- Cecil B. DeMille

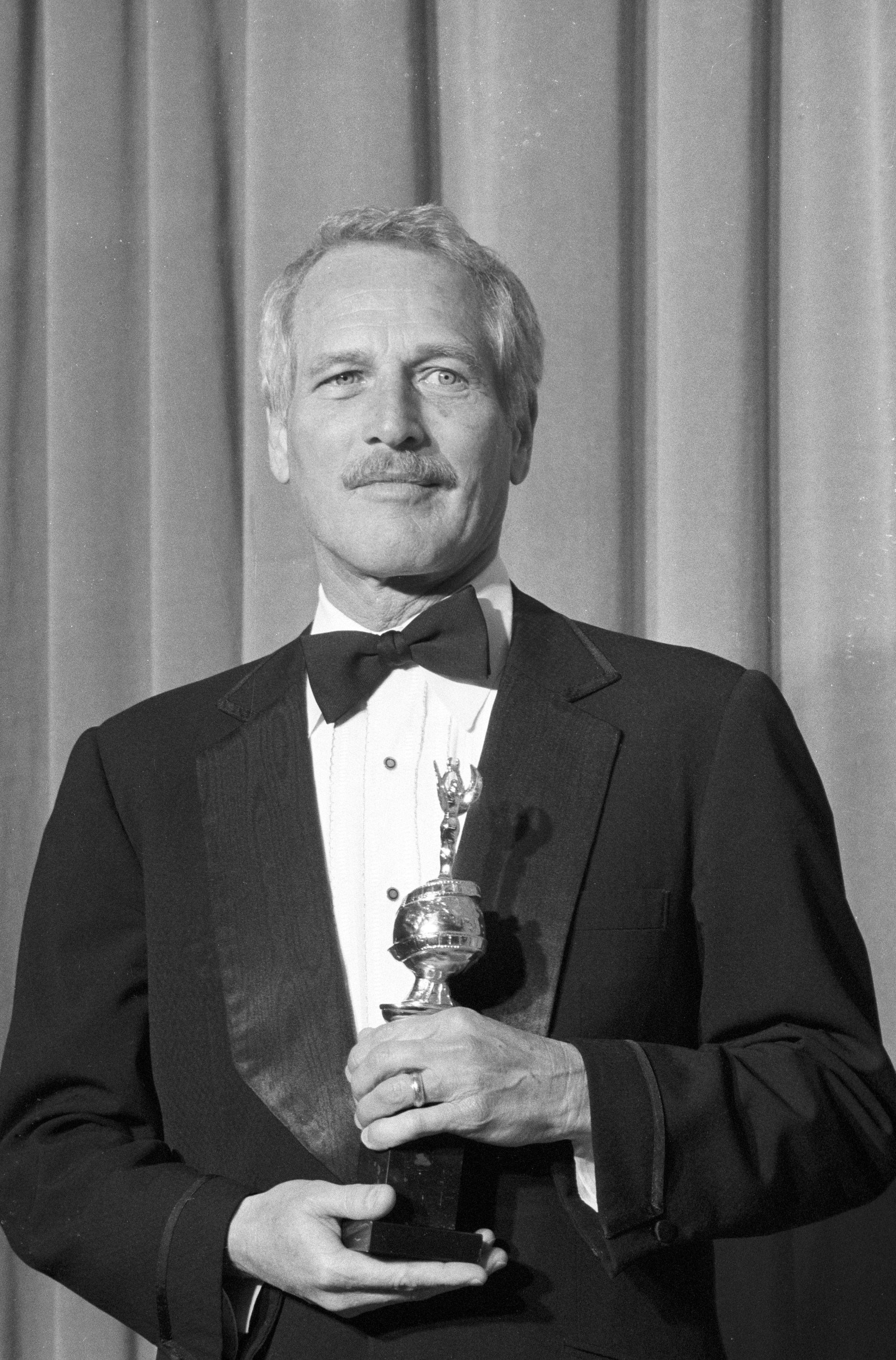

Ready for My deMille: Profiles in Excellence – Paul Newman, 1984

Beginning in 1952 when the Cecil B. deMille Award was presented to its namesake visionary director, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association has awarded its most prestigious prize 66 times. From Walt Disney to Bette Davis, Elizabeth Taylor to Steven Spielberg and 62 others, the deMille has gone to luminaries – actors, directors, producers – who have left an indelible mark on Hollywood. Sometimes mistaken with a career achievement award, per HFPA statute, the deMille is more precisely bestowed for “outstanding contributions to the world of entertainment”. In this series, HFPA cognoscente and former president Philip Berk profiles deMille laureates through the years.

Cecil B. deMille honoree Paul Newman to the end was erudite, urbane, and whimsical (his favorite word) although not to the manor born. In fact, he came from a middle-class family that owned a sporting goods store in Shaker Heights, Ohio.

Interested in acting even as a child, his ambition was interrupted by WW2 during which he served with distinction. After the war, he completed his bachelor’s degree and attended Yale School of Drama for a year before moving to New York to study under Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio. He made his Broadway debut in Joshua Logan’s production of William Inge’s Picnic, which won all the awards that year, never mind that its competition was Arthur Miller’s (anti-McCarthy), classic The Crucible. For the run of the play he understudied the lead and played a supporting role, and when the play went on the road and he asked to play the lead, he was told by Logan, as he later told the HFPA, “I couldn’t take the part on the road because I had no sex appeal.”

Although he later acted on Broadway originating the leading roles in Desperate Hours and Sweet Bird of Youth it was Hollywood that occupied him for the next 60 years, and what a career he had.

When he arrived in Hollywood he faced stiff competition. This was the era of Montgomery Clift, Marlon Brando, and James Dean.

Warner Bros. signed him to play opposite Virginia Mayo in The Silver Chalice, a move he so regretted he took out a full-page ad in The Hollywood Reporter to apologize for his acting.

Talk about chutzpah.

But then fate intervened when James Dean was killed in a motor car accident just as he was about to start a film about prizefighter Rocky Graziano. Newman was chosen to replace him in Somebody Up There Likes Me, which made him an overnight star. Obligated to a four-picture deal at MGM, he was cast in The Rack, Until They Sail, and on loan out to Warner Bros. for The Helen Morgan Story, none of which did much to further his career. What established him as a superstar was The Long Hot Summer, where audiences suddenly discovered his brilliant blue eyes (the film was in color) although his costar Joanne Woodward might have had something to do with it. The two of them had met seven years earlier when they both understudied the leads in Picnic and fell in love. Because Paul was married and the father of three they kept the relationship private. A year earlier Joanne had won the Golden Globe and the Oscar for Three Faces of Eve. Long Hot Summer rekindled their romance, and after Paul’s wife agreed to a divorce they were married and remained married for 50 years. From then on he was able to call all the shots.

His first attempt to do something meaningful was The Left-Handed Gun, a revisionist version of Billy the Kid. Despite a script by Gore Vidal and Arthur Penn directing, it was a commercial failure and not well received by critics. Paul had learned his lesson. Stick with the advice of professionals. His follow up movie with Elizabeth Taylor was both a commercial and critical success. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof landed him his first Oscar nomination, and the film itself was nominated for both a Golden Globe and an Oscar as best picture. It was not just those brilliant blue eyes that were attracting audiences around the world. Now he was second only to Brando in the acting department.

As a free agent, he followed that with several commercial hits- The Young Philadelphian and From the Terrace – and with Otto Preminger‘s Exodus he had his first blockbuster. But then he faced his first great acting challenge playing Eddie Felson in Robert Rossen’s masterpiece The Hustler. He was nominated for both a Golden Globe and an Oscar for that performance, and he should have won for both.

After a stint on Broadway originating the role of Chance Wayne in Tennessee Willians Sweet Bird of Youth, he played that role in Richard Brooks film version, another box office hit for which he was again nominated for a Golden Globe.

And again, the following year, he was nominated for Hud, his first unsympathetic role. Both his costars (Patricia Neal and Melvyn Douglas) won Oscars, but he had to content himself with a nomination.

In between these films he found time to work with his wife on Rally Round the Flag Boys, Paris Blues, and A New Kind of Love, all middling successes. And he had no better luck with his next batch of movies. The Prize, based on a big bestseller, What a Way To Go, an all-star fiasco, The Outrage, a tame remake of Kurosawa’s Rashomon, and Lady L with Sophia Loren.

Were his best days were behind him? The role of a washed-up private eye in Harper suddenly reignited his career. Hitchcock recruited him for Torn Curtain (not a happy association) and Cool Hand Luke earned him his third Golden Globe and Oscar nomination, quickly becoming his most iconic role, attracting new fans like no other.

And yet the best was still to come. Teamed with Robert Redford, as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid both became the stuff of legends. The movie was his greatest commercial success and easily his best-loved film. Now at the top of his game, he wanted to make films that mattered. So he produced and starred in WUSA, an expose of right-wing politics, which failed to connect with either critics or audiences. He followed that with two films with director John Huston, The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean and The MacKintosh Man, both outright failures.

Once again it was Robert Redford to the rescue. They teamed up again for the upset Oscar-winning best picture The Sting, which the public flocked to, making it the biggest moneymaker of the year. After that, there was another blockbuster: The Towering Inferno, this time his costar was Steve McQueen, but essentially his career was now over.

He worked unsuccessfully with Robert Altman on Buffalo Bill and the Indians and Quintet, made a comeback with Sidney Lumet on The Verdict, again Oscar and Golden Globe-nominated. He finally won a long-overdue Oscar for The Color of Money directed by Martin Scorsese reprising the role of Eddie Felson, his The Hustler role which had denied him the Oscar 20 years before.

After that he worked intermittently, rarely successfully; in fact, his most memorable role of his latter period was voicing Doc Hudson in the animated Pixar movie Cars. We interviewed him shortly before he died. He was still erudite and patrician, but noticeably frail.

To the end, he was a Hollywood immortal. He might have had a checkered career but there was no shortage of great performances. The Hustler and Cool Hand Luke ranking close to the top.