- Industry

Moviegoing Memories in the Philippines’ Eternal Summer

Imagine one of my childhood movie-watching experiences when I was a kid growing up in Calasiao, in the province of Pangasinan, Philippines: It is nighttime in a grassy open area beside the town’s church, built in 1588. A projector shows Elvis Presley’s Blue Hawaii on a screen mounted atop a truck.

In the dark, people stand in front of the screen, watching the blue-eyed singer-actor in a story and setting that are so far removed from our lives.

I eat boiled peanuts from an old newspaper page folded like a cone, bought from a woman peddling those nuts. Light from a kerosene lamp gives the vendor a soft golden glow.

The free movie showing was announced days earlier by a roving truck owned by The Coca-Cola Company, which has a bottling plant in my town and offers these film treats as a gesture of goodwill. It’s on the same truck that, later, the movie screen is mounted.

A world-famous American soda brand showing a Hollywood movie beside a centuries-old church built by the Spanish says it all about how my love for cinema came about. A late great novelist, Nick Joaquin, summed up the Filipino psyche best – the result of being colonized by Spain and then the United States: “400 years in the convent and 50 years in Hollywood.”

After the churches, the movie palaces arrived. In the Philippines, where the weather is virtually like summer year-round, the air-conditioned film theaters offer not only an escape from poverty and daily realities but also an oasis of coolness away from the relentless heat and humidity.

In Dagupan, the city next to my town — which had several movie houses, some rickety with rats scurrying under my feet, others newer and more comfortable – a female relative who helped raise me (not a nanny because we were not rich) took me to, mostly, Filipino movies. My Atchi Viring and I took the jeepney to the movies on weekends. During summer vacations we went any day of the week.

We watched commercial movies – musicals, action flicks, dramas, and slapstick comedies – churned out by the local studios. That’s right, back then the Philippines had many cherished movie studios, just like Hollywood.

When I entered high school, I went to Dagupan on my own and often snuck into films rated for adults only. That was how I first saw Don Johnson on the screen.

IMDb’s description of Leonard J. Horn’s The Magic Garden of Stanley Sweetheart explains succinctly that what I watched was R-rated: “The movie is about 23-year-old Columbia University dropout (Stanley Sweetheart, played by Johnson) who seeks his identity during the sexual revolution.”

With my heart thumping as I nervously paid for my ticket, not sure if the box office clerk would allow an obviously underaged me inside, I somehow got in. Ticket sales matter everywhere, obviously. That’s how I saw my first Michelangelo Antonioni film, Zabriskie Point.

But the art of cinema was not on this raging adolescent’s mind. I also managed to sneak into another adult-only movie, Ted Post’s The Harrad Experiment. Don Johnson was, again, the protagonist. He seemed to be, clearly, the casting favorite for the types of movies that explored the sexual revolution of the era. Here’s part of IMDb’s story summary of The Harrad Experiment: “At Harrad College, where controversial coed living situations are established, the students are forced to confront their sexuality in ways that society previously shunned.”

Carried by a seductive crescendo, the description goes on: “Part of the experiment is to pair incompatible members of the opposite sex as roommates in order to make them shun the traditional concept of monogamy…In charge of the ‘experiment’ are Prof. Philip and his wife, Margaret, who seem to enjoy the tension they instigate, as well as the graphic sexual episodes that unfold.”

As a child I was, needless to say, exposed to kiddie staples like Robert Wise’s The Sound of Music and Robert Stevenson’s Mary Poppins. When my family visited the big capital city, Manila, we saw these family classics in some very impressive movie palaces. This happened over, mostly, the long summer breaks.

It was not unusual, during those times, for my dad to take the family to the movies. That’s how we got to see Cecil B. deMille’s The Ten Commandments (with Charlton Heston and Yul Brynner) and David Lean’s The Bridge on the River Kwai (starring William Holden, Alec Guinness, and Sessue Hayakawa).

A favorite family anecdote is that, at one point during the screening of The Bridge on the River Kwai, they noticed I was missing. After a few frantic minutes, they found me hiding on the floor, too terrified by Lean’s realistic depiction of the war drama set in occupied Burma.

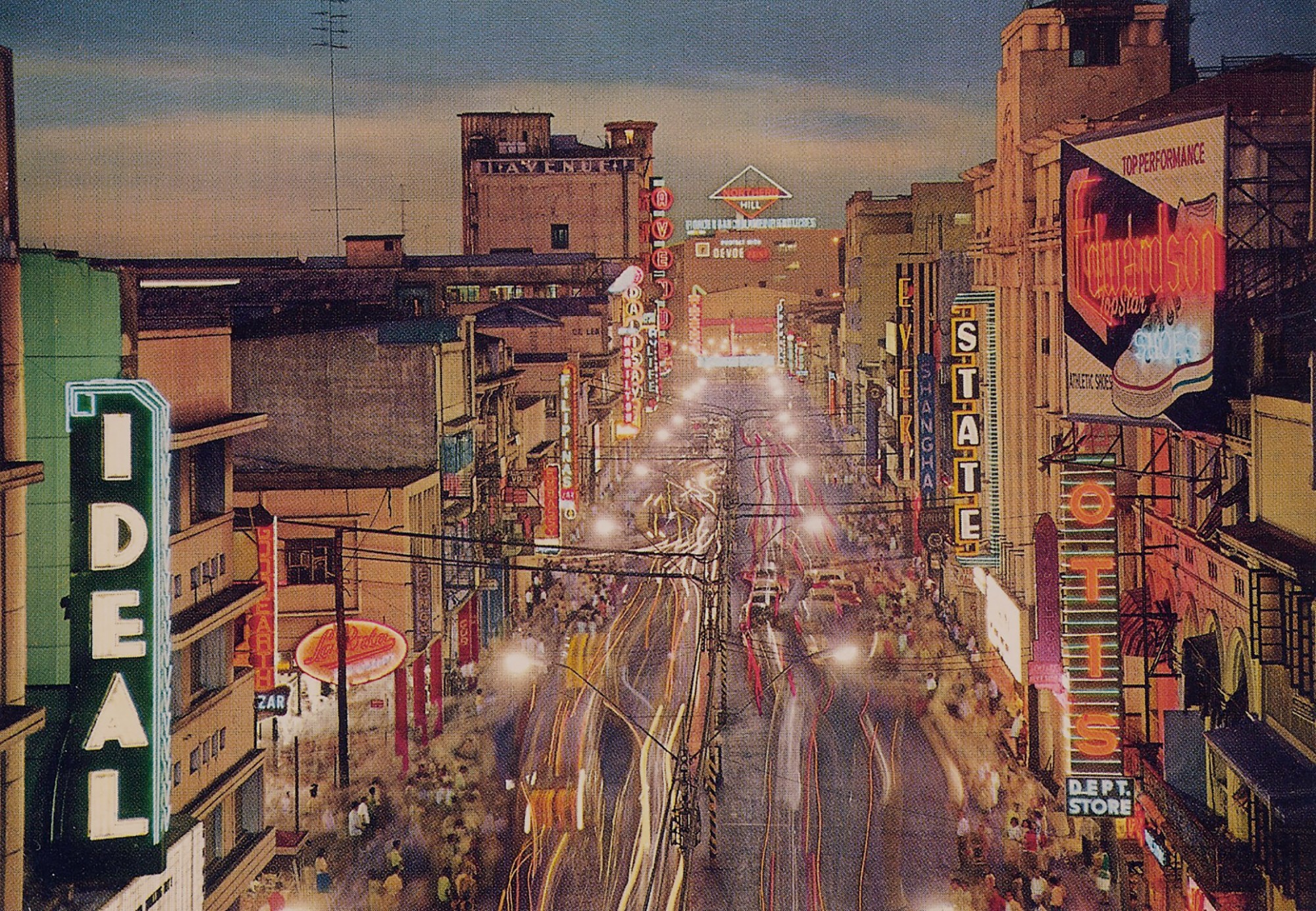

Even as a kid, the grandeur of these old film palaces that lined Rizal Avenue, an old thoroughfare in Manila popularly known as Avenida, was not lost on me. I still remember the wonderful smell of these theaters and the luxurious feeling of being inside an air-conditioned building – a respite, however brief, from the tropical humidity outside.

To this day I still remember the majesty of Manila’s movie theaters like Ever, Ideal, and Odeon. Sadly, like most movie palaces around the world, these too have been demolished or are left decaying, now virtually unrecognizable and turned into seedy stores.

In college, I first discovered Martin Scorsese through his “little” film, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. That’s when I first became aware of Ellen Burstyn. It’s ironic that, back then, I recall critics dishing films being made as very corporate-minded or too studio-centric.

But, today, look at some of the films produced in that era and which I saw in Manila. Look at Coppola’s The Godfather I and II

I saw whatever European films I could reach, mostly through screenings by Goethe-Institut Philippines.

My university days also coincided with the second golden age of Philippine cinema. I lapped up those that would become classics: Lino Brocka’s Insiang, Tinimbang Ka Ngunit Kulang and Maynila: Sa Mga Kuko ng Liwanag, Ishmael Bernal’s Nunal sa Tubig, Behn Cervantes’ Sakada, Mario O’Hara’s Tatlong Taong Walang Diyos and Mike de Leon’s Itim and Kung Mangarap Ka’t Magising. And so many, many more than the ones mentioned in this short list.

To this day, being inside grand movie palaces in Los Angeles or other cities makes me nostalgic.

Just recently, when I hung out at the Village East cinema during the Tribeca Film Festival in New York, I looked up and marveled at the ornate ceiling of the 1920s Moorish Revival-style theater. Instantly, the sight transported me back to my summer movie afternoons inside Manila’s old film palaces. Right next to me I saw a little boy hiding under the seats, convinced that the drama projected on screen was really happening.