- Festivals

TIFF 2022: Werner Herzog’s “Theater of Thought” Examines Intersection of Science and Human Brain

Throughout a long and distinguished career, the most defining characteristic of Werner Herzog’s canon has been sheer variety, driven by an enormous sense of curiosity. In his prolific documentary work, the 80-year-old German filmmaker has shown an intense interest in people (Little Dieter Needs to Fly, Meeting Gorbachev), in addition to the natural world and its history, both culturally and scientifically (Cave of Forgotten Dreams, Fireball: Visitors From Darker Worlds).

Oftentimes, these interests line up, especially in explorations of figures who place themselves in rather extreme living conditions (most famously Grizzly Man, but also Encounters at the End of the World as well as the upcoming Fire of Love, about volcanologists Katia and Maurice Krafft).

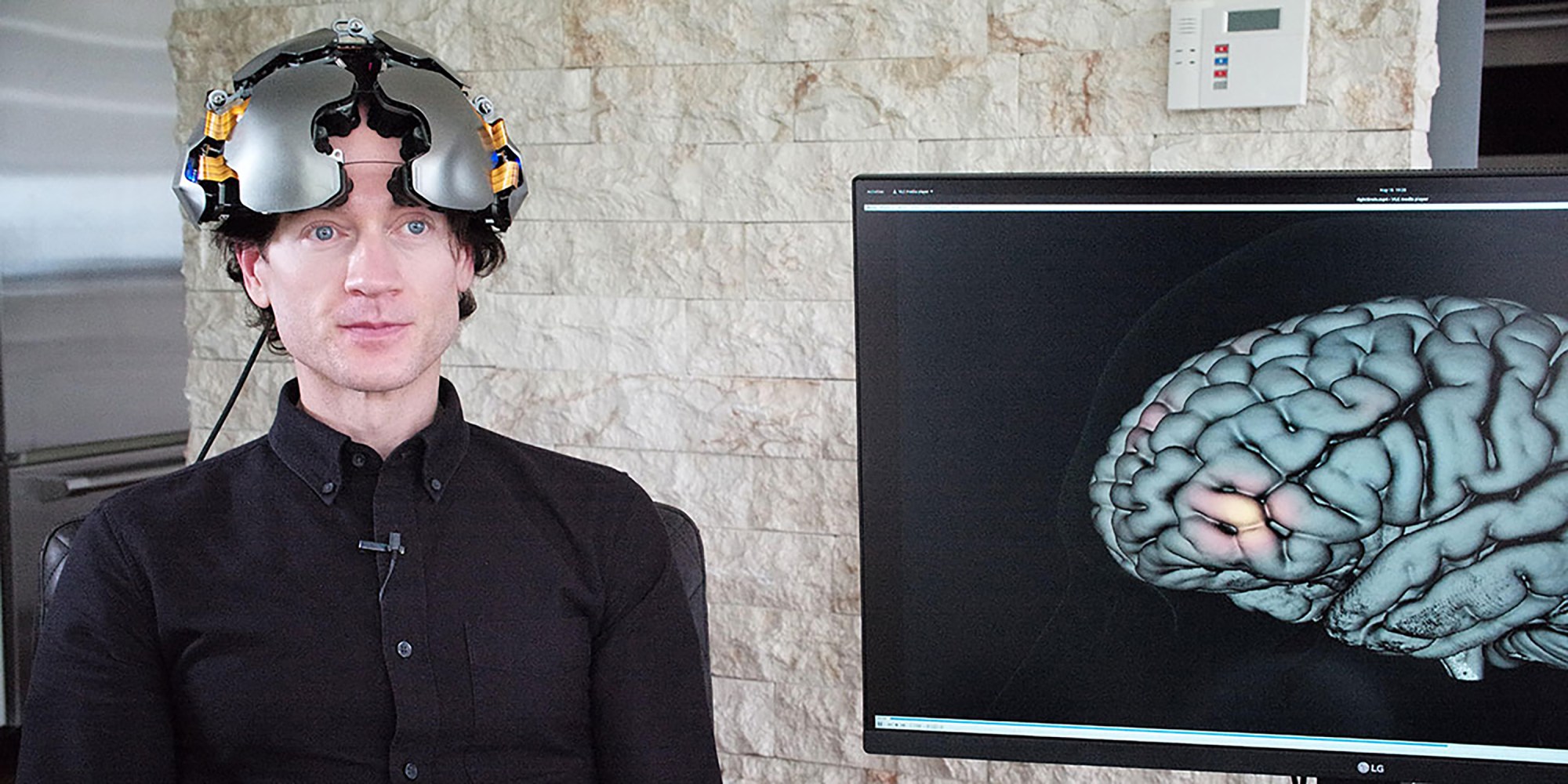

In his fascinating new nonfiction offering Theater of Thought, however, which just enjoyed its international bow at the Toronto International Film Festival only days after premiering at Telluride, Herzog turns much of his inquisitiveness inward, speculating in whimsical fashion on whether humans of the future will have autonomy over our own ideas and judgments, or whether our brains will inevitably become fused with technology in the coming decades.

Gathering insights and predictions from some of the most influential innovators and scientists working in various fields, Theater of Thought unfolds as a loose-limbed field trip with incredible access — the coolest theoretical scholastic presentation you never had a chance to experience as a teenager. It’s a heady and good-humored exploration of both the ethical and existential questions that neural technology raise in our modern world, where rapid advancements in research and processing routinely outstrip robust and thoughtful public policy discussion, and certainly any regulation.

And, in a wide-ranging introduction at his movie’s festival presentation, the director noted both his long-standing fascination with issues of self-deception and delusion, and personal connection to the mysteries of the brain. “My own father pretended and lived under the pretext of writing a universal study, and for that he had to read books — he was always reading and taking notes,” said Herzog. “And he claimed from a certain time that he had actually written the book, though he’d never written a single line. But he was completely convinced, he’d talked himself into it. So it was almost like a ghostwriter that told him that he had written this study. And so, I was puzzled now — was it really me who made all these films, or am I just talking myself into it?”

Later Herzog joked, in reference to a passage in his movie, about predictive artificial intelligence being able to sequentialize footage or even entirely manifest his films into existence based merely on his thoughts about different subjects.

The list of interviewees in Theater of Thought is incredibly long, from noted neuroscientist Christof Koch and IBM Senior Vice President and Director of Research Dario Gil to Siri co-creator Tom Gruber and married scientists Cori Bargmann and Richard Axel, the latter of whom Herzog takes great delight in peppering with off-kilter questions. Philippe Petit, the high-wire performance artist who famously traversed the space between the top of the World Trade Centers in 1974, even pops up.

One of the film’s most interesting passages centers on the research of Dr. Rafael Yuste, a neurobiologist and Columbia University professor who studies hydras, the first known animal with a nervous system. The unique ability of these tiny creatures to have their neurons completely scattered and then entirely reconstitute themselves (think the T-1000 from Terminator 2: Judgment Day) has considerable implications. Equally engrossing are segments on brain-computer interfaces, which have wonderful practical uses (unlocking thought-directed motion in quadriplegics, and sight in the blind) but also have potentially darker applications, as evidenced in studies which have achieved the involuntary control of movement in mice.

If this sounds boring or overwhelming, it’s the furthest thing from it. Through it all, while still indulging his characteristically droll narration (sample: “The New Jersey turnpike allows no hint of the past”), Herzog keeps the proceedings lively, and smartly paced. He uses pauses (and his own befuddlement or disinterest with incredibly specific scientific elucidations) to great comedic effect.

Herzog also ducks into narrative alleyways that yield great revelations, as with an exploration of the concept of collective blindness in schools of fish which translates all-too-readily to human society. Probing and intelligent, Theater of Thought is like catnip for those with a curiosity about our world, and what the future holds.