- Golden Globe Awards

Loveless (Russia)

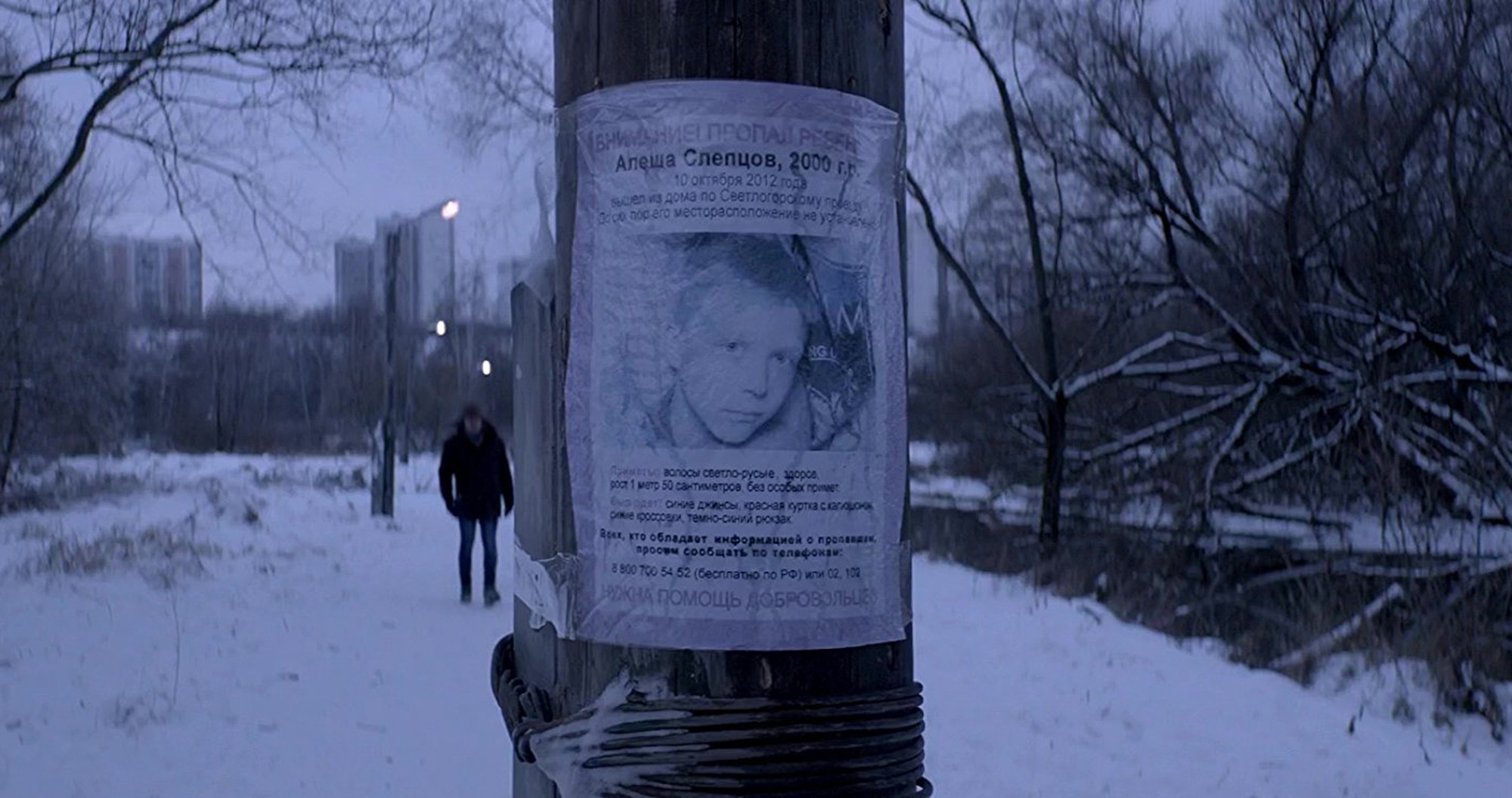

Zhenya (Marina Spivak) and Boris (Alexey Rozin) can’t wait for their divorce to be finalized. They have already moved on, looking forward to their future lives, each with a new partner. As for their 12-year-old son Alyosha, he is not part of either’s equation and seen as a burden. After witnessing another of their angry fights, the boy disappears, vanishing without a trace from the Moscow neighborhood where the family lives. A search is organized. The police are involved but don’t really care. A bunch of well-organized volunteers take over. All the while the parents still bitterly argue, their mutual resentment, frustrations and recriminations escalating. No grief though, just the panic and annoyance that the crisis might jeopardize their plans.Winner of the Jury Prize at the last Cannes Film Festival, Loveless is Andreï Zviagintsev’s fifth movie since his first opus, The Return in 2003. A Best Foreign Language Film Golden Globe winner with Leviathan in 2015, he is certainly, at 53, the most famous Russian filmmaker of his generation – and also one of the most controversial. He has been highly criticized and lauded for his no holds barred portrayal of his country and Putin’s politics.The idea for Loveless came after he failed to secure the rights of a remake of Ingmar Bergman’s 1973 Scenes From a Marriage. Still, he wanted to show the breakdown of family life but within a specific time frame of post-modern and post-industrial contemporary Russia. “The movie starts on October 9, 2012 and ends on February 1, 2015 when we are in the midst of the Ukrainian war”, he explains. “And during these 30 months, Russian society has changed a lot. People still had hope for change and some spirit of freedom in 2012 and three years later there was apathy and lack of understanding of the perspective we had.”Zviagintsev also insists that the theme of Loveless is universal, like the aridity of love he has often depicted. “The problem of lack of love, of people being distant from one another, it exists in Russia but no more than anywhere else.”The film is an unflattering and chilling portrait of a Russian political class beset by wheeling and dealing and corruption, where Instagram and selfie-obsessed individuals are unwilling to examine their own flaws, living in a bubble of vapid narcissism. Many had strong reactions to the attitude of the parents, their apparent detachment, coldness and lack of empathy. “Of course they provoke negative emotions”, he admits, “but they are absolutely normal people. They are not monsters. They are unhappy human beings dreaming of happiness, dreaming of changing the obligations that keep them in a place they feel stuck in. They make it possible for the viewer to look deep inside the soul of a person, all their hidden fears, problems, and challenges. And their souls are like a battlefield.” No doubt that for Zviagintsev, cinema remains also one worth fighting for now more than ever.