- Golden Globe Awards

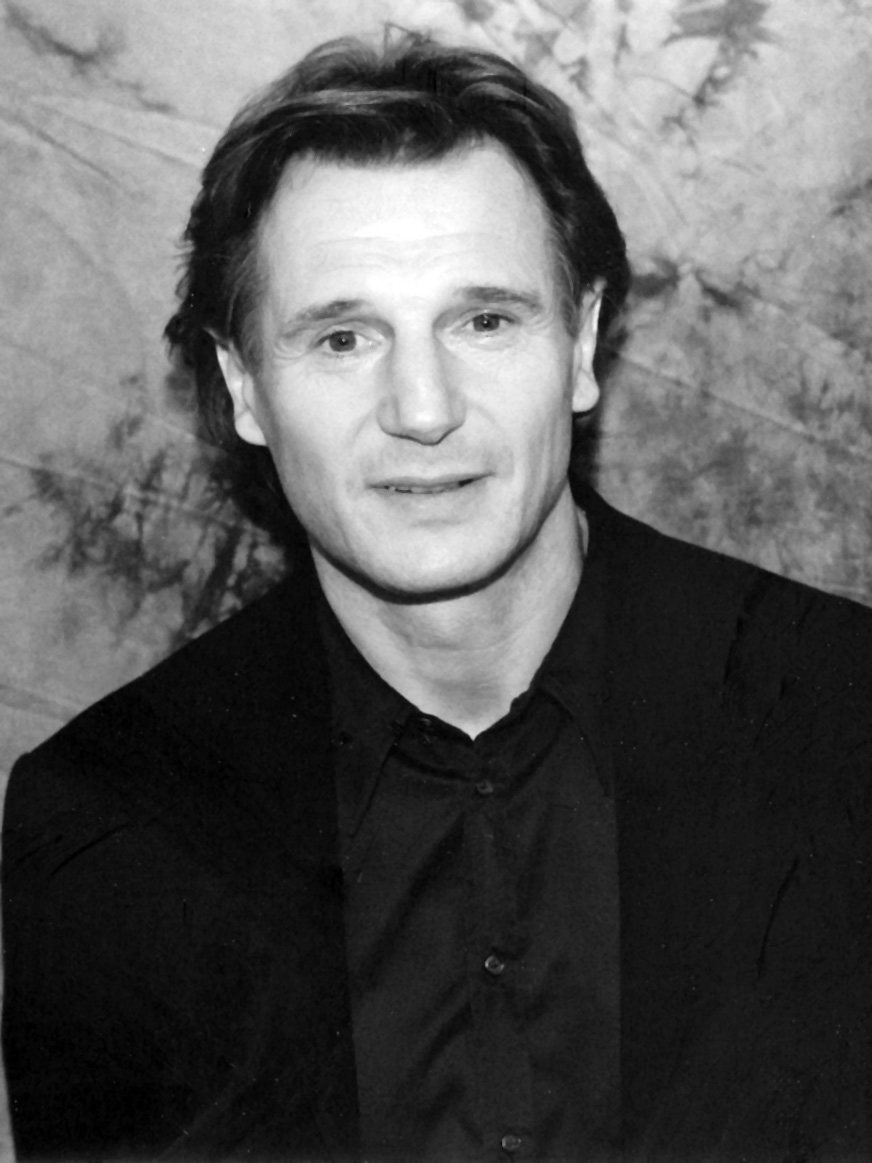

Out of the Archives, 1996: Liam Neeson on Ireland and “Michael Collins”

Liam Neeson, three- a timeGolden Globe nominee as Best Actor – for Schindler’s List (1993) directed by Steven Spielberg, Michael Collins (1995), and Kinsey (2004) written and directed by Bill Condon – spoke with the journalists of the Hollywood Foreign Press in 1996 about portraying the hero of Irish independence in Michael Collins, written and directed by Neil Jordan.

Neeson, born in Ballymena, Northern Ireland, said he had heard about Michael Collins as a child when visiting his grandparents on the southeast coast of Ireland: “My history with Michael Collins is steeped in an early childhood memory of being in my grandparents’ house in Waterford in the Republic of Ireland and sometimes being ostracized by other children because I was from the Black North. I was eight or nine years of age and kids were shouting at me, ‘You follow the Queen,’ and I didn’t have a clue what this meant. Then when I went indoors my grand mum would say, ‘Why are you not outside?’ and I’d be telling her, ‘The kids won’t play with me because I’m from the North.’ Then I’d hear my grandfather saying these names, ‘Michael Collins. Èamon de Valera.” But my grandmother and grandfather wouldn’t discuss it, it would be something that wasn’t to be talked about; actually, a little bit like the Holocaust.”

He later learned about the history of Ireland in school, then read biographies of Michael Collins to prepare for playing him in the film: “It was only when I was 18 or 19 and I started learning Irish history for myself that I came across these names, and I remembered hearing about these guys from my grandfather. So that started my personal introduction to Michael Collins. Then, when Neil Jordan approached me 12 years ago to do this film with him, I started to really get into the guy, not from history books but from a number of biographies on the man written by people who actually knew him and lived back in those days. There’s a fantastic one from 1937, “The Big Fellow” by Frank O’Connor, who was one of Ireland’s great short story writers, and that became my bible. It’s historically accurate but it reads like a novel and I always had that book with me; it was very easy to delve into for real quick research before you even did a scene. Michael Collins is a huge hero of mine. I read a lot of biographies and he literally leaped out of the page at me, he seemed so alive, and his spirit was so intense.”

Collins has been called ‘the father of modern terrorism’ for his tactics in fighting against the British during the Irish War of Independence (1919 to 1921), but Neeson disagreed: “For a start, Michael Collins to my mind was not a terrorist; a terrorist is someone who puts bombs in restaurants and blows up innocent people, but he did not do that. Our film is about a period in Irish history, but it’s also the story of every country that has wanted to shed the yoke of oppression, especially America. In fact, there are lots of similarities between George Washington and Michael Collins, both holding together and running a rag-tag army that developed hit-and-run tactics. He was inspired by George Washington, as well as by Lawrence of Arabia (who fought for Arab independence during the First World War) and by the Boers fighting the British at the turn of the century in South Africa. This kind of fight is always in our history, and in Ireland, it has remained dark and murky, never to be talked about, so it’s time to air that, and there’s no better way than a feature film.”

These are some of the reasons why, according to Neeson, Michael Collins remained a controversial figure, canceled from Irish history, “It’s because the 1921 Anglo-Irish treaty culminated in the Irish Civil War (1922-1923), that literally wrenched families asunder in Ireland, mother against son, father against son, brother against brother, and it’s still felt to this day. Harry Boland (Aidan Quinn) and the rest of the irregulars, the people who didn’t support the treaty, were astounded because they knew Collins not to be a compromiser. And it’s a measure of how people viewed the great Michael Collins when he came back, that this superman actually compromised; so it’s the backhanded tribute to the man. But he had to compromise because he was there in London facing the crème de la crème of British politicians. There has never been a cabinet like these fellows: Lloyd George, Winston Churchill, Lord Birkenhead, Neville Chamberlain. And here was this 30-year-old country guy sitting there, negotiating for the first time a peace and he knew that the Irish Republic that everybody was holding out for was nowhere near the negotiating table, that it was not even going to be discussed.”

The treaty would have been only the first step toward greater independence for Ireland, said Neeson: “There actually wasn’t a lot of animosity between the two, Michael Collins and Èamon de Valera, and it’s part of the tragedy of that whole period of Irish history that my character says, “I’m not going to argue over a form of words,” because in reality what it boiled down to Collins’ compromise was that they were arguing over a sentence in this treaty, it literally was 3 or 4 words. It was the refusal of de Valera and his comrades and cohorts to see this as a steppingstone, that caused the split. But Collins was not going to rest there, he was going to implement the treaty, bring peace to Ireland because he knew that people had had enough of warfare, and once that peace was stabilized and the British Army moved out, the Irish were going to be able to run their own country as a free state. Then from there, they would start planning the next phase, and it was part of the tragedy that de Valera refused to see that.”

Neeson speculated that Ireland would have developed into a very different country if Michael Collins has not been murdered in 1922: “Collins was a realist, he did not want to coerce the Protestants in Ulster, Northern Ireland, into a united Ireland, but he did want a united Ireland for nationalistic and economic reasons. That was Collins’ great genius; the man was a brilliant organizer and Finance Minister, he had incredible plans for all of Ireland, economically, socially, culturally, to put it on the map, to barter and trade with every nation in the world that wanted to. That was his ultimate goal. Instead from 1923 onwards we got an Ireland that was conservative, Catholic, inward-looking, quite guilt-ridden and that only now seems to be blossoming, that’s fair witness to the musicians and poets and writers that have come out over the past ten years. Ireland is now kind of hip, which Collins would have loved, but I believe that he would have brought that blossoming out much earlier on.”