- Festivals

Rotterdam 2022: Tea Lindeburg’s “Earthly Heaven”

Tea Lindeburg’s feature film debut, As in Heaven, premiered at the Rotterdam and Göteborg film festivals simultaneously and received the top Dragon Award for Best Nordic Film at the latter.

Lise (Flora Ofelia Hofmann Lindahl) is the eldest child of a large rural Danish family at the end of the 19th century. While she is already determined to get a higher education in the city – not a path followed by many at the time, and certainly not by women – her mother is expecting another child.

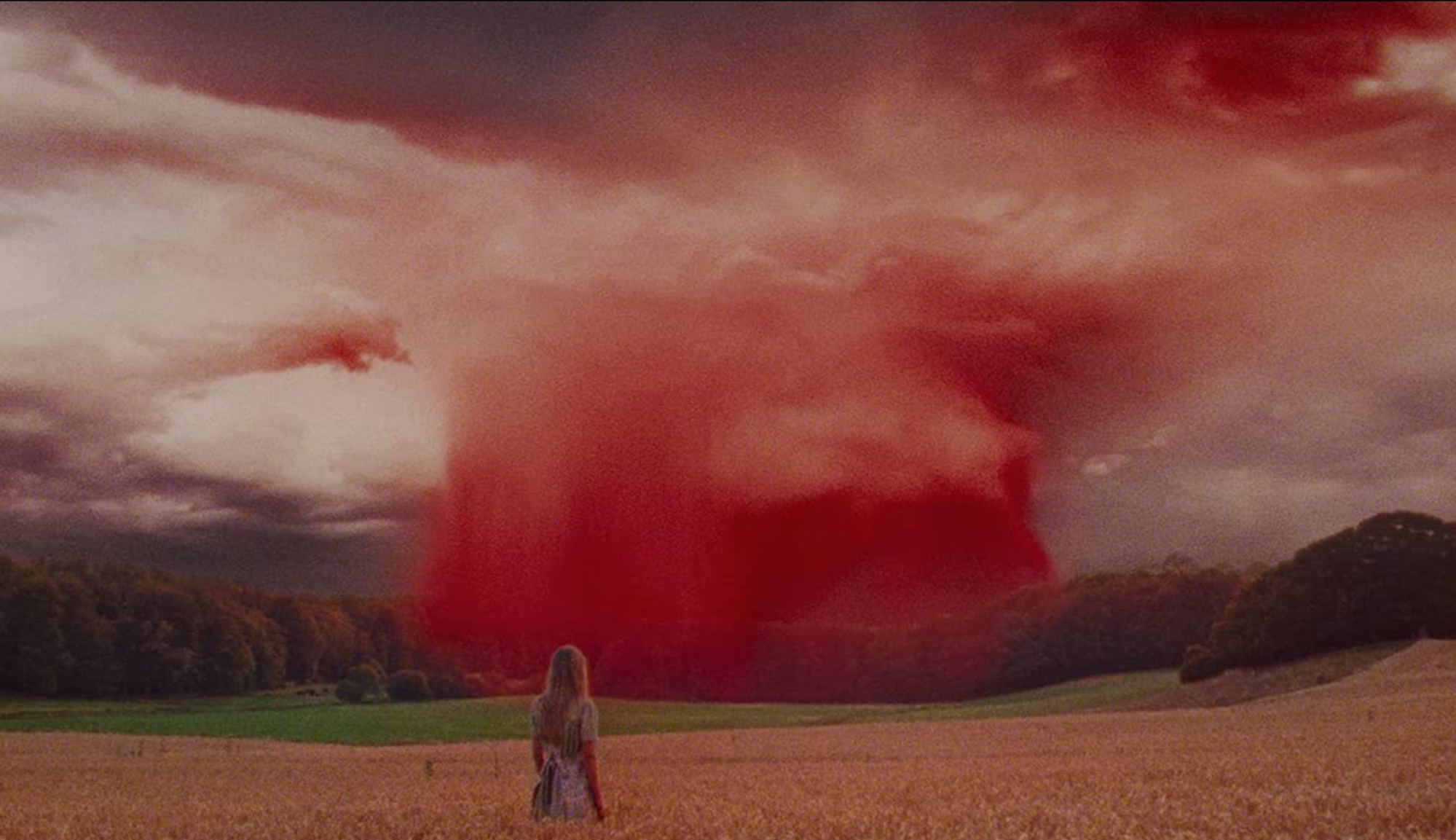

The idyllic environment of meadows, streams and flowers – the playground of these angelic and healthy-looking brothers and sisters and cousins, of different ages but each just as carefree as the other – suddenly turns into the stage of Lise’s growing-up. Childbirth complications thwart everyone’s expectations, especially those of Lise, who goes on a quest to save her mother.

The film is based on Marie Bregendahl’s A Night of Dying, which was written in 1912. Lindeburg read the novel three weeks after her son was born and was immediately drawn to it. “The book is told from an all-knowing perspective,” she says, “kind of like a god looking down at the little human beings in the world”.

Visualizing it as a movie, however, she immediately knew that the story must be told from the perspective of the children, particularly Lise.

The director has successfully transmitted a layered, mostly internal story from the page to the screen. It’s as if she has brought to life its spirit without violating the feminine sensibility that created it in the first place. At the same time, the film is never anything but captivating.

Central to the story is the characters’ relationship to spirituality. At the time the story took place, everyone in Denmark “was extremely Christian – there was no question about that – but everyone also believed in dreams and visions,” Lindeburg explains.

When her mother is in danger of dying, Lise goes out on her own and prays. She asks God to forgive her for being a bad daughter, for losing her mother’s silver pin, for being disobedient … and begs Him to keep her mother safe. “Do you forgive me?” she asks, and a gust of wind blows on her face. “The wind is God saying, ‘I am here’, but then you also realize in the end that you cannot bargain with God.”

Yet the issue of bargaining with faith, now gaining it, now losing it, underlies the whole story, Lindeburg continues. As in Heaven never loses a sense of ambivalence from the beginning to the end. Neither the heroine nor the audience is in a position to know who is right or wrong – whether science, superstition, or religion can claim any part of the truth.

“There is no clear answer,” says the director. “Lise just has to find meaning in the life that she is given.”

Can a place where life happens be “as in heaven”? Does suffering preclude worldliness from finding spiritual meaning in the here-and-now? “[Heaven] doesn’t start after we die,” Lindeburg responds. “We don’t reach something divine on the other side. I think that this life that we have, and we are given – we’ll have to make it as heavenly as we can, even though there is so much sorrow and so much pain.”

Perhaps it is this point that may be key to understanding the director’s vision: that the world is beautiful, even in the face of suffering. “I wanted to make [a film] that is honest, but I did not want to depict a life that was just brutal.”

The children’s lightness counterbalances the sadness. “We wanted colors and we wanted it to be beautiful,” Lindeburg points out. Then, she tempers her enthusiasm: “Of course, this opens the discussion – what is beautiful?”

For her at least, beauty is in conveying a “poetic and a sensitive feeling.” The fact that it is shot on 16 mm film, along with the absence of a music score, adds to the atmosphere of the film. More than any design elements, however, beauty in As in Heaven consists in transmitting the magic of childhood.

We are reminded of the lost magical time of childhood when the grassy paths are there for bare feet to tread on, dandelion flowers to be blown in the wind, haystacks to be jumped around, plank bridges to be run across, butterflies to marvel at … when the whole world is a constant play of discovery and joy.

“It’s very much the feeling of my own childhood,” Lindeburg admits. “I remember as a child having those days when we would be a bunch of children on our own, without adults texting us all the time. There were no phones, [our parents] didn’t know where we were, we just had to be home by eight! … That freedom is gone.”

Unquestionably, As in Heaven is told from a feminine perspective. As such, it belongs to a new crop of films that reveal the inner workings of the female psyche.

When the father comes back after a long day of work and finds his home in disarray, he punishes Lise with a slap in the face. She is shocked but does not respond. Her red cheek is the only sign of her pain – the pain she has endured inside.

At that moment, female audience members can only sympathize with a situation some of them know all too well. No matter how Lise tries to make things better, in the end, she is made to feel guilt and hurt in addition to her own internal turmoil.

But the director does not blame the male character. “He feels inadequate,” she says. “He doesn’t know what to do. He doesn’t know how to express his emotions. The only way he can react in that situation is taking it out on Lise.”

“I don’t think that men are evil, at all,” she adds a little later. “But it was also a time when they were not brought up to express their feelings … [The father’s] character is extremely interesting, I would love to tell his story as well, [but] this is just not his story … It’s Lise’s story”.

The interior life may be claimed as a strong point of attraction among female creators. The realm of emotions has always been familiar to the women of the world, yet it would be utterly presumptuous to suppose that women are exclusively endowed to tell stories about feelings.

Lindeburg relates to the work of Carlos Reygadas whose Silent Light shares some features with As in Heaven. “It’s such a slow film,” she says of Silent Light

Likewise, As in Heaven follows a slow rhythm – one that is dictated by the internal movements of its characters. The fact that this director can hold her audience’s attention from beginning to end is a testament not only to her ability but also to her boldness. “This film has been hard to finance,” she confesses. “In the beginning, everyone would say ‘there is no story, there is no plot.’” But Tea Lindeburg knew better.