- Golden Globe Awards

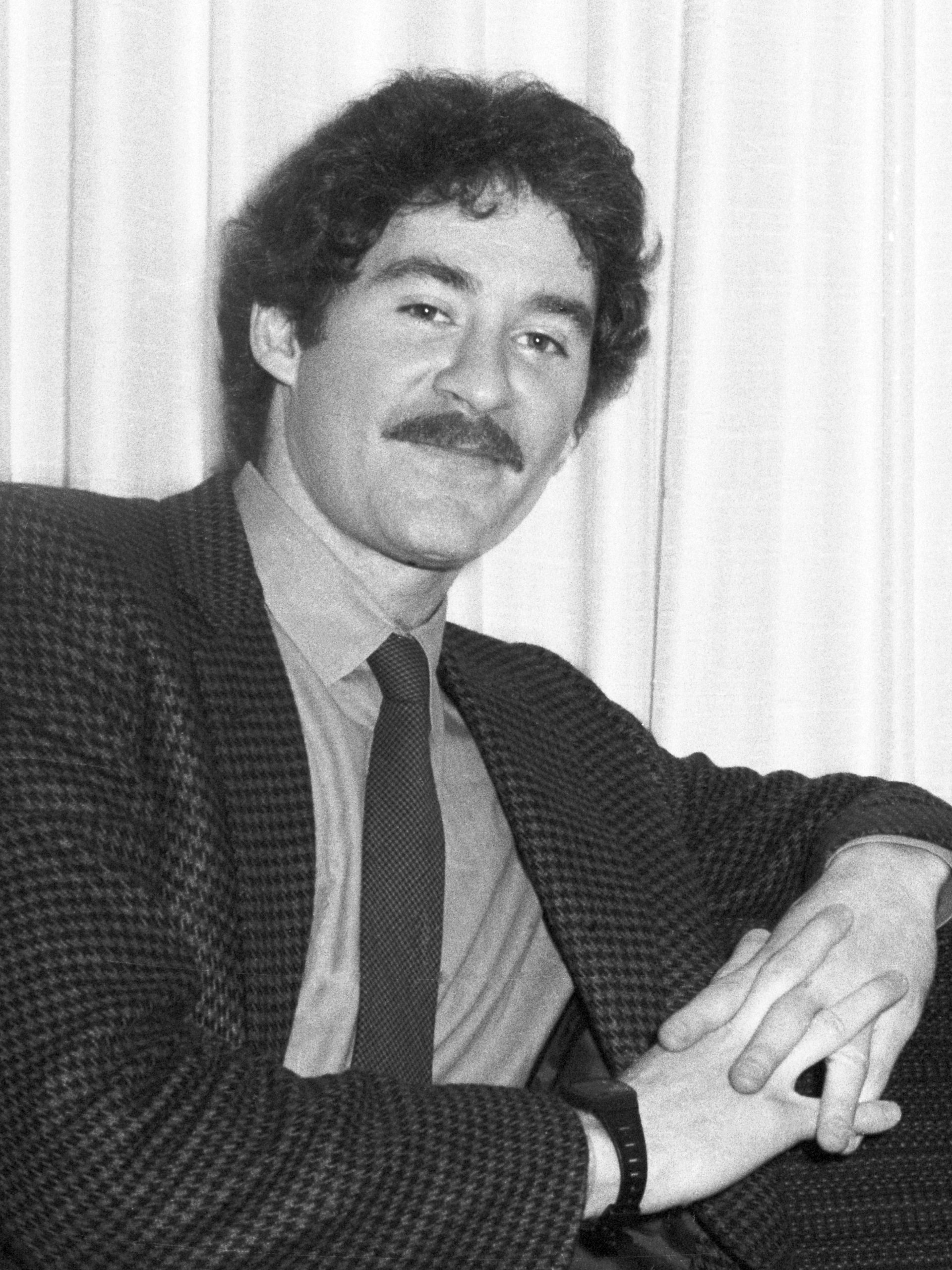

Kevin Kline, 1987, on Apartheid – Out of the Archives

Kevin Kline, a five times Golden Globe nominee is costarring with Sigourney Weaver in The Good House.

In 1987 Kline spoke about apartheid in South Africa, during an exclusive interview with the journalists of the Hollywood Foreign Press about the movie Cry Freedom directed by Richard Attenborough, costarring Denzel Washington.

Kline, who portrayed Donald Woods in Cry Freedom, talked about meeting the journalist and anti-apartheid activist in preparation for the role: “I connected with Donald immediately, he’s one of the most open, generous, accessible people I’ve ever met. When I first spent an evening with him, we talked well into the night, sitting around his kitchen table, with his wife Wendy and a few of their kids who were in town at the time. The whole family was terribly gracious, so I felt quite at ease and I connected with him. I agreed with his politics, and I certainly admired his courage, I identified with him more than I felt that I was similar to him.”

The actor learned about the issue of apartheid in South Africa in a personal way from reading the screenplay and meeting Woods’ family: “I felt much more informed, obviously, from the first time I read the script. What I loved about the script was not only that it was an inherently dramatic, gripping story, but the fact that the information and the insight that I got from it about what the situation was in South Africa was brought home to me in a much more empathic, human way. It wasn’t just facts and data I was reading in a journalistic account. I related to this middle-class, well-heeled family and felt for the first time as an American that I could understand that situation because I could identify with what it was like to live in South Africa through the Woods family, and what happened to them really brought it home, rather than it being dispassionate and statistical. I felt shocked and appalled and I felt that the story had to be told, had to be heard.”

Kline also learned about Steve Biko, leader of the Black Consciousness Movement, that Woods supported with articles in his newspaper, the Daily Dispatch: “It was clear from the way the script was laid out that this was not a deep psychological exploration of any one character, but it was really a big, epic scaled story tracing these two families, the Woods’ family and the Biko family. So the more I got to know Donald and the more of his books I read, the more insight I got, and the more Donald Woods is educated through his friendship with Steve Biko and what happens to him with the police and with the government, as he becomes more and more aware and less naive, so did I. I just kept wanting to know more, so the inherent dramaticness of the story was always there.”

The actor confirmed that he talked to his co-star Denzel Washington, who played Steve Biko, about the parallels between racism in South Africa and in Hollywood: “Yes, we talked about it, and our relationship was great. Denzel is a charming man, warm and very funny, he’s got a wonderful sense of humor, so we laughed a lot. He was also the only other American on the set; not that the two of us went off and talked about the Mets and the Giants or something like that, because I’m not a baseball fan, but we talked about New York and the theatre, so we got to know each other as friends. And we certainly talked about the situation here, about what it was like being a Black actor in Hollywood, the problems of that, the stereotyping and the paucity of really good roles for a Black actor. It was clear what the parallels were between the civil rights movement in the sixties and slavery a hundred years ago.”

Kline felt transformed by what he learned about South Africa from making the movie Cry Freedom, as he hoped audiences would be: “The movie changed me, it left me with a feeling of shock and horror so that I could no longer be complacent about the situation in South Africa, sit back and think, ‘It’s a terrible situation but, of course, I can have no effect. There’s nothing I can do to change it. It’s all up to the governments and I just hope they work it out.’ There’s something inspirational in what Donald Woods does that gives us all the feeling that, however impotent we might feel, we have to do something, whatever we can, whether it’s writing a letter to our congressman or standing up and being heard or taking a stand when the time comes. And it may be overly idealistic of me, but I would hope that the whole world would feel moved by our movie to exert pressure on South Africa to hasten the dismantling of apartheid, bring them to the negotiating table so that a bloodbath, which seems inevitable, can be avoided.”

These are the steps Kline took in 1987 to oppose apartheid, that would not come to an end in South Africa until 1994, partly due to international pressure: “I haven’t done anything on a grand scale at all, but I’ve made sure that all of the businesses I do business with, like my bank, have divested their interests in South Africa. My consciousness was raised, I suddenly became aware that I had to take responsibility for those things. My publicness as an actor is such that I try to limit my public exposure to my acting, I’m loathed to take a public position on politics, I’m not a political speaker. I obviously endorse the political stance of the film and I’m making a statement that way, but I’m certainly not saying that that’s enough. I will do what I can on a private level, in terms of sending money for support or writing letters to my congressman and pushing for economic sanctions; but, more than anything, my interest has been piqued, my need for more knowledge has increased, and now I’m pursuing more information.”

Kline concluded by denouncing racism everywhere, not just in South Africa: “The movie is specifically about South Africa, but it’s obviously about racism and bigotry and injustice, about man’s inhumanity to man and the sins of the world, so it is a universal theme. And I know that the situation in South Africa is not black and white, literally, there’s a lot of grey areas. It’s a political question, it’s not merely a racial question, and I’m aware that it’s very complicated, I don’t think there are just heroes and just villains, but there are people who don’t think they’re doing this, but who lose sight of the fact that what they’re doing is fundamentally an aberration. It’s a terrible sin against their own humanity.”