- Industry

Out of the Vaults: Cecil B. DeMille’s “The Cheat”, 1915

When Cecil B. DeMille released his silent movie The Cheat in 1915, his villain was a Japanese ivory merchant called Hishuru Tori played by Japanese star Sessue Hayakawa. Japanese Americans rose up in arms protesting the casting. The director simply re-released the film three years later, changing the Tori character to a Burmese, renaming him Haka Arakau, and switching the title cards. In his book “Cecil B. DeMille’s Hollywood,” author Robert Birchard writes that the change was made because there were “not enough Burmese in the country to raise a credible protest.”

It’s worth noting that The Cheat made Hayakawa a star. There were almost no Asians in Hollywood at the time and a lot of White actors were given Asian roles, so it’s interesting that deMille cast a real Asian. Despite the stereotypical character he played, Hayakawa, with his fallen angel looks, became a sex symbol for the mostly White women who made up the audience.

In the story, a pampered socialite, Edith Hardy (played by Fanny Ward) embezzles $10,000 of a charity’s money to play the stock market, loses it, and in desperation borrows the sum to replace it from the aforementioned ivory merchant, Tori/Arakau. His price is sex for the loan. When her husband (Jack Dean, Ward’s real-life husband) comes into a windfall and Edith goes to return the money, Tori/Arakau refuses to take it, demanding she sticks to their agreement. He then brands her as his property after which he assaults her in a horrifying scene. High drama ensues, and in the courtroom denouement that follows, Tori/Arakau gets his comeuppance in another horrifying scene where a racist mob comprising of the spectators rise up to lynch him, and the husband and wife walk out arm in arm, hailed as heroes.

According to Stephen Gong, the executive director of San Francisco’s Center for Asian-American Media, “It [the film] caused a sensation. The idea of the rape fantasy, forbidden fruit, all those taboos of race and sex – it made him a movie star. And his most rabid fan base was White women.” Though Japan denounced Hayakawa as a ‘national traitor’ and never released the film there, Hayakawa, undeterred, set up his own production company and earned $7,500 a week on subsequent pictures. After a fall from grace a few years later at the time of the ‘yellow peril’ paranoia, he went on to get a Best Supporting Actor Oscar nomination for 1957s The Bridge on the River Kwai.

It is useful to know that 1915 was the year D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation was released as well.

A couple of noteworthy things about the film. The poster has the following words in tiny type under the picture of Ward sitting on a bench, Hayakawa standing next to her – “The Jap’s after the bargain.” DeMille has the smallest credit of all at the bottom of the poster. And in the film, he doesn’t get directorial credit. It’s now in the public domain and can be seen on YouTube.

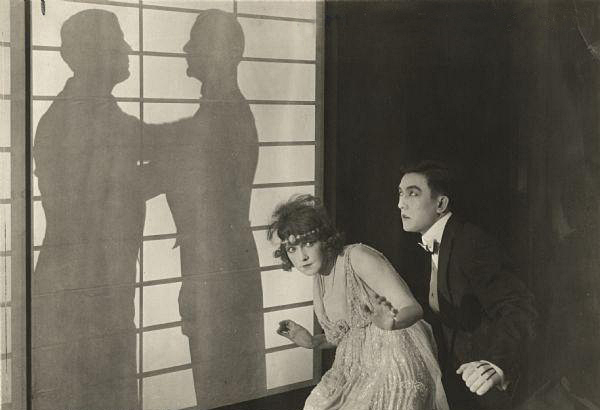

One of the things critics admire about the film is DeMille’s pioneering use of ‘Rembrandt lighting’ in an enclosed space where the lights were arranged so the actor’s face would be partly lit, partly in shadow. In his autobiography, DeMille talks of his partner Sam Goldfish’s (later Goldwyn) reaction to seeing the film where he used this technique the first time, The Warrens of Virginia.

“… a very disturbed Sam Goldfish wired me to ask what we were doing. Didn’t we know that if we showed only half an actor’s face, the exhibitors would want to only pay half the usual price for the picture? … Jesse [Lasky, producer] and I wired back to Sam that if the exhibitors did not know Rembrandt lighting when they saw it, so much for the worse for them. Sam’s reply was jubilant with relief … for Rembrandt lighting, the exhibitors would pay double!”

Hayakawa particularly benefits from this lighting, but there are other scenes with silhouettes and shadows that effectively forward the narrative as well. The camera doesn’t move much, and scenes are rapidly cut together to move the story along. There are very few intertitles. Coming in at under an hour, The Cheat cost about $17,000 to make and grossed over $140,000 worldwide, making it deMille’s most successful movie up to that time. Ward, already in her 40s (with paraffin injected into her wrinkles) provides the expressionistic acting that was prevalent in those days with much handwringing and languishing. But it is Hayakawa’s more restrained and naturalistic acting that stands out.

Despite its overt racism, when seen in the context of the times, The Cheat is an important film in DeMille’s oeuvre and was selected for preservation by the National Film Registry in 1993. It is now restored to the 1915 original version from the 1918 re-issue with funding provided by The National Endowment for the Arts, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association, and The Film Foundation. Several titles were created and others were changed based on the original continuity as part of the restoration. It was released in DVD form in 2002.

The film was remade with Pola Negri and Jack Holt in 1923, directed by George Fitzmaurice. It was again remade in 1931 with Tallulah Bankhead in the title role directed by George Abbott. In France it was remade as Forfaiture in 1937 with a few changes to the storyline, again starring Hayakawa as the Asian would-be rapist.