- Industry

The “Light & Magic” of the House that George Lucas Built

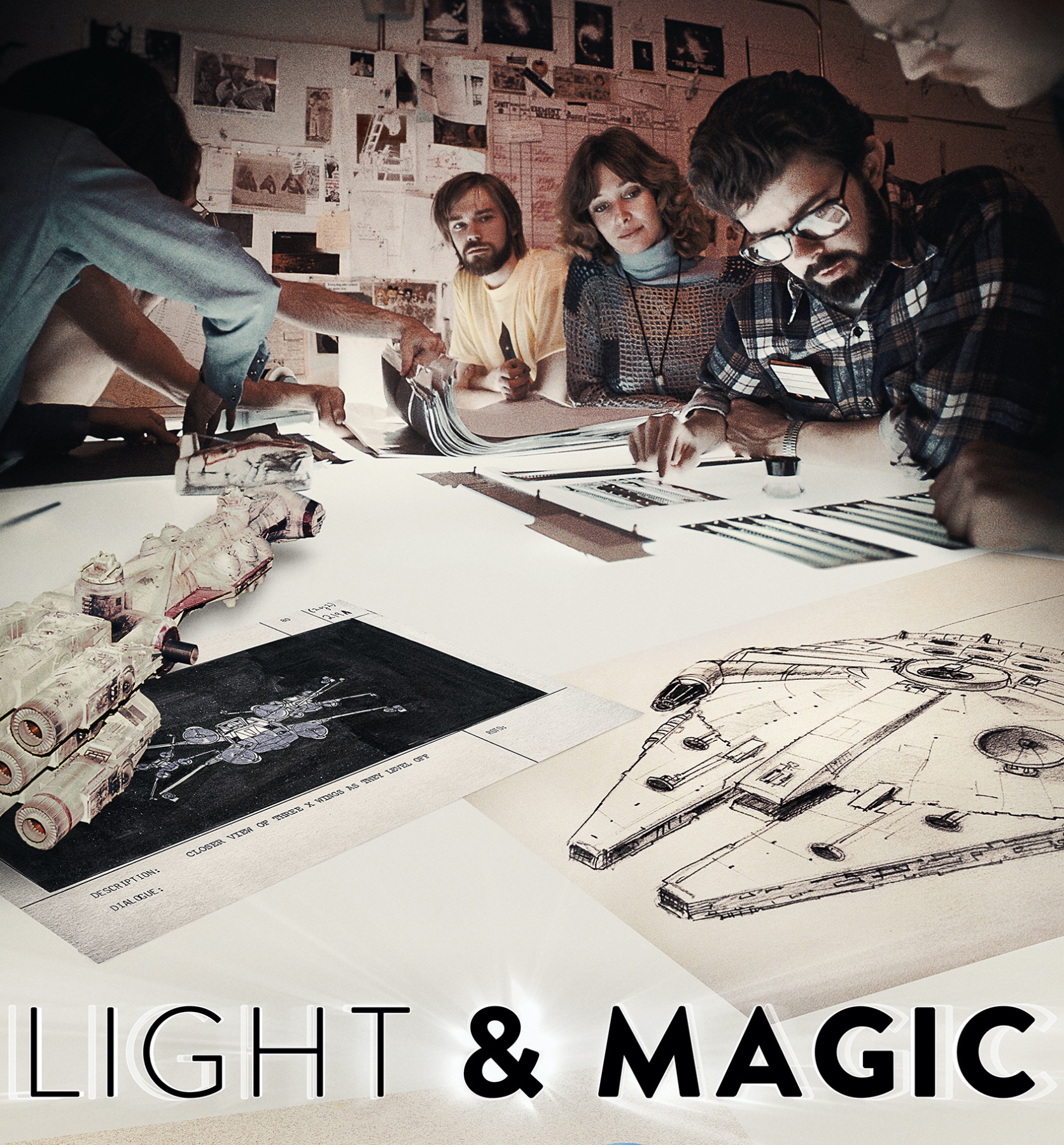

The visual effects house Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), founded by director and producer George Lucas in 1975, celebrates 45 years since the world learned of its existence when Star Wars: Episode IV- A New Hope (1977) was released, with that sequence of the Star Destroyer flying across the screen, heading to infinity.

Since then, ILM has not stopped pointing to a future full of promises to discover, as well as challenges and secrets to reveal.

Through six one-hour episodes, the mini-documentary series Light & Magic (2022), which premiered last week on Disney+, is a journey through time since Lucas recruited his team of artists in 1975 to form ILM.

Lucas, upon learning that 20th Century Fox’s in-house effects division was shut down, realized that in Hollywood, there was no company that could bring his Star Wars universe to life.

Two-time Golden Globe nominee, filmmaker Lawrence Kasdan, who wrote several of the Star Wars films, said in an interview via Zoom, “Lucasfilm is probably the best and largest archive in the history of cinema. This is because George Lucas, from the beginning, wanted to capture everything related to the behind-the-scenes of his films.”

“He stored all the background paintings of the scenes, the drawings, the models of creatures, characters, and ships. When we came to do the documentary series, this was an immense treasure ready to be opened for us. They gave us access to things that had never been seen or shared before, even in the specials of the DVD and Blu-Ray editions.”

Kasdan stumbled upon the opportunity to do Light & Magic when the documentary division of the Imagine Entertainment studio, co-founded by Golden Globe winner Ron Howard (Willow, Solo: A Star Wars Story), asked him if he was interested in a non-fiction project.

Chronicling the history of the company founded by George Lucas seemed destined for Kasdan since the director of films such as The Big Chill, Silverado, and The Accidental Tourist, started his career writing the scripts for Star Wars: Episode V-The Empire Strikes Back, Star Wars: The Return of the Jedi and Raiders of the Lost Ark, movies which were brought to life by ILM.

Kasdan said, “I had already done a documentary with my wife about a restaurant that was going to close. The Imagine documentary division asked me, ‘What do you want to do now?’

“I said, ‘How about telling the story of visual effects?’ So, they suggested I do the ILM story because they have a relationship with Disney (now owners of ILM) and Lucasfilm. I expressed my fascination for this group of artists whom I consider geniuses.”

The 73-year-old Kasdan added, “From the beginning, my goal was to make Light & Magic a documentary series about people and not about technology. Going back to those archives on film and video made me even more fascinated with this group of people who were recruited from fields outside of Hollywood and its studios, all in their early 20s, some with commercial backgrounds, while others were auto mechanics or automakers who made masks of creatures and monsters just for a hobby.”

Light & Magic puts Lucas in front of the camera to reminisce about when he founded ILM and talk about his process of recruiting the future heads of the various departments. While techniques such as stop motion animation, the use of models against blue backgrounds to be replaced with images such as planets or stars, and the application of makeup to create aliens had already been done throughout the history of cinema, Star Wars: A New Hope needed all of those techniques to take several steps forward, in addition to adding new visual effects that had not been invented in 1975.

Phil Tippett, heir to Ray Harryhausen’s stop motion technique (Jason and the Argonauts, 1963) was in charge of Star Wars in making the famous chess hologram sequence with creatures. He recalled, “Most of us graduated from doing commercials using different animation techniques but working for George Lucas at ILM was like getting a Ph.D. in visual effects.

“He was committed to giving us what we needed as artists to get things done, and with time came along filmmakers, including Steven Spielberg, who were like the great conductors of the orchestra. They were always ready to give us what we needed most.”

Among the successes of Light & Magic is that it does not fall short in revealing the problems and challenges, not only technical, but in human relations. Hollywood knows that John Dykstra, who oversaw the visual effects for Star Wars: Episode IV- A New Hope, was not invited to move with the company to Northern California.

Lawrence Kasdan gets candid statements from the creator of the Dykstra Camera and George Lucas about the moments when sparks flew and damaged their working relationship in the making of the film in 1977.

The heart of Light & Magic, as explained by Kasdan, lies in how the episodes take their time to tell the story of several of the leading artists, their relationship with the art world, and even with their parents and wives. In a poignant moment, Tippet tells the camera that he found out as an adult that he was bipolar, and that animating his dummies was always a kind of therapy for him, and that without it, he might have taken his own life.

In addition to Lucas and ILM’s team of artists like Tippett and nine-time Oscar winner Dennis Muren, Kasdan also enlisted filmmakers like Golden Globe winners Steven Spielberg, Ron Howard, James Cameron, and Robert Zemeckis to be a part of the narrative of the documentary series, recounting the challenges of their films, as well as pointing to the ingenuity of the people who work at ILM.

Kasdan pointed out that his miniseries can attract the attention of even those who do not want to make movies but are looking for great examples of leadership and teamwork.

He said, “The experience of editing these six hours of the series was very exciting. Returning to that atmosphere and enthusiasm, which only ILM had, was something unique and special. This collaboration between geniuses is amazing.

“They competed with each other with their ideas. They worked very hard. But basically, they turned to their friends, complicit comrades, and asked, how are we going to solve this problem? How are we going to do this? This is the problem that we face today.

“They worked these things out in a community, one where all these people took care of each other. All of this seemed to me the most attractive thing that we dealt with in Light & Magic.”

As a company five years shy of its half-century milestone, ILM had to make the leap from the analog to the digital world. Light & Magic becomes a testimony to the vision of its founder George Lucas, who, from the beginning, was desperate about the limitations of the world of machines and not for the “ones” and “zeros” that allowed fewer restrictions. Lucas’ image and sound editing systems also show the evolution of Kasdan’s output, as well as the brief time that Pixar was created under one roof.

Phil Tippett recalled with a smile and a hint of regret (but now, owns his studio in which he also pioneered the leap into the digital age), “For me, the entry of digital was something devastating. I even got pneumonia while working around 1992. ILM had approached me via Denis Muren to ask me, ‘How could a creature be created in a computer? To breathe and feel alive on screen?’

“Later, when we had already assembled a whole team to experiment with stop motion and make the dinosaurs for Jurassic Park (1992), a couple of pioneering animators showed Spielberg the skeleton of a walking T-Rex, which made him immediately take notice and decided to make the animals by computer animation.

“Steven, who has always been a very empathetic guy, came up to me a few days later and asked me, ‘How do you feel about this? Because it must be something monumental for you.’ I told him, ‘I feel outdated.’ To which he replied, ‘That is a great phrase! I’m going to use it in the movie.’ He was able to get something good out of my depression.”

Leaving its own mark in the era of fantastic filmmakers, ILM at the same time evolved with the so-called invisible effects achieved in films such as Saving Private Ryan, Forrest Gump, The Revenant, and even in the experience of virtual reality, Carne y Arena (Flesh and Sand), directed by Golden Globe winner Alejandro G. Iñárritu.

“I never had a problem sharing how we did things because I know how hard it was to get there. I always liked knowing that I could make someone happy by knowing how we made an effect. Especially if that can inspire them to take it to another level,” concluded Muren, who is wishing, along with Tippett and Kasdan, that Light & Magic will be a meeting point for those who will be the new magicians of cinema.

Translated by Mario Amaya