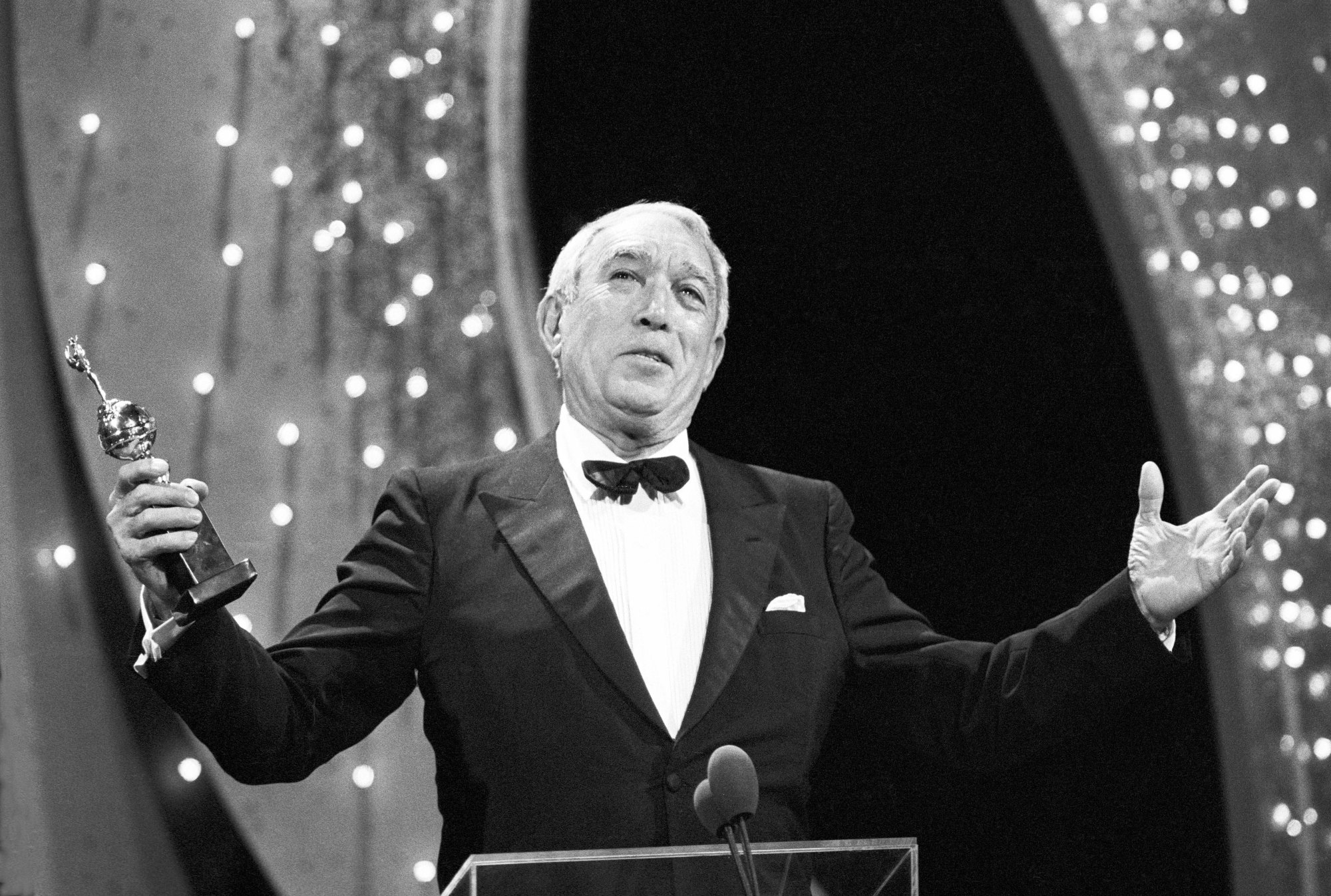

- Cecil B. DeMille

Ready for My deMille: Profiles in Excellence – Anthony Quinn, 1987

Beginning in 1952 when the Cecil B. deMille Award was presented to its namesake visionary director, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association has awarded its most prestigious prize 66 times. From Walt Disney to Bette Davis, Elizabeth Taylor to Steven Spielberg and 62 others, the deMille has gone to luminaries – actors, directors, producers – who have left an indelible mark on Hollywood. Sometimes mistaken with a career achievement award, per HFPA statute, the deMille is more precisely bestowed for “outstanding contributions to the world of entertainment”. In this series, HFPA cognoscente and former president Philip Berk profiles deMille laureates through the years.

Cecil B. deMille recipient Anthony Quinn believed his career got off to a slow start because he was married to the boss’s daughter. Some are inclined to believe that racial profiling had something to do with it.

No doubt It helped when his father-in-law Cecil B deMille used him in The Plainsman. But it was a ten-year battle for him to finally get a decent part, and even though it was a supporting role, it happened only because he had given up on Hollywood to try his luck on Broadway. That led to his being cast in support of Marlon Brando, directed by Elia Kazan, with a script by John Steinbeck, and Darry F. Zanuck producing. The movie, of course, was Viva Zapata!, for which he won an Academy Award, paving the way for a monumental career and his Cecil B. deMille award in 1987. Although nominated four times, surprisingly he never won a Golden Globe for acting.

In his two published biographies, he shows no shame: besides admitting to fathering a dozen children by various wives and sundry women, he names the numerous famous actresses he slept with. Who knew!

His professional life is another story.

After appearing in demeaning supporting roles at Paramount, where he was under contract thanks to his father in law, he switched ship and signed a contract with 20th Century Fox, where he stood out in supporting roles in notable movies such as Blood and Sand, The Ox-Bow Incident, The Black Swan, Guadalcanal Diary, Buffalo Bill, and Where Do We Go From Here?

Allowed to do outside movies, he made Back to Bataan and Tycoon at RKO, returned to Paramount for California. He got to play his first starring role in Black Gold, made for a poverty row studio, which provided him with his best opportunity and a chance to work once again with his wife Katharine deMille. They had met on her father’s The Plainsman, fell in love, and were married the same year.

By now, however, he was fed up with Hollywood and decided to try Broadway. He studied with Elia Kazan, who was instrumental in his replacing Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire on Broadway.

As a result, he was given an important starring role in The Brave Bulls, but the film was pulled from release when its director Robert Rossen was named a communist by the McCarthy committee. Again it was Kazan who turned the tide for him when he cast him in Viva Zapata!. Ironically in his memoir One Man Tango he has nothing good to say about Kazan, accusing him of being an “egotistical” manipulative director as well as a “coward” for singing to the McCarthy committee.

After Zapata, he continued to play supporting roles although his billing improved.

A decision to move to Italy, where he had been recruited by Fellini, changed his life. La Strada gained him renewed respect, especially after the film won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Motion Picture. When, two years later, he won a second Oscar for playing Gauguin in Lust for Life, his future was secured.

Now he was unequivocally a star, and after playing Quasimodo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame he starred opposite Shirley Booth in Hot Spell, Sophia Loren in The Black Orchid and Heller in Pink Tights, Lana Turner in Portrait in Black, Gregory Peck in The Guns of Navarone, Peter O’Toole in Lawrence of Arabia, and Ingrid Bergman in The Visit.

But it was Zorba the Greek which made him a screen immortal. And again, ironically, if it hadn’t been for Darryl F. Zanuck that film would never have been made.

When Simone Signoret, who had earlier won an Oscar for Room at the Top dropped out of the production, United Artists followed suit and the film was stranded without a studio. Quinn called his friend from the Zapata days and convinced him to write a check for $750,000 without seeing the script. The film became an international box office hit winning numerous awards including five Golden Globe nominations. According to Quinn, Signoret dropped out because she was “involved” with a younger man and if she played the role of 60-year-old Hortense she would lose her lover. The part then went to French stage actress and unknown Lila Kedrova, who won the Oscar for that role.

What we do for love!

After Zorba the Greek, Quinn did dozens of films but none to equal his iconic Zorba, which years later he successfully recreated on Broadway in a musical adaptation. In One Man Tango, a title derived from a nickname Marlon Brando gave him, he considers his performance in 1962’s Requiem for a Heavyweight his best work ever. Incidentally, The Secret of Santa Vittoria -for which he was nominated for the Best Actor Golden Globe- is the only film he made which won a Golden Globe for best picture.

He died in 2001 at the age of 86.

Besides being an iconic actor he was also a respected painter, many of his works are hung in museums around the world. In case you’re wondering if Quinn is his real name? His paternal grandfather was Irish, he was brought up Catholic by his Mexican mother, but in his 30s he fell under the spell of evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson; he became her disciple but never her lover. At the end of his life, he returned to that Four Square church and was buried in a Protestant cemetery.