- Festivals

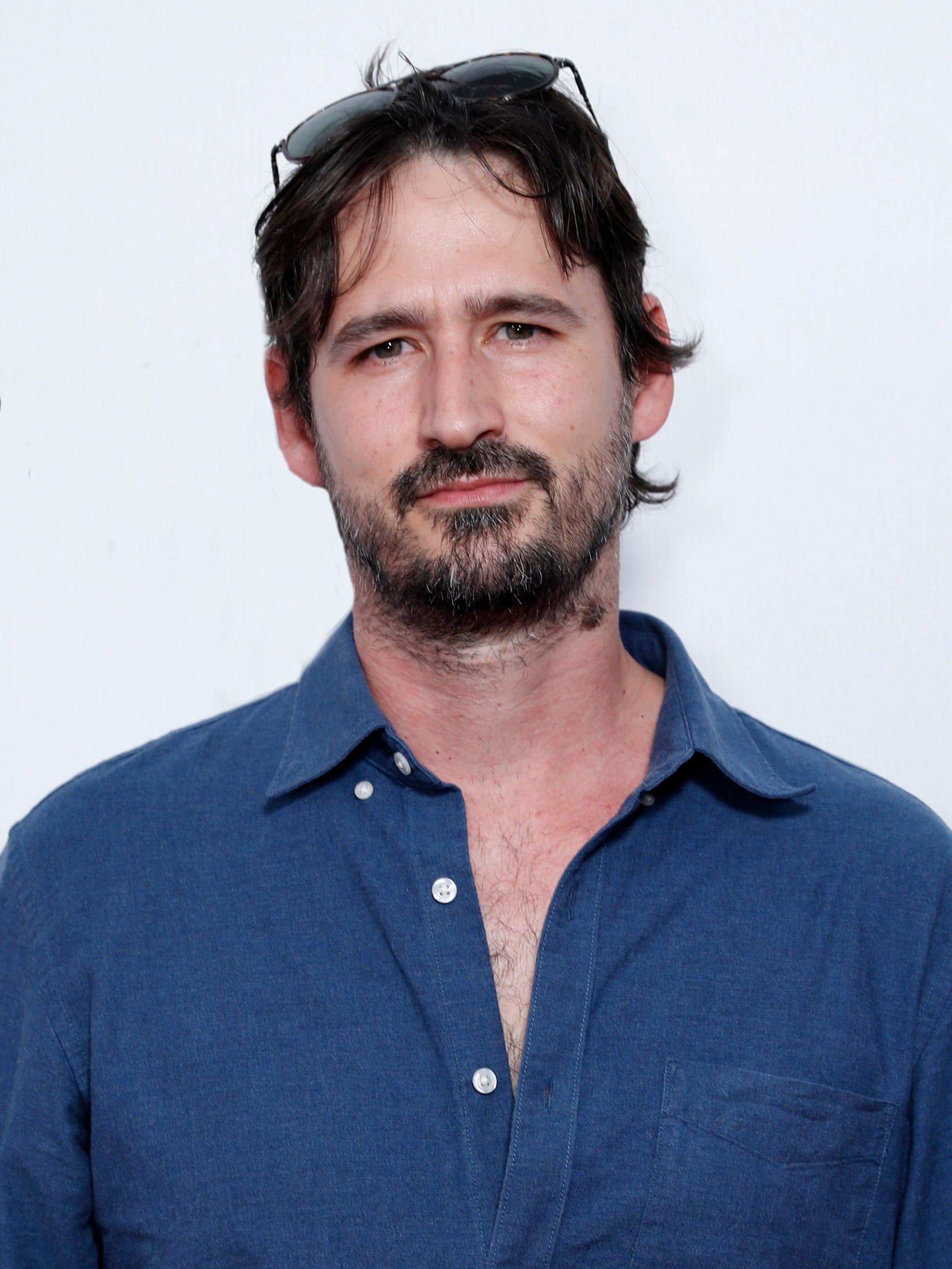

Ulises Porra: Exclusive Interview – “Carajita” and the Last Bit of Humanity

Guadalajara International Film Festival Winner

Night time. The silhouette of a woman prostrated on the sand at the ocean’s surf. Police lights flash on her from behind. She ignores them. The image is pinned in your head. You know you’ll find out later.

Sarah (Cecile van Welie), the willowy daughter of a wealthy family in the Dominican Republic, loves Yarisa (Magnolia Nunez), the Afro-Caribbean nanny as if she were her mother. Yarisa loves her back. Like a daughter… always, unconditionally.

Knowing that her dad is corrupt, her mom indifferent and her brother idiotic does not disrupt a daily life luxury and pleasure. Yet, it would, but Sarah can always count on Yarisa’s anchor to keep her grounded and on the special gift of being able to hold her breath underwater for an extended time. She often submerges herself in order to go to her “favorite place” of quiet and bliss.

The unexpected visit of Mallory (Adelanny Padilla), Yarisa’s charming biological daughter, does not faze Sarah. In a brief exchange between them, Mallory asks Sarah if her mother loves her. Sarah replies affirmatively. A potential instant of jealousy vanishes in the camaraderie of sisterhood.

Things change rapidly when, suddenly, Mallory disappears – she is soon found dead, the victim of a hit-and-run accident. Yarisa and her working-class family are devastated. In a brilliant moment of dramatic irony, the creators put the audience inside Sarah’s mind: the night before, when driving home in the pouring rain from a party, she thought she had hit a sheep. Now she realizes it was Mallory. But she cannot share her secret with anyone – most of all, not with Yarisa. When Yarisa begs to see Sarah, Sarah refuses to go near her. Instead, she spends long intervals underwater.

Craftily, the filmmakers lead the drama toward its resolution without ever losing sight of the bond between the two women. In the swirl of shifting forces, what had been an irresistible and opposite-pole attraction has become a deep sense of repulsion forged by guilt, shame, and shattering pain.

The film keeps tension tethered tightly between love and fear until the end. Until everyone in the family knows. Until everyone in Yarisa’s family knows. Until Yarisa knows. But justice is not written in the laws of nature. The wealthy continue to enjoy immunity while the poor must endure the consequences of injustice. Mallory’s tragic death will come to pass as if it had never happened.

Magnetic fields have no regard for human activity. Yarisa’s whole being is trained toward and consumed by a single urge: to summon the daughter that is left to her, Sarah, the nymph sitting at the bottom of the ocean.

Dominican writer-producer Ulla Prida invited writer-director Silvina Schnicer from Argentina and Ulises Porra from Spain to bring her story of the “brat” (Carajita) to life. The idea grew on the soil of colonialist dynamics generated by eons of clashes between the privileged, the underprivileged, and the real emotions that spring in their midst.

Although the central incident of the story is an accident, the film is about politics in a very real sense, Porra told the HFPA in an interview at the Guadalajara International Film Festival where it received the top prize in the Ibero-American Features section. “Love can happen between people who come from different strata of society but when reality hits, will these relationships prevail?”

Porra doesn’t think so. “The structure of our lives depends on our [social] position. We didn’t want to judge Sarah, Yarisa, or Sarah’s family; we just wanted to look critically at the system to which they belong.” In the Dominican Republic, the ruling, mostly white class comprises 2% or so of the entire population. “Every character does what they’re programmed to do,” he continued. “At the same time, individually, each character is trying to do their best with the tools that they have”.

For the Schnicer/Porra duo, character self-reflection – or “soul-travel” as Porra calls it – has always been important. It is as if they hold a scale weighing social expectations on one end and humanity on the other. For example, Sarah and Mallory are pitted against each other by life “but, when you put them together, they reach for one another and what they say is profound … If the accident hadn’t happened, the relationship between these two girls could have been a rich one.”

“This is the power of the movie,” he went on. “We show what could be if we talked to each other, beyond the place where we are planted.” Yet, Porra (along with his partner Schnicer) insists that this beautiful possibility is doomed. “In this world, when reality grabs you it is so hard to go on with love.”

“This movie was begging us not to have a naïve message,” he explained. “In 99% of situations like this, the powerful are free and the powerless don’t find justice. But, hopefully, after all… maybe. In the case of Sarah, for example, she may realize that the path she chose comes to an end.” In honor of the 1% of humanity left in the world, the filmmakers subtly suggest that Sarah’s “soul-travel” is not over and that she is still thinking of Mallory and Yarisa.

“There is something of them in her,” he said. “That is what we need: to have something of the others inside of us”. Sara’s biggest problem is not about the police, justice, or family. “It is that she cannot be seen by Yarisa’s eyes after what she has done. The reason she doesn’t confess is not that she is afraid of going to jail or something, but that she cannot confront Yarisa.”

Ultimately, what Sarah longs for – perhaps, what we all long for – remains unchanged from the beginning to the end of the story: to return to the place where she and Yarisa can become one, just as mother and baby are in utero.