- Cecil B. DeMille

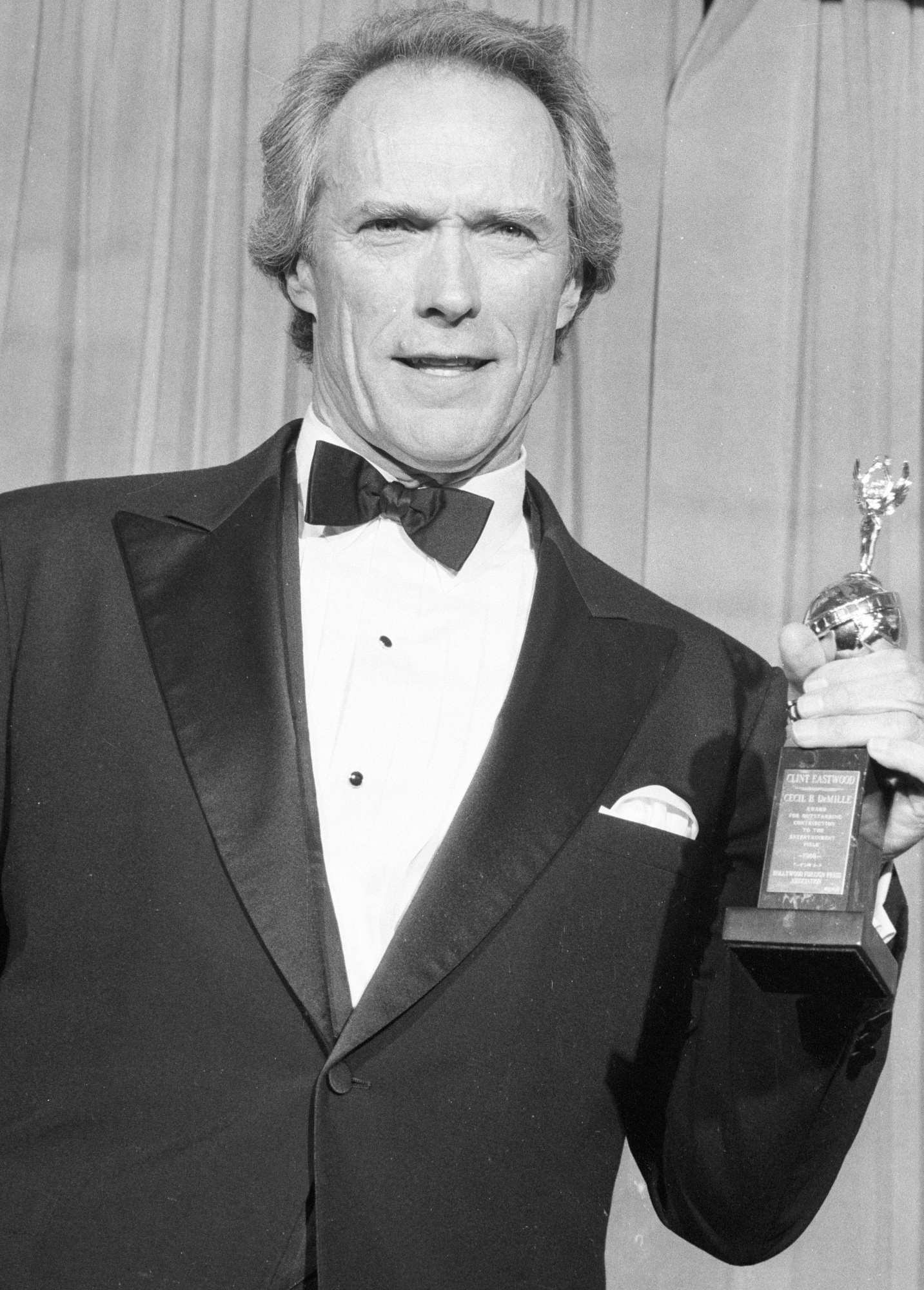

Ready for My DeMille: Profiles in Excellence – Clint Eastwood, 1988

Beginning in 1952 when the Cecil B. deMille Award was presented to its namesake visionary director, the Golden Globes has awarded its most prestigious prize 66 times. From Walt Disney to Bette Davis, Elizabeth Taylor to Steven Spielberg and 62 others, the DeMille has gone to luminaries – actors, directors, producers – who have left an indelible mark on Hollywood. Sometimes mistaken with a career achievement award, per the organization’s statute, the DeMille is more precisely bestowed for “outstanding contributions to the world of entertainment”. In this series, cognoscente and former president Philip Berk profiles DeMille laureates through the years.

Even though his film company Malpaso means misstep in Spanish, Clint Eastwood is one superstar who has rarely taken one. When asked about it he told the Golden Globes, “I’ve had few (…) I try not to dwell on them, but I’ve also made some right steps. Fate has played a great hand in my life. I have to credit that, but I’ve worked hard though not any harder than the next guy.”

Always self-effacing, Eastwood was the youngest director to win the Cecil B. DeMille lifetime achievement award. He won it primarily for his acting career, never anticipating that one day he would become one of Hollywood’s most respected directors.

But things have a way of working themselves out.

He first gained fame as a TV star, although it was his decision to work with Sergio Leone on what was then disparagingly called spaghetti westerns, which determined the outcome of his career. But that was a long time coming, and in fact, he was in his mid-30s when he made his first great movie, Leone’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.

Drafted in the army during the Korean War, upon his discharge an army buddy got him an introduction at Universal where he was given a five-year contract and appeared in boilerplate movies. Two years later he terminated that contract, following the advice of his mentor, director Arthur Lubin, whose best film was Francis, The Talking Mule! It would take another four years for him to finally find himself. He was cast as Rowdy Yates in Rawhide and the series became a big hit on CBS. He played that role for six years but he was never happy playing a 20-year-old, a character he felt was too young and boorish for a 32-year-old to play.

After the series was canceled he took a chance on A Fistful of Dollars, and from then on he never looked back. The film was a huge success and suddenly he was a major star in Italy. He followed that with three other classics, which at the time didn’t impress American critics (what did they know!) but Eastwood knew he was on to something.

He demanded and got a huge salary and 25 percent of the gross from United Artists for his first American film Hang ‘Em High which surprised everyone when it became a critical and box office hit. On the advice of his trusted business manager, he established his own production company and thus began one of the most successful enterprises in Hollywood history.

Not content to be a western actor, he teamed with his (later) favorite director Don Siegel on Coogan’s Bluff for Universal, which too was a huge success. United Artists then offered him $750,000 to costar with Richard Burton in Where Eagles Dare, which also hit the jackpot.

Suddenly he was one of Hollywood top stars who could command any role he chose.

So why on earth did he choose Paint Your Wagon, possibly the worst movie he ever made? Maybe he was seduced by the property (based on Lerner & Loewe’s Broadway musical) and a chance to work with Lee Marvin, Jean Seberg, and director Joshua Logan. That was his last misstep, although his two follow-up movies, both working with Don Siegel, Two Mules for Sister Sara, and The Beguiled were somewhat of a box-office disappointment.

Kelly’s Heroes was a return to World War 2 action films which never failed to please his public. Convinced he could do better, he tried his hand at directing. Play Misty for Me was his maiden effort, and it was a hit; from then on he alternated between acting and directing. It was his next movie, directed by Siegel, that established him as a superstar. In it, he created an identity that the public loved, and from then on he was no longer The Man with No Name but the San Francisco cop, Dirty Harry.

Instead of following it with the sequel the public clamored for, he returned to playing a cowboy ineffectively in John Sturges’ Joe Kidd but memorably in High Plains Drifter which Eastwood also directed. It was that film that pointed him in a new direction: classic Hollywood western star and director, a title he has and held onto for fifty years. High Plains Drifter was immediately embraced by highbrow critics and is considered a classic western.

Eastwood, however, chose to follow it with a Dirty Harry sequel Magnum Force which did okay business. He followed it with his own production company backing an unknown director Michael Cimino, who was later to make his name with The Deer Hunter. Their offbeat comedy, Thunderbolt And Lightfoot, helped ignite Jeff Bridges then-lagging career. His return to acting and directing in The Eiger Sanction was minor Bond, but then he made a masterpiece, The Outlaw Josie Wales.

The film did well at the box-office, but what the public wanted was more Dirty Harry, so he was again Harry Callahan in The Enforcer which to no one’s surprise did twice as well. His follow up directing job The Gauntlet offered his then steady girlfriend Sondra Locke, a great role but did just okay box office. But then an off the wall comedy, again with Locke, Every Which Way But Loose was a surprise hit and ended up his biggest moneymaker, even bigger than the Dirty Harry films.

He worked again with Siegel on Escape from Alcatraz, then paired with Locke on a number of lightweight entertainments which he also directed. One that he didn’t direct he assigned to his stunt double and pal Buddy Van Horn; Any Which Way You Can like its forerunner was a box-office smash. He hit a roadblock with Firefox, and Honkytonk Man, his worst box office performers.

But Sudden Impact (again playing Dirty Harry) restored his box office clout, and “go ahead, make my day” became a catchphrase of the decade. It also spelled the end of his relationship both personal and professional with Locke, who sued him for desertion. To regain the public trust he quickly teamed with Burt Reynolds in City Heat and Genevieve Bujold in Tightrope, but it was Pale Rider that restored his reputation as a master of the western genre.

Heartbreak Ridge which he also directed was a critical and box office hit. He reprised Dirty Harry in The Deadpool which he assigned Van Horn to direct. They also worked together on Pink Cadillac, the last movie Van Horn directed. He looked for a more personal project to direct, infusing his lifelong love of jazz into Bird for which he earned his first Best Director Golden Globe while winning the Cecil B. DeMille Award, a rare same-year combination.

Before being honored with those two awards, he had never won recognition from the HFPA or the Academy.

That would soon change.

He played a lightly disguised stand-in for director John Huston in White Hunter Black Heart, and then in 1992, he directed Unforgiven which earned him hosannas from the critics and Oscars for both producing and directing. Finally, he had the respect of the industry and everything he did from that point on was treated as an event movie.

He directed Kevin Costner in one of his best movies A Perfect World, he was impressive working as an actor in Wolfgang Petersen’s In the Line of Fire, and he directed and co-starred Meryl Streep in The Bridges of Madison County, a commercial and critical success which was nominated for a Golden Globe as best picture. He had another winner with Absolute Power, although his next three landed with a thud.

But then, he hit the jackpot twice with two of his most acclaimed movies. The first, Mystic River, won Oscars and Golden Globes for Sean Penn and Tim Robbins and he was nominated for both as best director. A year later, out of the blue, he followed it with Million Dollar Baby, which won both the Golden Globe and the Oscar for best picture and direction and was a huge box-office winner, maybe the most profitable film he ever directed.

And he was not done.

Gran Torino, Trouble with the Curve, and The Mule were all among the most anticipated movies of their year, and they didn’t disappoint. And in between, when he remained behind the camera, he earned high praise and multiple awards for Changeling, Flags of Our Fathers, Letters from Iwo Jima, which won the Best Foreign Language Motion Picture Golden Globe, American Sniper, Sully, The 15:17 to Paris, and last December’s Richard Jewell. Even his lesser films Invictus, Hereafter, and J. Edgar were treated with respect.

His one outright recent failure was Jersey Boys, despite his best intentions. Maybe he should have learned from Paint Your Wagon that musicals are not his forte. However, he has provided the musical score for most of his later films, successfully we might add.

Approaching 90, he continues to work. Like vintage wine, Clint Eastwood improves with age.

His classic movies? High Plains Drifter, Unforgiven, The Sniper.