- Industry

Milos Forman, Three-Time Golden Globe Winner, 1932-2018

Of several European directors who parlayed their success in Europe after the Second World War into a Hollywood career, Forman was arguably the most prominent, successful and consistent. His signature early Czech movie, Loves of a Blonde (1967) was nominated for Best Foreign Language Motion Picture by both the Hollywood Foreign Press Association and the Academy of Motion Pictures. Later, his work in Hollywood earned him four Golden Globe nominations and three wins, during a career that spanned half a century.

Born in Czechoslovakia in 1932, young Milos’ life was shaped by the war. Aged seven, he saw the Gestapo arrest his father, a member of the resistance. Three years later they took away his mother from their home.“My mother came and looked at me with terror in her eyes. I knew it was the Gestapo. And then she was gone. The house was silent. I was alone,” he recalled. Both parents were later murdered in concentration camps. ‘My parents were real patriots…(Only) much later, far from my homeland and its culture…I realized I share this strong affection for my country with them,’ Forman wrote in his biography.

A childhood fascination with the theater led him to study direction at the Prague Film Academy. He directed biting social satires that were part of the Czech New Wave and won him acclaim abroad. The Firemen’s Ball (1967), using mostly non-actors, skewered the Communist regime’s pervasive corruption, and was promptly banned. Forman went to France looking for financing, and when the Warsaw Pact troops invaded his home country to crush the Prague Spring uprising, Forman went from Paris to exile in New York and settled in Greenwich Village’s Chelsea Hotel, living on a dollar a day.

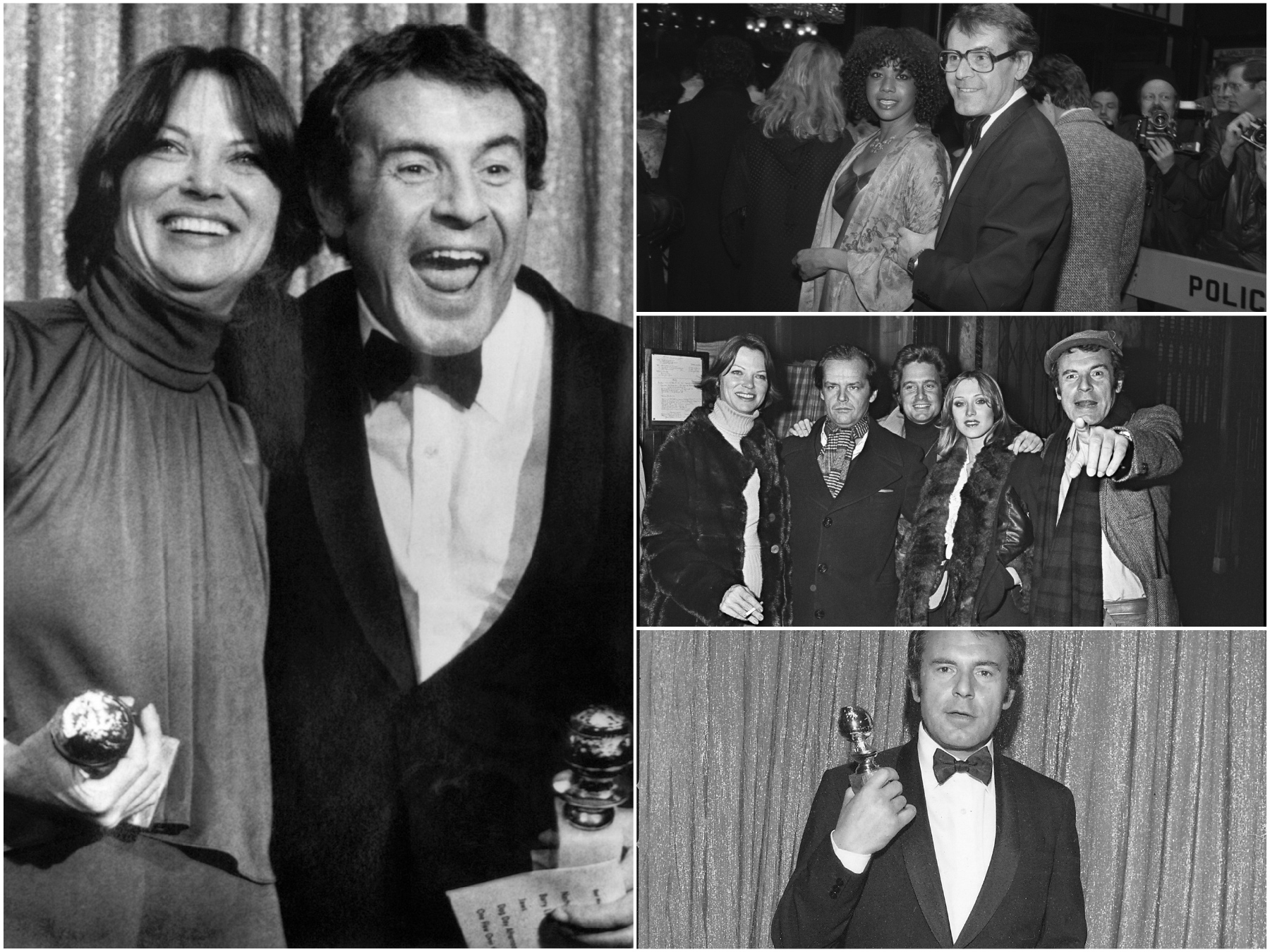

(Main photo): Milos Forman and Louise Fletcher after winning their Golden Globes for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 1976; (from the top) with actress Cheryl Barnes, one of the stars of Hair, at the New York premiere in 1979; with Jack Nicholson, his friend Winnie Hollman, Louise Fletcher and Cuckoo producer Michael Douglas in Paris for the European premiere; Forman with his Best Director Golden Globe for Cuckoo’s Nest.

hfpa archives/ getty images

Forman’s first American movie, Taking Off (1971) caught the zeitgeist. Set in his new home, New York, the comedy dealt with runaway kids, liberated parents, youth revolt, hippies and pot. It was well received abroad (six BAFTA nominations, a Grand Jury and Palme d’Or nominations in Cannes), but flopped in the US. Forman again used mostly non-actors. “My instincts were too Czech. In any case, I had to change my working style,” Forman said.

His very next outing, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) was an almost unprecedented success. It won the top five awards (film, director, script, actor, and actress) at both the Globes and the Oscars (the second movie ever to achieve that). It gathered 48 nominations and won 35 awards worldwide, anchored by Jack Nicholson’s performance, which earned the actor the second of his seven Golden Globes (so far).

Forman later said that friends had discouraged him from going anywhere near the script based on Ken Kesey’s novel, which they deemed too American for a recent immigrant. But Forman saw the opposite. Receiving the Directors Guild of America’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 2013 he said: “To me, it was not just literature but real life, the life I lived in Czechoslovakia…The Communist Party was my Nurse Ratched, telling me what I could and could not do, what I was or was not allowed to say; where I was and was not allowed to go; even who I was and was not.’

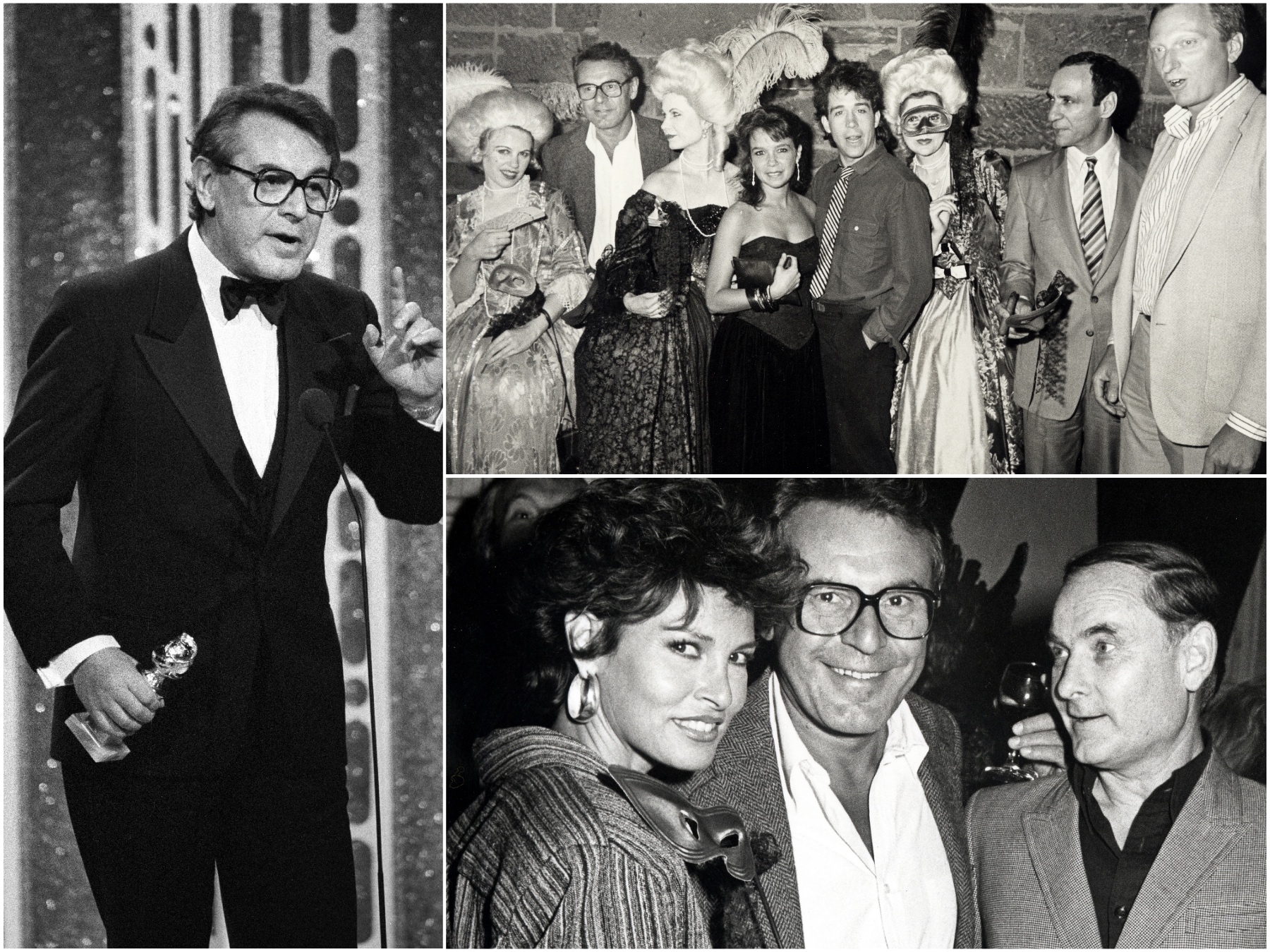

Main photo: Forman receives his second Golden Globe – for Amadeus, 1985; (from top) with the cast of Amadeus at the New York premiere, and with Raquel Welch and a friend at the after-party, 1984.

hfpa archives/getty images

Forman went on to tackle some of the most American of subjects: Hair (1979), based on the popular hippie Broadway musical, received two Golden Globes nominations; Ragtime (1981), set in New York City in the early 1900s, garnered seven Golden Globe nominations. He also tackled two quintessential American biopics: The People vs Larry Flynt (1996), a drama about the founder of Hustler Magazine that dealt with First Amendment issues, collected five Globe nominations and won Forman his third directing Globe; and Man on the Moon (1999), which attempted to distill the tormented creativity of actor Andy Kaufman, as portrayed by Jim Carrey, earning him his second Golden Globe.

Forman’s second most successful movie was a departure from Hollywood: he filmed Amadeus (1984) back in Czechoslovakia. A biopic of composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, it collected six Globe nominations and four wins, including Direction and Best Motion Picture-Drama. Forman discovered the Peter Schaffer play in London, and it appealed to his sense of irony: “I was used to seeing the Russian and Czech films about composers, and they were the most boring films,” he said in an interview. “Communists love to make films about composers because composers compose music and don’t talk subversive things.’Handing Forman his award, DGA’s past president Taylor Hackford said: ‘No matter what subject or genre he tackles, Milos finds the universality of the human experience in every story, allowing us — his rapt audience — to recognize ourselves within the struggle for free expression and self-determination that Milos so aptly portrays on the silver screen.’

He last spoke to the Hollywood Foreign Press for the release of Man on the Moon, explaining his preference for bittersweet comedies. “My first big love was films by Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, so I am trying to do the same. If you don’t want to be silly, you have to, as far as you go in the comedy, (…) you have to go in the other direction, is the tragedy or drama to keep it in equilibrium. (…) I just love movies which make you laugh and cry and still feel intelligent. That’s what really excites me – to see such a film.’

(Clockwise from top left): with his Salieri, F. Murray Abraham, at the Directors Guild Honors, 2008; with Courtney Love, star of The People vs. Larry Flynt, at the premiere, 1996; with his Golden Globe for Best Director for Larry Flynt, 1997; presenting One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest at the Bryant Park Film Festival, 2011.

hfpa archives/ getty images

Joining the ranks of great European expat directors he always maintained a healthy dose of irony vis-a-vis his adopted cinematic homeland, telling the HFPA: “I realize that in Hollywood I have to learn golf and tennis and English. (English) is not so important. Golf and tennis are important. No, no, no I am not putting down Hollywood. Hollywood is a wonderful thing. (…) The problem is that people think Hollywood is Hollywood. No -Hollywood is a thousand Hollywoods. Behind every door, you find a different Hollywood and the question is if the right person finds the right door. If he doesn’t then Hollywood is the worst place to make movies. If you do find the right door, its the best place in the world to make movies.”

As the motto for his website, Forman posted this:’Everything I did in my life I did because I wanted to win… However, winning is quite exhausting, so the next thing…. is this: Fine, I have won, but that ’s not it. Next time it’s going to be even harder.’

Sadly, there will be no next time for Milos Forman, director extraordinaire, subversive artist, frequent winner, dead at 86.