toss a coin to determine who will ride off and who will stay. Dad wins but he promises to return and rescue Rio. However, Dad takes the proceeds from their robberies, grabs another horse at a ranch, and rides off for the border, leaving Rio to his devices. As a result, Rio is captured and spends five years in the Sonora Federal Prison before he escapes.

A man bent on revenge, Rio pursues Dad to Monterey, where he learns that his ex-partner is now the sheriff, married to a Mexican wife, Maria (Katy Jurado) and raising a teenage daughter, Louisa (Pina Pellicer). Dad becomes uneasy, when Rio and his stepdaughter show romantic interest in each other. During a fiesta, the bank remains closed, thus thwarting Rio's plans. Rio seduces Louisa as an act of contempt for Longworth but he cannot help but feel tender toward the girl. Rio and his partners retreat to a coastal fishing village, where he nurses himself back to health, while practicing with his gun. Amory and Johnson grow impatient and decide to make their own move, and when Modesto refuses to join them, they kill him. During an unexpected visit of Louisa at the village, Rio learns that she is pregnant and confesses his love for her. But revenge has become an all-consumming obsession with Rio.

When Amory and Johnson fail in their attempt to rob the bank, Rio is blamed and Longworth again arrests him, promising to hang him. Louisa visits him and brings a derringer, and Rio is able to overcome the vicious and cowardly deputy, Lon (Slim Pickens). Making his way to the street, he engages Dad Longworth in a gunfight, and kills him. Bidding farewell from Louisa, while promising to return, Rio rides away.

When the first cut of One-Eyed Jacks ran four hours and forty-two minutes, the movie was removed from Brando and butchered in the editing room. Producer Rosenberg and his editors spent months trimming the picture down to two hours and 21 minutes. After a long post-production period, the film was released in March 1961. When the film was finally released, Brando expressed publicly his dissatisfaction. He had been forced to change the ending. In Brando's version, the Mexican girl Louisa is killed in the gunfight, but Paramount considered this to be too gloomy and downbeat and insisted on a happier closure.

Initially, the film received mixed critical reaction, which did not help its commercial prospects. Even so, there is much to praise about the film–in either version. The acting is good, particularly of Brando and Malden (who had appeared together in 1951 in A Streetcar Named Desire, and in 1954 in On the Waterfront, both directed by Elia Kazan. As expected of actors-turned-directors, Brando indulges his actors with many close-ups and lingering reaction shots, and the tempo is slow by standards of mainstream Westerns.

Spectacularly shot by Charles Lang in Death Valley and the California coast, near Monterey, One-Eyed Jacks boasts sharp imagery (which was Oscar-nominated). It is still one of few westerns to include the unusual landscapes of ocean and beaches.