- Industry

Docs: “Wuhan Wuhan” Puts a Human Face on the Pandemic’s First Months

The onslaught of COVID has already birthed a big surge of nonfiction cinematic pandemic offerings, and future waves are as reliably guaranteed as are real-world spikes in highly transmissible omicron offshoot variant infections. Many such films will, unfortunately, trade largely in carbon-copied tragedy, with only a few details changed.

But director Yung Chang’s meditative Wuhan Wuhan, executive produced by Donnie Yen and kicking off the 35th anniversary season of the award-winning series POV on PBS on July 11, has the stark benefit of a highly unique angle, unfolding as it does over a two-month period during February and March 2020, at the height of the COVID pandemic, in the very city where the pandemic first began. Free from voiceover or any editorializing, this highly observational documentary puts a humanizing spin on the early days of the virus, during which so much was still unknown, as Chinese frontline healthcare workers and infected citizens together grappled with fear over the invisible killer.

Wuhan Wuhan focuses predominantly on five engrossing and heart-wrenching narrative strands. Representing the backbone of the film is 30-year-old Yin, a furloughed factory worker originally from Xiaogan who throws himself into work as a volunteer medical driver, and his younger wife Xu, who is 37 weeks pregnant. Their relationship, and the full-on assault on Yin’s general optimism from his passengers, is in itself a fascinating little soap opera.

While a portion of the movie follows Yin around in his car, and details his domestic life, much of the rest of Wuhan Wuhan unfolds in and around Fangcang Temporary Hospital, a special COVID medical unit built inside a convention center to house and treat up to 2,000 people with mild-to-moderate symptoms stemming from infection.

There are a couple of supporting characters, including an angry, obstinate 57-year-old who is dubbed “Grandpa” Shen, but the film mostly focuses its attention on three medical professionals and one patient. These figures include Dr. Xiannian Zheng, a kindhearted doctor and ER chief who struggles with the inconsistent quality of PPE with which he and his team are being provided. “This pandemic is unprecedented. We don’t know much. We may make some mistakes. That’s life now,” he says with a shrug, acknowledging in resigned fashion his belief that medical professionals will bear the brunt of physical consequences as well as facing public fear and ire.

The other subjects are Susu Wang, an unflappable ICU nurse; Dr. Guiqing Zhang, a compassionate volunteer psychologist who tries to counsel scared citizens; and Xiuli Liu, a strong-willed mother who along with her nine-year-old son Lailai is stuck trying to navigate the Byzantine and ever-shifting system of healthcare regulations within China.

Canadian-born Chang (Up the Yangtze, China Heavyweight, This Is Not a Movie) is an internationally lauded filmmaker whose work is known in large part for highlighting those in rural areas and on the economic fringes of society. But while artistically Wuhan Wuhan exhibits many of the same qualities as those of his best work, there is also a bit of hollowness to its back-footed posing. There is one quick glimpse of some memorials to whistleblower doctor Li Wenliang, who was dominating Chinese social media at the time as a heroic truth-teller, but no one dares actually speak his name.

The involvement of action superstar Yen, a huge name in China, skews the perspective a bit, especially when combined with selective end-credit codas about the film’s featured characters, as well as information about the final Wuhan COVID tally (an official count of 50,008 cases and 2,574 deaths) that is presented without a critical eye. The film arguably strives to be apolitical, but these facts, while not quite serving as propaganda, have the unintended effect of at least glossily soft pitching the truth about the full efficacy of China’s draconian shutdown policies, all which, of course, flow from consolidated communist rule.

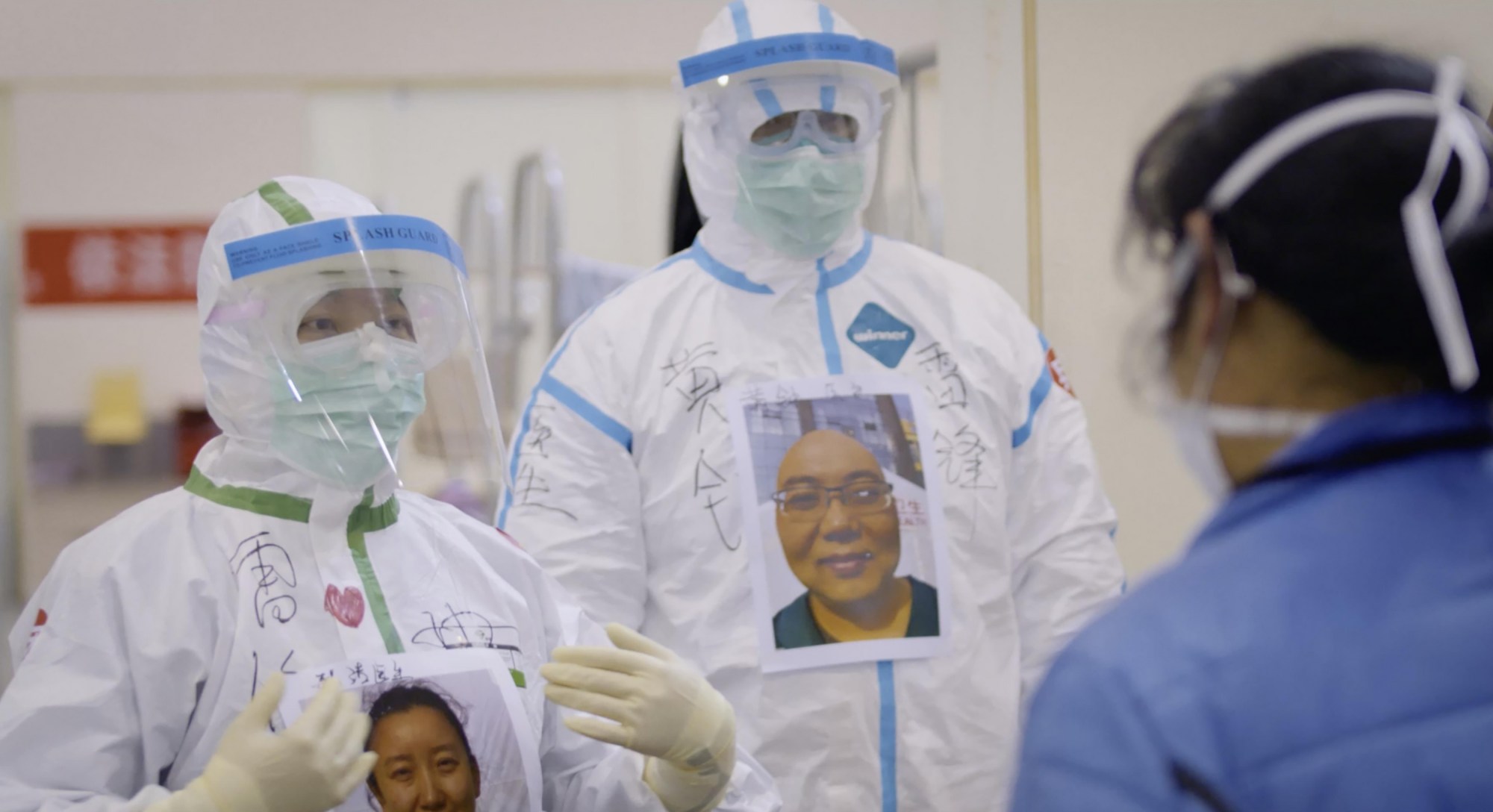

What helps Wuhan Wuhan overcome these eyebrow-raising qualities is the film’s location and its portrayal of very human breaking points (Yin and Xu’s fight over picking up a baby crib, for example; Xiuli falling apart after the effects of two negative tests are undone by another positive result, threatening to separate her from Lailai; a random woman crying over her husband’s death, asking why she survived and not him), as well as a couple of moments of rare levity. In an example of the latter, after some patients good-naturedly joke about not knowing what any of their doctors really look like, Zheng and others get large color photos taped to their chest.

The unhurried artfulness of Chang’s movie, whose technical package is superb, also recommends it. An original score by Hualun, a rock band from Wuhan, serves up metronomic rhythms in early passages, before giving way to more meditative patterns of synth and light percussion.

Some of the footage of the abandoned cityscape, including giant trucks spraying decontaminating mist, has an eerie quality that evokes post-apocalyptic genre films. But Chang and editors Zimo Huang and Evita Yuepu Zhou (who also deserve special mention for the manner in which they intercut between all of these stories) more frequently pull shock from unexpected places, as when Susu talks about passing out from exhaustion, or Yin casually mentions to a passenger about an elderly man jumping off the roof of his apartment building. Wuhan Wuhan is tragic, yes, but because of its time and place it’s also shot through with a pulse-quickening unknowingness, and in that setting, there’s a special quality to its depictions of grace and the unlikely hopefulness which springs forth.