- Interviews

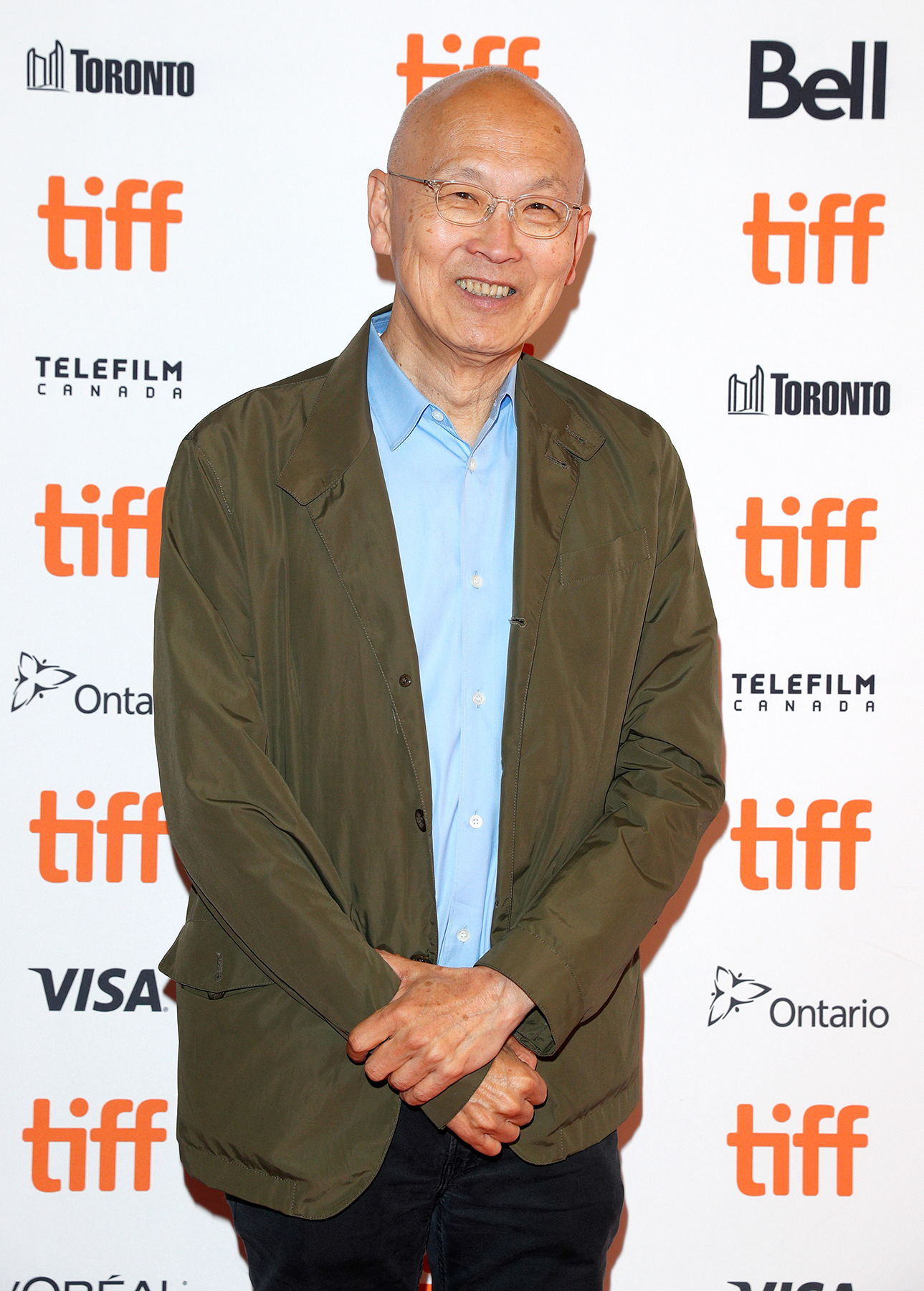

Wayne Wang: ‘In my career I’ve been avoiding being put inside a box’

normal’>The Joy Luck Club, the film that showed Hollywood studios that audiences were not afraid of an Asian cast if the story was good. But he was just as good adapting Paul Auster’s complex New York stories to the screen in the memorable Smoke (and its companion, piece Blue in the Face, co-directed with Auster). Wang has directed films in China and Japan, and also Hollywood films such as Maid in Manhattan and Because of Winn-Dixie. If his goal as a filmmaker has been to avoid typecasting, as he says in this interview, certainly the 71-year-old Hong-Kong native who moved to the US at 17 to study photography, can say that he has achieved it. Always experimenting, Wang started to plan Coming Home Again, his latest venture, as a virtual reality film. Shot entirely in an apartment in San Francisco where he currently lives, the movie tells the story of a man (Justin Chon) trying to cook a perfect Korean meal for his dying mother (Jackie Chung), exactly as she always prepared it for him while he was growing up.

normal’>Coming Home Again, also referring to your filmmaking? It seems like it’s a return to your origins in a way.

Smoke too. I have a small crew, I know everyone, I like to talk to everyone, it’s really a dream come true. And like I said, I can do anything: I can say to the producer, “I don’t feel like in the right headspace today to shoot,” and then we don’t shoot. (laughs)

But now it seems that you are going for experimentation more than anything. Why?

Jeanne Dielman by Chantal Akerman. That film has always stayed with me, and I really wanted to make a film where the narrative and the storytelling are very different from the standard: it’s not like Hollywood where it’s more about cause and effect, where it’s always about drama, and it’s Act One, Act Two, Act Three. This film is more about the process, the process of preparing a dinner for your dying mother, the same kind of dinner that she cooked for her family every year on New Year’s Eve.

So in that sense, food is pretty much the key element in those cultures. Also, my mother did not know how to show affection, so even later on when she was getting old, when I saw her, she would just shake my hand. That’s how she was brought up and that’s how she was. But she would make me these very special kinds of dumplings which I loved, which were very, very difficult and took a long time to make, but she made them because she knew that I really liked them. But meanwhile, she would only shake my hand. Towards the end of our relationship, we had nothing to say to each other, but there was a lot of emotion. I remember sitting in the courtyard where she sat in the sun when it was nice, and we just sat for an hour without saying anything. The silence was very, very emotional.

normal’>Crazy Rich Asians, The Farewell, they were romantic comedies that were quite good, but they are still in that sort of Hollywood mode. I would rather see more authentic Asian-Americans portrayed in a really realistic way, not in a way that tries to please an audience. That’s just me – I think it’s more important. I think the same thing with Black American films or Latino films, I think that I wish there were more films that were almost like authentic documentaries, but also interesting about the characters’ lives, that’s what people need to see and understand.

Maid in Manhattan, it’s about a Latina maid, Last Holiday was about a Black woman – it’s how I got boxed into working with ethnic leading ladies in romantic comedies, and that was the box that I got put in. I couldn’t get out of it at that time, so one of the ways was I just got out. I simply just got out of making the studio films that were out there after

John Wayne. And the interesting thing about my name is that I got my Chinese name first because you have to get the Chinese name so that it fits into the family tree and the family tradition of names. My father was King of the Forest so there was a theme of wood, my brother was Prince of the Forest, and I had to have a name that was part of the family tradition, so he found a word that means “the young bud,” the young beginning of a tree. That word sounds like Wayne. And so when he had to give me an English name, he said “Oh yeah, give him Wayne, because it sounds like a Chinese word too.” So that is how it came about. Maybe what is more influential is that when I was young, he used to take me to movies. And I just remember the experience of sitting there eating popcorn, which is sweet in Hong Kong, it’s not salty, and the lights go out and you sit there in the darkness and something comes on the screen and you begin to have a dream, so to speak, and that experience of movie going, that is why I love the cinema so much.

Smoke next to it, even though you have done so many films. What are your memories of your years with Paul Auster and making that special film and the other one, Blue in the Face?

The Joy Luck Club came out, which was the first film that was very popular to a wider audience. It goes back to not being boxed in with a stereotype because I knew that they would box me in with Asian-American films. So I jumped out of the box, and I made a film that’s really about Black and Jewish and Caucasians, who are separate and yet kind of connection as a family. I enjoyed working with Paul Auster, who walked with me all over Brooklyn to show me all the different places that he wrote about. I really enjoyed that kind of building process of understanding a place of culture and people. I made a very interesting film. It was a very difficult film, every actor in that film was difficult, but we made it. (laughs)