- Film

“Pauline at the Beach” by Éric Rohmer (1983)

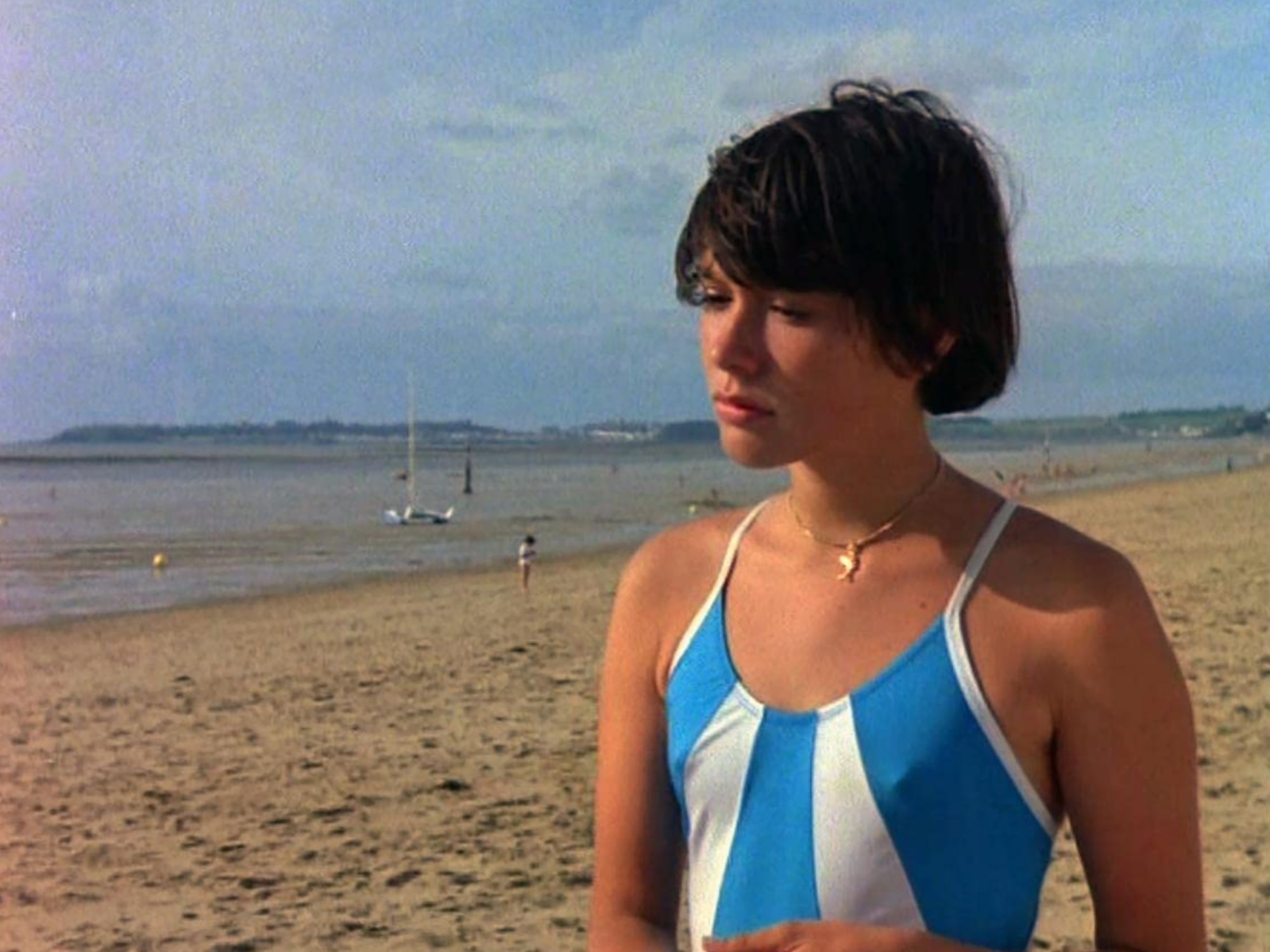

It is the end of summer in a quiet resort town on the Normandy coast. Fifteen-year-old Pauline (tomboyish brunette Amanda Langlet) and her elder cousin Marion (chic blonde Arielle Dombasle) are spending a few days in the family villa. On their agenda, besides swimming, windsurfing lessons and other holiday activities? As Marion puts it, the pressing subject of “that unpredictable thing called love.” Recently separated, she is ready to “be burned by desire and spark love in myself and in another, instantly and reciprocally.” The more levelheaded and mature Pauline is less specific in that domain, but not opposed to possibly finding a boyfriend.

On the beach, they meet Pierre (Pascal Greggory), Marion’s old flame still in love with her, who introduces them to Henri (Feodor Atkine), a divorced ethnologist. After an impromptu dinner, the adult trio embarks on a lively marivaudage, fueled by amusing banter and innuendos, revealing vastly different and contradictory opinions on, of course, love. It doesn’t take long for Marion to throw herself at Henri, (whose reciprocity is rather lukewarm), making Pierre jealous. Quietly observing the game playing, Pauline is flummoxed by the way relationships between men and women seem so unnecessarily complicated. Will it be the same between her and Sylvain (Simon de la Brosse), a local teenager that takes a liking to her?

The rest of the sojourn will see the protagonists navigate more or less successfully a turmoil of mixed feelings as they must confront several unexpected revelations, escalating amorous misunderstandings, jealousy and lies, to finally face reality.

Pauline at the Beach is Éric Rohmer’s third installment of his “Comédies and Proverbs” series.

An appropriate quote by the 12th Century poet Chrétien de Troyes set the tone in the opening credits: “Qui trop parole, il se mesfait”, which can be loosely translated as “A wagging tongue bites itself.” And indeed, the characters of the film never stop talking, a trademark of Rohmer’s style, in which verbal acrobatics and philosophical dialectics drive a clean narrative while exposing the characters’ navel-gazing tendencies to often comedic effect.

From his first opus released in 1962 to his last, 45 years later, Rohmer remained a fiercely original, independent and prolific author with films like The Collector, Claire’s Knee, My Night at Maud’s, and A Summer’s Tale. And a polarizing figure in French cinema, not unlike some of his New Wave colleagues, Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette.

He first wrote the outline of Pauline at the Beach with Brigitte Bardot in mind in the mid-1950s, as “the story of a young girl who takes her desires for reality,” a project that never materialized. But he thought it worth revisiting with an expanded and modernized plot to become more, as he explained, “a critical look of adolescence on adults who talk too much, and a way to show young people in the rare situation of being on the same basis as the adults.”

Prior to completing the script, he spent hours with his actors, recording some of their conversations which helped him flesh out the dialogues of the characters. Amanda Langlet recalled that “they talk about literature, poetry, music, never about movies …”

In 2019, during a Rohmer retrospective at the Cinémathèque Française in Paris nine years after his death, Arielle Dombasle, commented: “His strength comes from really observing the performers before they play the part, which he writes for them. He simply accentuates some traits. He already knows the actors well and he uses a little of their syntax, some of their mannerisms and idiosyncrasies, the way they speak. All his genius is there.”

For the actress, who had worked twice before with him in Perceval and The Good Marriage, Pauline at the Beach exemplifies “Rohmerian writing in all its splendor and a sunshine film by excellence.”

Rohmer told French critic Serge Daney, that he was extremely lucky with his actors. “The text that I have written suits them well. It’s particularly obvious in Pauline: they have been almost impregnated by the text. They have made it theirs. In fact, I don’t really work with them, and I have very little to do with that process. I think it is very important in cinema to trust the natural movement of things, without trying to interfere too much, to want to put too much in front of the camera, to direct too much and say too much.”

The filming of Pauline at the Beach took place in August 1982, entirely on location in Julouville, a quaint beach town, not far from the famous Mont Saint-Michel, in the Manche département, with a very small crew and a modest budget. Rohmer instructed his acclaimed longtime cinematographer, Nestor Almendros, to give a plain naturalistic look. As for the color palette, it was to be blue, white and red, inspired by some of Matisse’s paintings, more specifically the Romanian Blouse one, a poster of which is seen in Pauline’s room, colors that are also reflected in all the actors’ clothes. Cast and crew were lodged with locals and actors were forbidden to watch the dailies.

The film was poorly received by some French publications. The Figaro critic judged it “a strong contender for the most ridiculous film of the year.” Another felt that Dombasle had “nothing to show above her bikini.” But it nonetheless developed a cult following. In his New York Times review, Vincent Canby called it “a rare treat, […] effortlessly witty and incandescent.”

Interviewed by Dennis Hopper in 1994, Quentin Tarantino explained how, when working at Video Archives in Manhattan Beach in the late eighties, he felt compelled to “indoctrinate the customers on Éric Rohmer,” adding, “People would come to me with Pauline at the Beach because they had those sexy boxes, you know, and asked, ‘How is this?’ ‘Well, he is a director you have to get used to. The thing is, actually, I like his films … they are not dramas, they’re comedies but they are not really funny, all right? You watch them and they are just lightly amusing, you know? You might smile once in one hour, you know? But you have to see one of them, and if you like that one, then you should see the other ones, but you need to see one to see if you like it.”

Sound advice, still valid today for those willing to be introduced to one of the most original filmmakers.