- Industry

Out of the Vaults: “The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog”, 1927

The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog was the 27-year-old Alfred Hitchcock’s third silent film, but the one he considered his “first true film.” It was the one that started his remarkable oeuvre of suspense films over the course of his six-decade career.

Hitchcock was influenced by the expressionistic techniques of the German directors Fritz Lang and F.W. Murnau when he was in Germany working as assistant director on The Blackguard at the Neubabelsberg Studios outside Berlin. He was also inspired by the editing techniques of Russian directors like Sergei Eisenstein. These influences show up in The Lodger. Every scene is a night scene; scenes are intercut to heighten tension; and striking visuals, lighting, and camera angles are key elements, including close-ups and overhead shots. The theme of the innocent man wrongly accused continues through several of his later films, as does his famous predilection for blondes.

The film was released in the US as The Case for Jonathan Drew, and was based on Marie Belloc Lowndes’ 1913 novel of the 1888 murders of Jack the Ripper, as well as the play “Who is He?” based on the novel as well. In the movie, the unnamed serial killer, known as The Avenger, only targets blonde women.

The first cut of the film was deemed unwatchable by C.M. Woolf, chairman of the studio Gainsborough Pictures, according to Philip Kemp writing on criterion.com. Kemp explains how producer Michael Balcon brought in filmmaker and critic Ivor Montagu to advise Hitchcock. Montagu later said, “By contrast with the work of his seniors and contemporaries, all Hitch’s special qualities stood out raw: the narrative skill, the ability to tell the story and create the tension in graphic combination, and the feeling for London scenes and characters.” Nevertheless, he suggested reshooting certain scenes, cutting down the intertitles from 300 to 80, and hiring the graphic designer Edward McNight Kauffer to design the credits and titles. Montagu is billed for “Editing and Titling” in the credits, but typical of Hitchcock’s ungenerosity, he never referred to his contributions in any interviews he did after the film was released and became a success. In a 1966 book by François Truffaut, “Le Cinéma selon Alfred Hitchcock” (updated in 1984 after Hitchcock’s death), Hitchcock told Truffaut, “The Lodger was shelved for several months, and then they decided to show it after all. They had an investment, and wanted their money back. It was shown, and acclaimed as the greatest British picture ever made.”

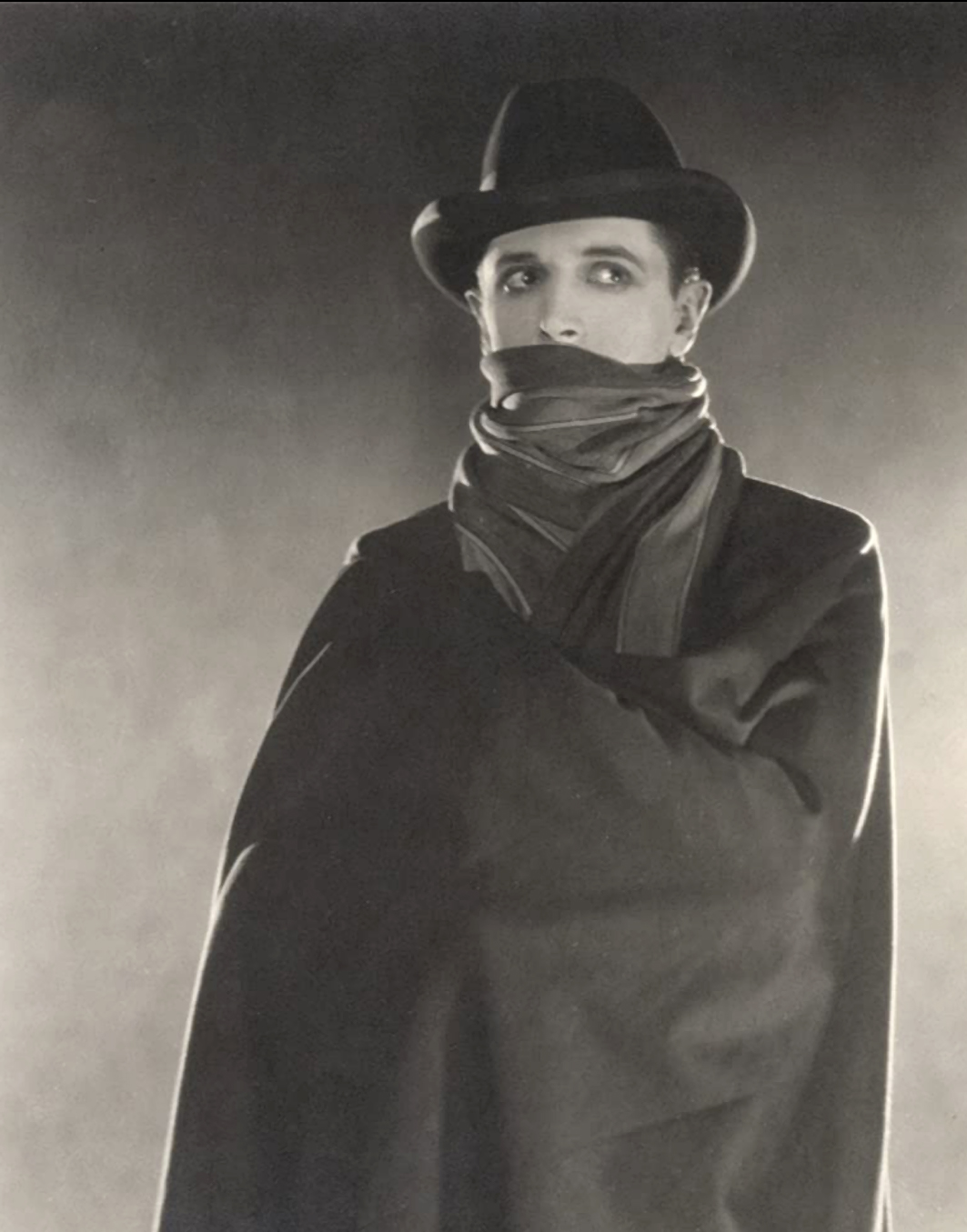

In the film, a mysterious young man (Ivor Novello) rents a room from a couple, the Buntings, played by Marie Ault and Arthur Chesney. Their blonde daughter Daisy (June Tripp, credited just as June) works as a model and has a policeman boyfriend Joe (Malcolm Keen) engaged in solving the serial murders. The lodger raises the parents’ apprehensions with his suspicious behavior – he turns all the pictures of blonde women hung in his room to face the walls, he goes out at night with a scarf swathed across his face in the manner of the killer, he points and flicks a knife at Daisy when she serves him breakfast. But Daisy is smitten with him much to their alarm and Joe’s chagrin.

With the casting of Ivor Novello, a matinee idol with much success in his previous movies, especially The Rat (1925) and The Triumph of the Rat (1926), Hitchcock was forced to change the ending of the movie from the ambiguous one of the book. Novello’s faithful fans would never allow their hero to be a sadistic villain, and the movie had to show his innocence quite clearly. In the manner of movie stars and the acting style of the day, Novello is stagy and overly theatrical in his mysteriousness, staring eyes lined with kohl, even clearly lipsticked in some scenes, glowering and posturing to appropriately menacing music. He is actually prettier than the heroine. His first appearance in the film is particularly striking, accompanied as he is by eerie music as the landlady opens the door to him with his face half-hidden by the scarf, a shadow passing behind him over the fog that is outside the door.

Some notable scenes show the fledgling director’s skill with visuals as well as his technical prowess. The film opens with a shot of the seventh victim of the serial killer, a blonde woman screaming. To film this scene, Hitchcock made the actress lie down on a sheet of glass with a light source underneath it, the camera angled downward so her blonde hair is spread in a halo of light. Another is a one where the lodger paces back and forth in his room upstairs: the Buntings in the room below stare at the swinging chandelier as the ceiling becomes transparent and they can see his agitated footsteps. Novello was filmed walking across a thick glass sheet that was superimposed by double exposure. Yet another shot has the camera over a flight of stairs looking down – through the beautifully lit scene all the viewer can see is the illuminated hand of the lodger on the banisters as he runs down several stories. And then there is the famous one of policeman Joe, head in hands looking at a footprint on the ground upon which visuals reflecting his thought process are projected.

This is the film where Hitchcock started his famous cameo roles. He appears in a newsroom with his back to the camera as he works on a reporter’s story. A second cameo is much debated by film critics. It occurs towards the end in a scene where a rabid crowd is baying for the lodger’s blood as he flees. As he manages to hang himself by his handcuffs on a fence that he attempts to climb, a group of men appears above him, of which one is speculated to be Hitchcock. Hitchcock’s wife and assistant director on the film, Alma Reville, also has a cameo appearance of her own.

Hitchcock told Truffaut the cameo “was strictly utilitarian; we had to fill the screen. Later on, it became a superstition, and eventually a gag. But by now it’s a rather troublesome gag, and I’m careful to show up in the first five minutes so as to let the people look at the rest of the movie with no further distraction.”

After a successful release of The Lodger, Hitchcock’s two previous films, The Pleasure Garden and The Mountain Eagle (now lost), hitherto held up for release by Woolf, were distributed by Gainsborough Pictures in the UK, and Hitchcock was firmly on the path to building his distinguished career.

The Lodger was remade as a talkie in 1932, again with Novello playing the title role, but it was not a success. The film was remade under the same name in 2009 with Alfred Molina, Hope Davis and Simon Baker.

Hitchcock’s version was restored by the BFI National Archive with principal restoration funding provided by The Hollywood Foreign Press Association, The Film Foundation and Simon W. Hessel. Duplicates of the only known nitrate print were scanned at 2K resolution at Deluxe. Special attention was given to recreating the tint and tone colors of the original nitrate print, using as reference the dye-tinted and toned prints made by the BFI in the 1990s. Further color correction was carried out to control contrast and therefore better reproduce the combined blue tone/amber tint sequences. A 35mm film-out color negative was created for preservation, with 35mm show prints being made for screenings. Network Releasing commissioned a new original score from composer Nitin Sawhney with the London Symphony Orchestra, which was recorded and used as the soundtrack for release prints.

The restored version can be seen on HBO Max.