- Industry

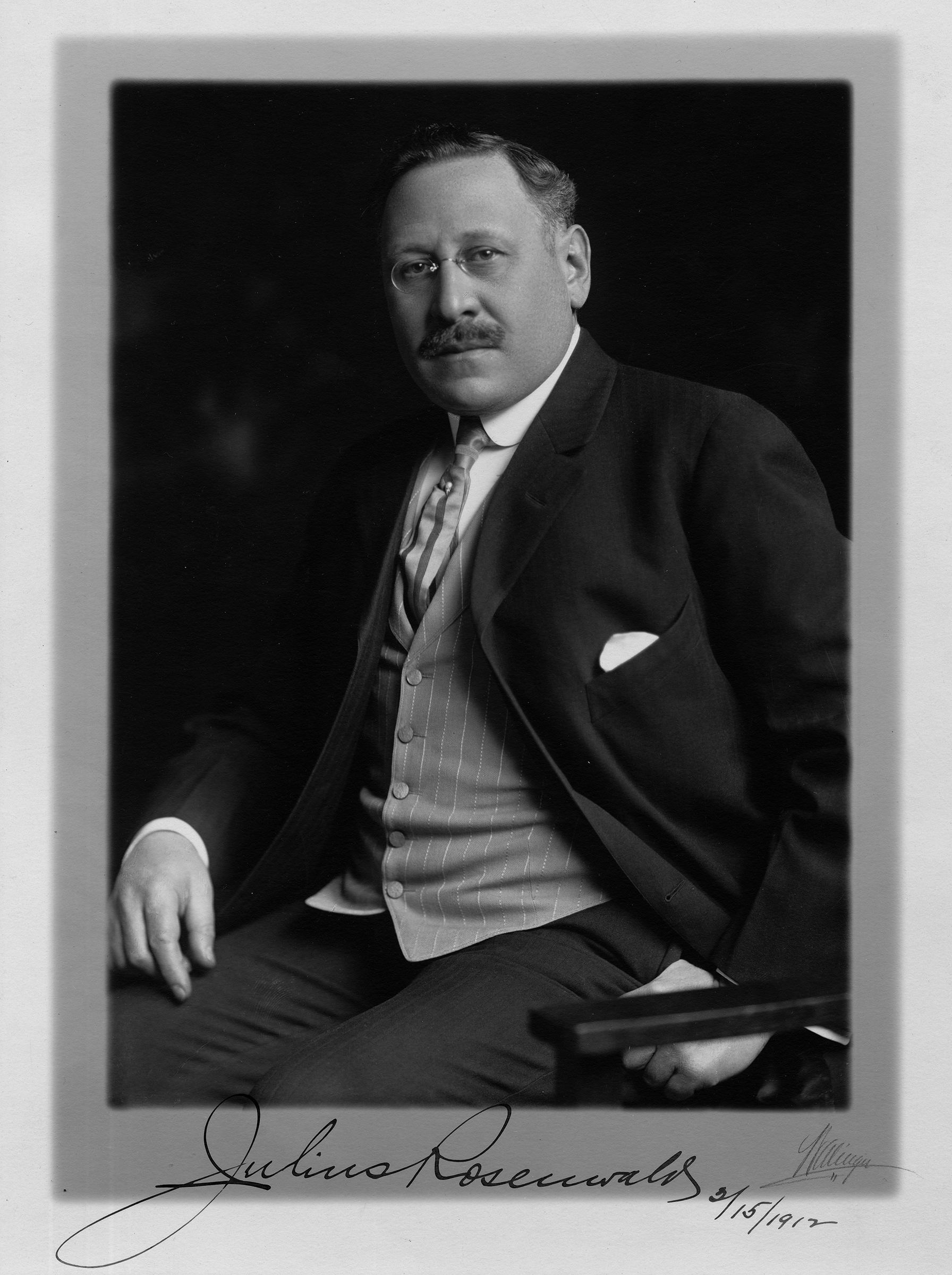

Julius Rosenwald – The Documentary

Aviva Kempner who recently met with the Hollywood Foreign Press Association as part of our Roundtable series talked about the documentary she made about businessman and philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, who partnered with Booker T. Washington and African American communities to build over 5,000 schools in the Jim Crow South, and whose Rosenwald Fund also provided grants to support a Who’s Who of African American artists and intellectuals.

Although the documentary is intended as a tribute to a great American philanthropist, it actually serves as a virtual history of Black oppression in this country. Rosenwald’s lifelong concern for African Americans was sparked by the 1908 race riots in Springfield Illinois. Two Black men had been arrested as suspects in the rape and murder of two young White women and the father of one of them. When a mob seeking to lynch the men discovered the sheriff had transferred the accused out of the city, the Whites furiously spread out to attack Black neighborhoods, murdered Black citizens on the streets and destroyed Black businesses and homes.

As a consequence, Rosenwald became a founding member of the NAACP where he met Booker T. Washington, a meeting that would change the course of Black education. When Black churches were being burned in the South, large numbers of African Americans migrated to Chicago, but upon arriving there they had nowhere to live, the customary YMCAs housed Whites only. To rectify this Rosenwald donated $25,000 to build the first YMCA to house Blacks and offered another $75,000 to build additional YMCAs for Blacks anywhere in America. Of course, this exodus was opposed by Southern farmers who needed African Americans to pick their cotton, and plant and harvest their corn and peanuts. And when President Taft invited Booker T. Washington to the White House, White America was outraged. Nevertheless, between 1913 and 1932, twenty-seven YMCAs were built for Black people.

Rosenwald was invited by Booker T, to visit Tuskegee University, and he was so impressed by what he saw there, how Tuskegee had been built by Black students to counter America’s economic need to keep Blacks uneducated, he decided to join the crusade. At the time Southern Black schools were segregated and unequal, one-room schoolhouses, where students were taught by teachers with no higher education. Rosenwald donated $680,000 to build 314 schools in rural America. His one proviso: one-third of the funds would have to come from him, another third from African Americans themselves, and a third from Whites. These schools he believed would be “for the people, by the people.”

By the time Booker T. died in 1915, Blacks had contributed way beyond their means. The schools flourished. One of many dedicated teachers who taught there was the mother of the great theater director George Wolfe.

Because of their success, members of the KKK burned down many of these schools, but Rosenwald promptly rebuilt them. All told 500 schools were built throughout the South, which, because of Rosenwald’s insistence, were built exclusively with African American labor.

1916 was the year of the Great Migration. For African Americans, Chicago was the promised land, where high paying jobs (compared to what they were used to in the South) offered opportunities for them as Pullman porters on the railroads, and work in the stockyards and the steel mills, equal pay regardless of color. Unfortunately, the only Black housing available offered dreadful living conditions; people were required to sleep in shifts, families shared one bedroom, but once again Rosenwald had a solution. He built a housing community that included a park and a playground, the Michigan Boulevard Garden Apartments, affectionately known as the Rosenwald. Among the families who lived there, the parents of poet Langston Hughes, opera star Marian Anderson, legend Quincy Jones, heavyweight champion Joe Louis, and Olympic medalist Jesse Owens.

Even more pervasive were the Rosenwald fellowships which offered $1,000 to promising African Americans. Among those who received them were medical pioneer Charles Drew, author James Walden Johnson, Nobel Prize winner Ralph Bunche, composer William Grant Still, and dancer Katherine Dunham.

A second great Migration to Harlem spawned the great African American renaissance, Among those who received Rosenwald fellowship were artist Jacob Lawrence, poet Langston Hughes, authors James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison, and photographer Gordon Parkes.

With the advent of World War 2, you’d think that things had changed for the better, but African Americans were still segregated and marginalized. The legendary Tuskegee Fighters were only allowed to join the fighting ranks thanks to the intervention of Eleanor Roosevelt. She was a Board member of the Rosenwald Fund.

Among the outstanding African Americans who pay heartfelt tribute to Julius Rosenwald in the documentary are congressmen Julian Bond and the recently deceased John Lewis, and Nobel Prize winner Maya Angelou. Incidentally, Rosenwald stipulated in his will that all his money be spent and not used to perpetuate his name. Those funds were depleted by 1948.

Since 2018 Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation has distributed DVDs of Rosenwald to elementary and secondary schools and colleges all over the country along with a teacher’s guide. Further screenings in this divisive time would go a long way in explaining why Americans have taken to the streets in such numbers.