- Golden Globe Awards

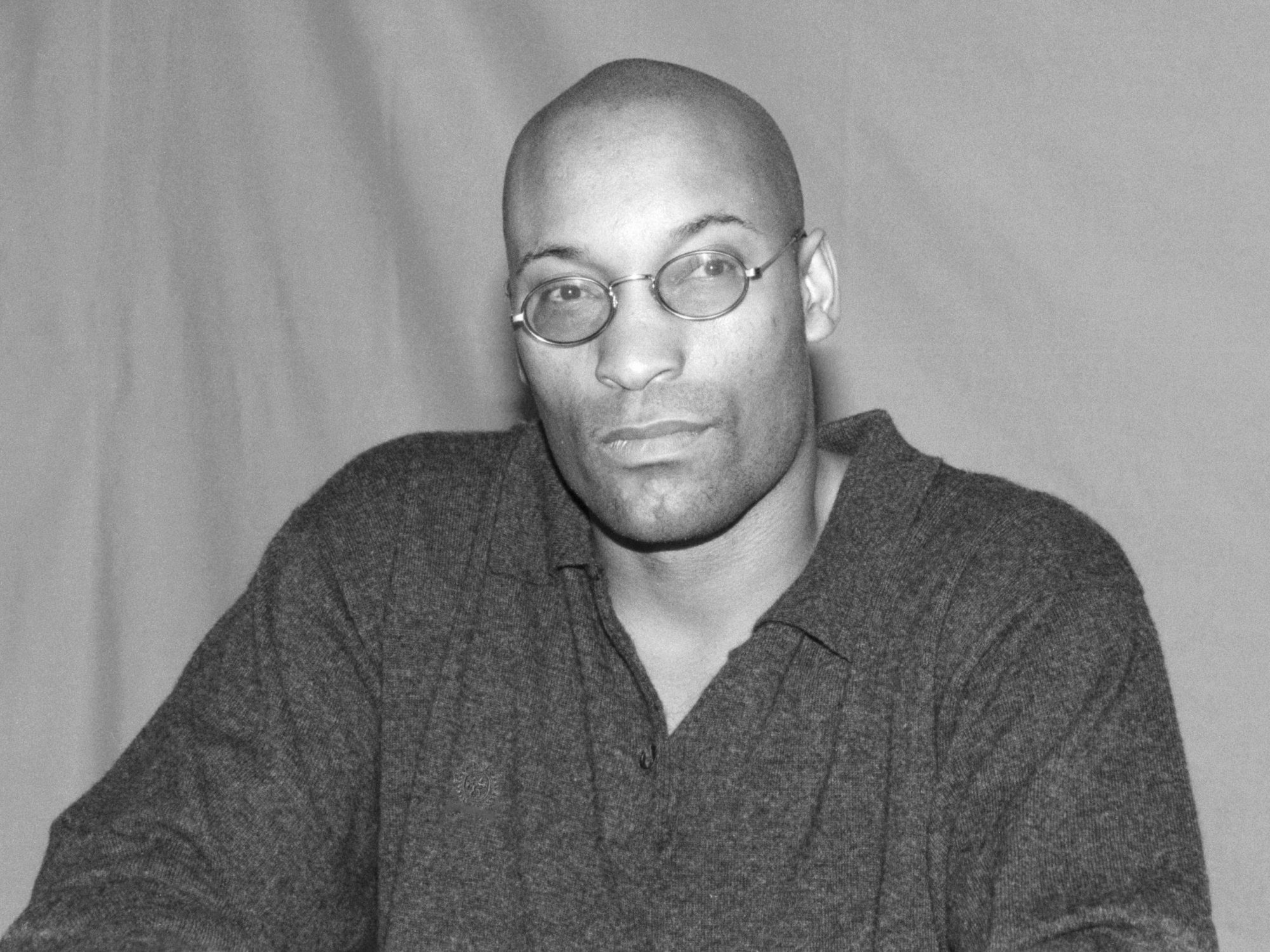

John Singleton, 1991 on “Boyz n the Hood” – Out of the Archives

John Singleton was honored with a tribute during the 2022-2023 Academic year by USC (University of Southern California), his alma mater, where he developed the script for his 1991 directing debut, Boyz n the Hood, while attending the screenwriting program at USC’s Film School (the school has since been renamed the School of Cinematic Arts, or SCA). For this film, Singleton was nominated for two Academy Awards in 1992 for Best Director and Best Screenplay. He was 24 at the time.

In August, 1991, the young filmmaker – along with producer Steve Nicolaides, actors Larry Fishburne, Cuba Gooding Jr., Morris Chestnut and Tyra Ferrell – gave an exclusive interview to the journalists of the Hollywood Foreign Press Association about Boyz n the Hood, a groundbreaking movie about three childhood friends growing up in the predominantly Black neighborhood of South Central Los Angeles.

Singleton would go on to direct movies like Poetic Justice (1993), Higher Learning (1995), Rosewood (1997), Shaft (2000), Baby Boy (2001), and Four Brothers (2005). He sadly passed away in 2019 at the age of 51.

Singleton explained how he conceived the character of Furious, inspired by his own father, and played by Larry Fishburne: “I consider Furious to be the anchor of the film. My original intent was to have someone who could be the ultimate father figure to a young Black boy growing up in that condition. The catalyst for this film for me was when I went from living with my mother to living with my father; he gave me focus and direction, then my whole life was changed. In a lot of ways this film is a tribute to my own father, so I tried to write down the philosophies that he taught me growing up and embody them.”

Fishburne added the three maxims that Furious imparted to his son Tre, played by Cuba Gooding, Jr.: “If you want something you can ask your father for it, because stealing isn’t necessary. Always look a person in eye, because that way they’ll respect you. And never respect anybody that doesn’t respect you back.”

Singleton talked about growing up in a black neighborhood in South Los Angeles and how he escaped the lure of drugs, not through schooling, but through his parents’ teachings: “Education is a very important tool, but one thing that transcends that is a strong family structure. I can remember my mother sitting down with me when I was in fourth or fifth grade to go over mathematical times tables and engrain them into my head, and then we’d work on divisions. My father didn’t have his own father around, but when he had a son, he said to himself, ‘I’m going to do something for my son.’ If an individual places an emphasis on thought and on forward progression, not only for himself and the people that he or she loves around them, then we can make this place a better world.”

Singleton went on to explain how he had benefited from his father’s warning about the dangers of a life of crime: “When I was 14 or 15, my father told me that the average life of a drug dealer is two to three years, if you’re lucky. He wouldn’t tell me, ‘Don’t do this,’ but he’d say, “If you go to jail, you’re on your own, I’m not coming to get you out.’ A lot of people that sell drugs, they do it for that all-encompassing American dream. If their little brother doesn’t have any school clothes, and their mother’s crying because they can’t pay the rent, if they’re having problems with the cops or with trying to get into a work program, then the only easy way out that’s afforded to them is to sell drugs. So people from my generation now are going through what I call a revisionist thought process about little ways in which to change the program, because there are other opportunities. There’s so many different levels of what is wrong and what is right in society, it’s a whole dichotomy, but when you get in this conversation about this subject, the ultimate thing that I try to tell people is to have focus and direction in their lives, that money is not the emphasis.”

This is how the writer-director interpreted the gang shootings that took places at several Southern California theaters on the movie’s opening night, July 12, 1991: “The real deal is that the killings that happened that Friday night had a lot to do with the condition of America right now. America as a country is under a state of siege, not with another nation but with itself, and it just so happens that there are certain people that don’t want to emphasize on that, on the problems that we have in terms of illiteracy, in terms of the large amount of poverty that goes on in this country, which is largely comparable to a lot of other nations. It was kind of unfair, because all that stuff got pinned on the film and not on the actual condition itself.”

Singleton acknowledged that the themes of Boyz n the Hood were universal, and resonated with what was happening, not just in California, but in other places, too: “The beautiful thing about the universality of this film is that it deals with a specific culture, time and place, but there are a lot of things that can be applied to what’s going on in different parts of the world. When I was going through high school, I really thought it was hip to go to different types of films with different types of visions. That’s when I saw a Brazilian film by Hector Babenco called Pixote (1981), about the problems that are happening in Rio, where most of the people that are homeless are children. It’s like the human condition becomes that much more powerful in films like Boyz n the Hood or Pixote or Cinema Paradiso (1988) by Giuseppe Tornatore. And it’s all a part of cinema. Cinema was created in the first place to record life, and life is not just one set of people, it is all-encompassing, and there are different forms of life.”