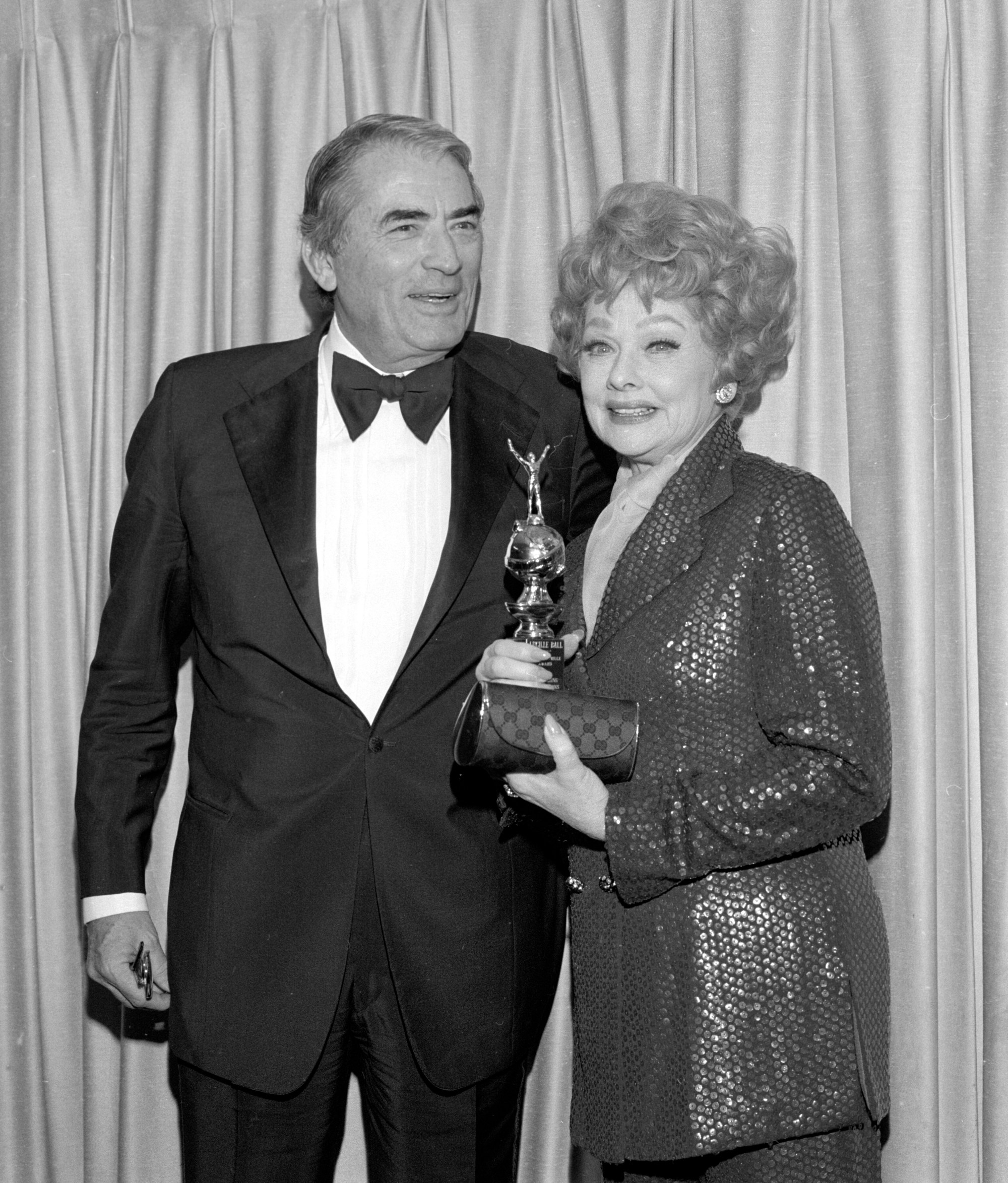

- Cecil B. DeMille

Ready for My deMille: Profiles in Excellence- Lucille Ball, 1979

Beginning in 1952 when the Cecil B. deMille Award was presented to its namesake visionary director, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association has awarded its most prestigious prize 66 times. From Walt Disney to Bette Davis, Elizabeth Taylor to Steven Spielberg and 62 others, the deMille has gone to luminaries – actors, directors, producers – who have left an indelible mark on Hollywood. Sometimes mistaken with a career achievement award, per HFPA statute, the deMille is more precisely bestowed for “outstanding contributions to the world of entertainment”. In this series, HFPA cognoscente and former president Philip Berk profiles deMille laureates through the years.

No actress, let alone a Cecil B. deMille award winner, ever struggled for recognition as did Lucille Ball. How she withstood those years of rejection is testament to her fortitude and determination.

Much of that struggle happened at RKO studios, which had no idea how to use either her beauty or her talent. It’s a crowning irony that 40 years later she owned that studio. When you think of Lucille Ball’s movie career you think of that beautiful redhead who was equally at home playing dramatic roles and crazy comedies.

Of course, it was TV that made her an icon, arguably the most beloved of all TV personalities. But she languished for years at three major studios. First, there was RKO that signed her to a standard seven-year contract. The best thing (or maybe worst) that happened there was her meeting Desi Arnaz on one of her many forgettable films. He swept her off her feet, she fell in love, they were married, but he was always unfaithful.

Someone as smart and beautiful should have known better, but love has its reasons. At RKO after five years of menial parts, she graduated to supporting roles in Edna Ferber’s Stage Door and the Marx Bros. Room Service, finally achieving starring roles in films best forgotten.

It was Dance Girl, Dance, however, directed by the only woman director at that time, Dorothy Arzner, that must have kindled MGM’s interest, and when her seven years were up, they signed her to a long term contract.

No doubt Arthur Freed had something to do with that, but again, at MGM, she was misused. Her first role, a screen adaptation of Broadway’s Du Barry Was a Lady, made her look ultra-glamorous in Technicolor, but it was more a showcase for MGM’s top comedian Red Skelton. Freed commissioned new songs for the movie, a slight to composer Cole Porter, but in fairness, there really is only one great song in the entire show, one which was reprised 40 years later when Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby sang it in High Society. The title: “Well, Did Ya Eva? (What a Swell Party It’s Been.”)

She followed that with the solo lead in Best Foot Forward and then did guest spots in Thousands Cheer and Ziegfeld Follies, both prestige showcases. Going nowhere fast, she shared the screen with Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn in one of their weakest efforts Without Love. She was borrowed by Fox for a film noir, The Dark Corner, and then by Universal for a screwball comedy Lover Come Back, returned to MGM for her last movie there, Easy to Wed in which she played second fiddle to the studio’s top stars Esther Williams and Van Johnson.

So much for her MGM venture.

Her last films before I Love Lucy were at Columbia where she was The Fuller Brush Girl and Paramount where she found her comedy soulmate, Bob Hope. Their two movies together, Sorrowful Jones and Fancy Pants were her two best ever and huge box office hits. But still, it was Hope who was the star.

Her final film, The Magic Carpet, convinced her to try television and the rest is history.

I Love Lucy ran for six years. It was the most-watched show in the US for four of its six seasons, and it’s still being seen in dozens of languages the world over. Ball was nominated for 13 Primetime Emmy Awards, winning four times. In 1960, she received two stars, for her work in both film and television, on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

During her spectacular success with Lucy, MGM invited her (and Desi) back to the studio where they made two quality movies, The Long Long Trailer and Forever Darling. Both box office and critical successes. For the first, she had Vincente Minnelli as her director and for the second, James Mason in support. Now she was Hollywood royalty.

But she preferred to work in television and waited four years to return to movies and then only if they were good ones. So she made The Facts of Life and Critics Choice with Bob Hope, and Yours, Mine, and Ours with Henry Fonda, but TV was now her medium of choice.

Meanwhile, her years of struggle had enabled her to become a shrewd businesswoman. Her smartest move was making her deal with CBS for only one-time broadcast rights. When CBS bought back the rebroadcast rights they paid her and Desi enough money for them to acquire RKO studios, which they renamed Desilu Pictures.

As a creative studio head, she pioneered TV packaging that made possible the Mission Impossible and Star Trek series. In 1974 at the height of her TV fame she was lured back by Warner Bros. to star in a blockbuster musical version of Broadway’s Mame, recreating the role made famous by Rosalind Russell in the 1947 film, and Angela Lansbury in the Jerry Herman stage musical.

That misstep was her undoing. Neither the critics nor the public took to her in that role, and she never did anything memorable after that.

Lucille Ball was nominated for six Golden Globes but never won, seemingly a prerequisite to winning a Cecil B. deMille award.

She died in 1989.