- Industry

Out of the Vaults: “Pather Panchali”, 1955

At the 1992 Academy Awards, the Indian director Satyajit Ray was presented with the honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement in film. Ray was dying, filmed in his hospital bed. He could not even sit up to make his acceptance speech when Audrey Hepburn introduced him, citing the award for his “profound humanism” and “rare mastery” of the medium of film. But he was still able to joke about the fan letters he wrote to Deanna Durbin (she replied), Ginger Rogers (she didn’t), and a 12-pager to Billy Wilder after seeing Double Indemnity (he didn’t reply either), saying that all he knew about filmmaking was from watching American cinema.

The directorial debut in his remarkable oeuvre was Pather Panchali, the title translated from Bengali as Song of the Road. It was released in 1955 and became part of the Apu Trilogy, with Aparajito (1956) and Apur Sansar (1959) following. It took eight years to make and is now regarded as one of the masterworks of world cinema, the BFI listing it as one of the 100 greatest films of all time in 2020.

In 1946, Ray was working as a graphic designer in a British ad firm when he was given the 1929 novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay to illustrate. It was about a dirt-poor family barely eking out a living in a village, told through the eyes of a boy. “The book filled me with admiration,” he wrote in his memoir, My Years with Apu. “It was plainly a masterpiece and a sort of encyclopedia of life in rural Bengal. The amazingly lifelike portrayals, not just of the family but a host of other characters, the vivid details of daily existence, the warmth, the humanism, the lyricism, made the book a classic of its kind.”

French film director, Jean Renoir, on his trip to Calcutta in 1949 to shoot The River, on which Ray worked as a location scout, encouraged him to film it. Ray was already an obsessive movie buff, starting the Calcutta Film Society in 1947. His ad agency had sent him to London to work and he managed to watch 99 films in the six months he was there. The one that had the biggest influence on him was Vittorio De Sica’s neorealist film The Bicycle Thief – “[It] finally gave me an idea of how to make my own film. No stars, and mainly on location.” Nevertheless, it took Ray eight years to finish Pather Panchali.

Ray was a critic of the Bollywood film industry of the time. “All the world knew that India turned out a vast number of films with a lot of singing and dancing in them … [Bengal] didn’t make song-and-dance movies; it made tame, torpid versions of popular Bengali novels for an audience whom years of cinematic spoon-feeding had reduced to a state of unredeemable vacuity,” he told a critic. “It was high time Indian cinema came of age, and high time it came out of its self-imposed seclusion to be measured by the standards of the West.”

His challenges were numerous. It was hard for the first-time filmmaker to raise the budget of $14,000. A black and white film with unknown actors about village life was not an easy sell. Ray had to borrow money to shoot some footage to show prospective investors; he later sold his wife’s jewelry, his life insurance policy and his record collection to raise money. Production stopped and started as he raised and ran out of funds; one hiatus was nearly a year. Some government funds were held back when the bureaucrats wanted a happy ending. Eventually, the West Bengal Roads and Buildings Department was somehow convinced that the film was a documentary on the state of the roads in Bengal just based on its title, and they gave Ray some money.

By coincidence, MoMA’s head of exhibitions and publications, Monroe Wheeler was in Calcutta in 1954 and got shown some of the footage. He was impressed and advised Ray to finish the film and then screen it at MoMA. He came up with funds as well.

The minuscule budget caused Ray to hire amateurs behind the camera as well. 21-year-old cinematographer Subatra Mitra had never handled a film camera before. A young Ravi Shanker, who subsequently became a world-renowned sitar player, was enlisted to compose the score.

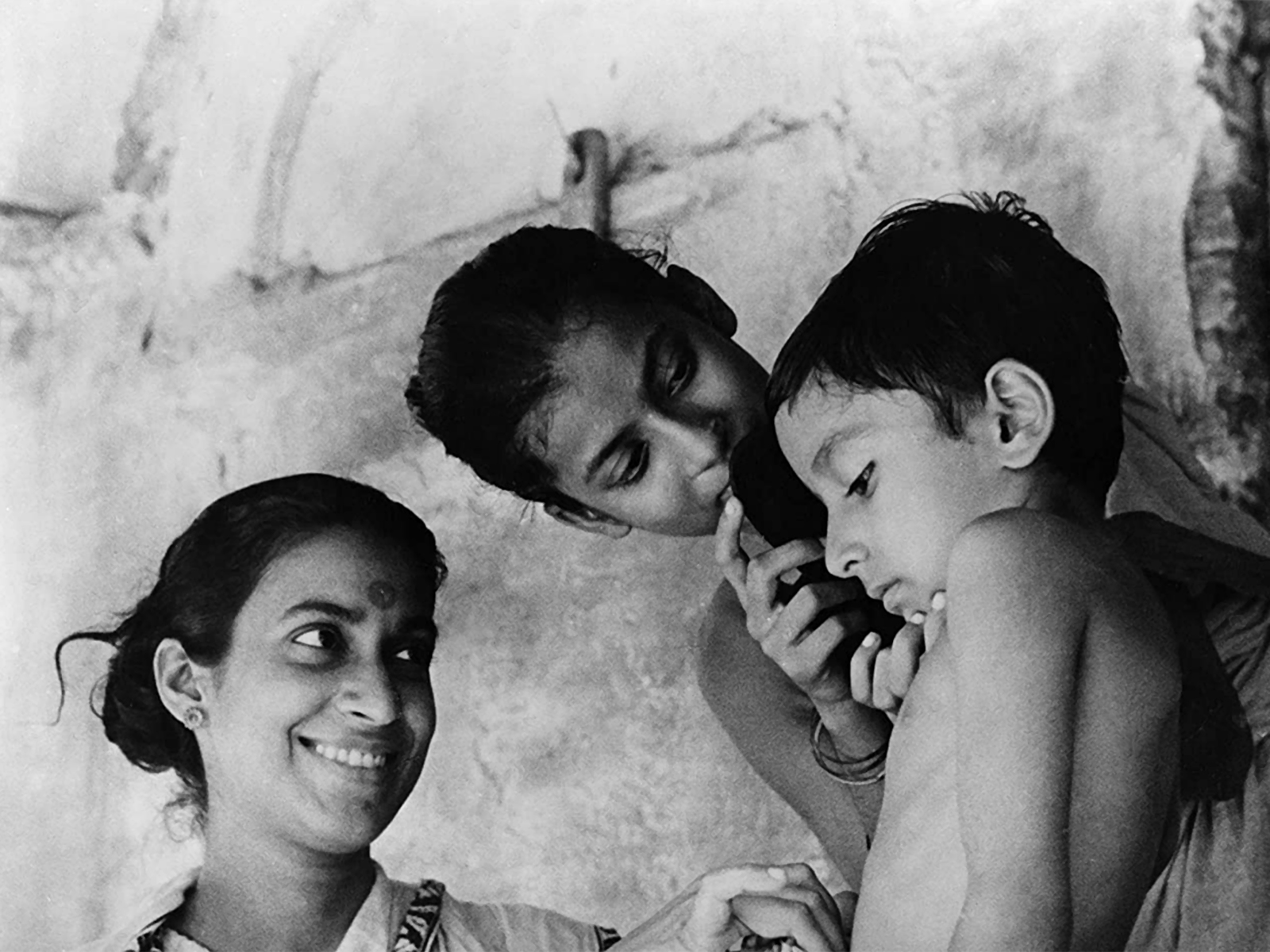

The story is set in Boral, a village outside Calcutta and tells of the lives of a family – mother, father, son and daughter, and an old aunt. The father, Harihar (Kanu Banerjee), dreams of being a poet while serving as the village priest. The mother, Sarbajaya (Karuna Banerjee), struggles to keep the family together but her desperation often gets the better of her and is manifested in the cruel treatment of the aunt (veteran stage actress Chunibala Devi who came out of retirement after 30 years). The children, Apu (Subir Banerjee) and Durga (Uma Dasgupta) somehow manage to find joy in their lives, running through the neighbor’s orchard and stealing fruit, chattering with their friends, watching shows put on by itinerant troupes, waiting for the whistle of a faraway train. Eventually, Harihar is forced to seek employment in the city as the family sinks deeper into debt. On his return after several months, he finds that matters have got much worse, and the family decides to leave the ancestral home and seek their fortune in the city. (Banerjee is a very common Bengali surname and the three actors who share the name were not related.)

The story is simple and episodic. Ray is not interested in grand gestures, just the poetry of ordinary life even in the midst of grinding poverty. Visual and sound metaphors abound and evoke mood without dialogue, such as the howling wind causing the creaking of the broken window in a rainstorm with a flickering candle showing the sweat on a sick Durga’s face, the play of the breeze on the crops as the children scamper through a field, iridescent raindrops on the river as Apu shivers under a tree. That a first-time cinematographer captured such lyrical beauty is remarkable; that a first-time director elicited performances of such truth and realism from his cast with such compassion and tenderness is even more so.

To the city-bred Ray, rural life was unfamiliar. As he describes in “My Years with Apu”, while he was welcomed into Boral and given all assistance, he needed more. “There were things I had to discover for myself. You wanted to fathom the mysteries of atmosphere. You wanted to watch the subtle difference between dawn and dusk and convey the grey humid stillness that pervaded the first monsoon showed … The more you probed, the more was revealed, and familiarization bred no discontent but love, understanding, and tolerance.”

In May 1955, Ray screened his film at MoMA without subtitles, but it was well-received. Initial screenings in India were not, but word-of-mouth built audiences. A Times of India reviewer had this to say: “There is no trace of the theatre in it. It does away with plot, with grease and paint, with songs, with the slinky charmer and the sultry beauty, with the slapdash hero breaking into song on the slightest provocation or no provocation at all.” But it had its naysayers, among them François Truffaut who is reported to have said after watching the film, “I don’t want to see a movie of peasants eating with their hands.”

When the film was released in the US at the Fifth Avenue Playhouse in New York City in 1958, it ran for eight months. American audiences were slowly coming around to appreciating films with subtitles by then. At the 1956 Cannes Film Festival, it won the Best Human Document award. In 1987, Ray was awarded the Legion d’Honneur by the President of France.

A recent fan of Pather Panchali, director Christopher Nolan who saw the film on a 2018 trip to India, said at the time, “I think it is one of the best films ever made. It is an extraordinary piece of work.”

After Ray won the Lifetime Achievement award from the Academy, a restoration project was started to preserve many of his films, including the Apu Trilogy. Original negatives of several films were destroyed by a nitrate fire in a London lab in 1993, and whatever could be salvaged was stored, then sent to the Academy Film Archive in 2013. L’Immagine Ritrovata in Bologna stepped in. The brittle film had to be rehydrated in a special solution. Restorers then spent almost a thousand hours rebuilding the perforations and cleaning the film. Duplicate negatives were sourced through Janus Films, the Academy, the Harvard Film Archive and the British Film Institute to find replacements for missing sections. The restoration was funded in part by The Film Foundation and the Hollywood Foreign Press Association.

The digital restoration was handled by the Criterion Collection over the course of six months. There is an excellent version on HBO Max.