- HFPA

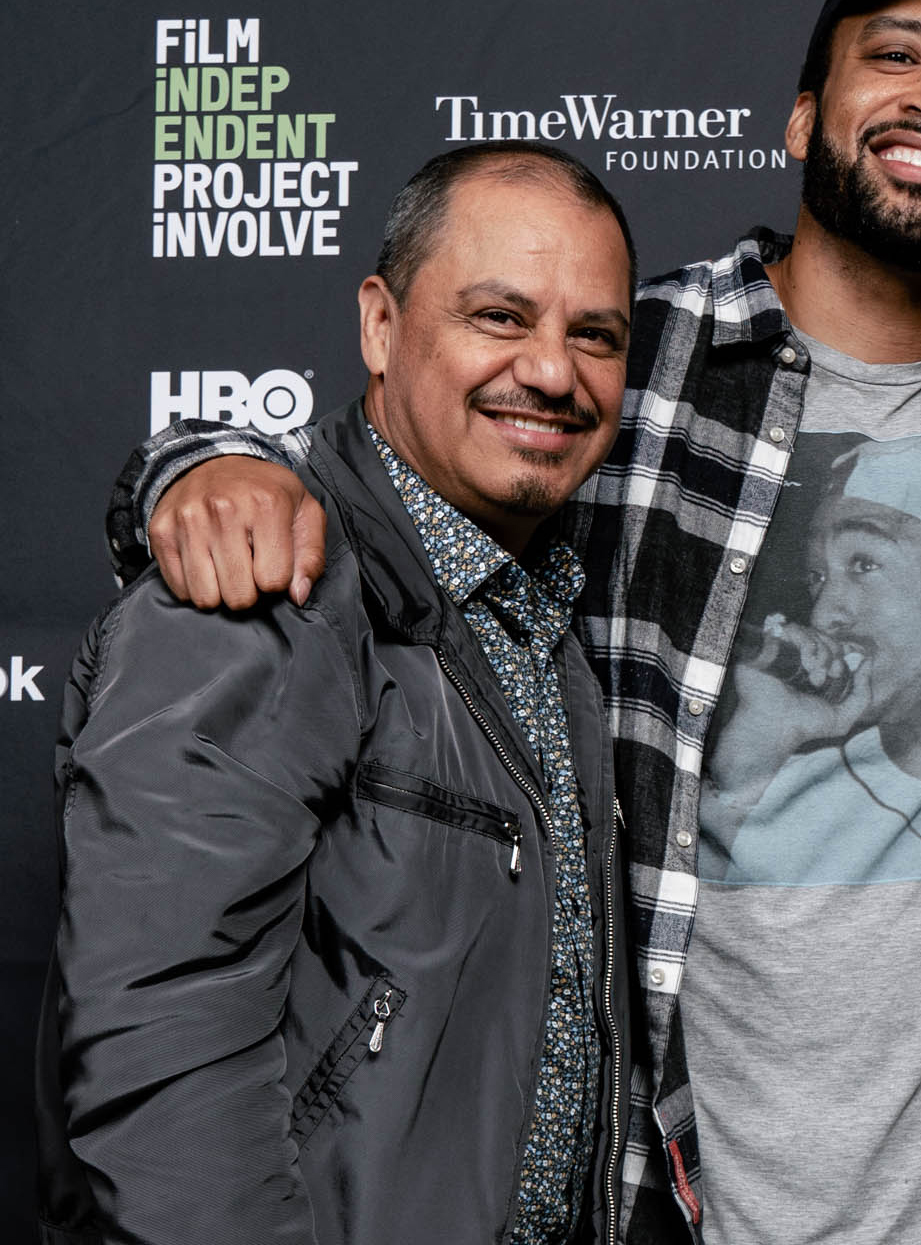

Doing the Work: Francisco Velasquez, Project Involve/Film Independent

Doing the Work is a series profiling key recipients of HFPA Philanthropy

Francisco Velasquez, the leader of Film Independent’s short film production program, has been a lover of film since childhood. A Mexican-born bicultural man, he grew up in Los Angeles with his family, watching “bad Mexican movies from the ‘70s and ‘80s” at the local drive-in while enjoying pan dulce and coffee, and big Hollywood productions every weekend at theaters downtown. In those early days, he could not help but compare the two types of film, fantasizing of ways he could improve the flaws of the Mexican ones if he were the director. Later on, he discovered that college didn’t have to be all drudgery. When a friend invited him to watch and discuss a film in class, he accepted willingly. It turned out that the film was Fellini’s 8 ½, one of his all-time favorites.

His baptism into world cinema enriched his studies in Latin American literature. “Any time I read a novel or a short story, I was seeing movies,” he said. He eased into filmmaking under the mentorship of avant-garde director Chick Strand and applied to the University of California Los Angeles for graduate film school. He was lucky to study along with such iconic creators as Patricia Cardoso and Alexander Payne, while his thesis film had a successful run at the New Directors New Films in New York. It was Cardoso that suggested he join Film Independent. Even though he resisted joining a group at first, he very quickly realized that the organization had a lot of insight to offer to young directors. After dabbling in freelancing, he jumped at the opportunity to apply for a leadership position at Film Independent’s Project Involve, where being a Latino gay filmmaker was seen as an advantage.

When he started his long tenure at Project Involve, the program did not include film production. He could tell the world how promising the participants were, but “wouldn’t it be better if I could say – here, watch this film?” This was the question that led naturally to the inclusion of the making of several short films every year at PI, from 2009 onward. And it seems that his vision of a culturally diverse, independent cinema has been gratified in the last decade.

“I think that cinema has always been a global product except that the dominance and the productivity of American cinema have been overwhelming,” he explained. Besides maybe the French, the Italian and the Japanese filmmakers, Hollywood has consistently presented superior production value. Subtitles don’t help either. For the longest time, everyone preferred to see the films that came out of the US “without even giving the chance to a good Iranian or Indian film”. Now, with the help of new technologies and the increased accessibility, it has become easier to see these films. Organizations like Film Independent have contributed to making world cinema more widely seen as well. Just recently, the Spirit Award-nominated Peruvian film Retablo was like a little revelation to Velasquez: “Oh, my God, that film was so beautiful, so nuanced, it made me cry … But if it had not been for [the Spirit Awards], I would not have come across this film”.

“This is the power of organizations like ours,” he pointed out; “to bring attention to films that reveal the humanity of people through storytelling. Through the stories of other people and other cultures, we find the common ground, that humanity that comes across from all over”. “When you see [a film] that impacts you, this is cinema – another dream, another reality,” he goes on with genuine enthusiasm; “this is what drives me, the emotional connection”. The same standard of films connecting with audiences is his measure for the success of the participants at Project Involve.

“I want our fellows to get themselves out there and connect with their audiences,” he stressed. Perhaps it is this direction set by Velasquez that gives an edge to the PI shorts, shorts with daring and personal stories that pose no qualms about pushing the edge. You can hear him talking to his mentees: “C’mon, you need to give me something that gets me here. It’s not about showmanship and camerawork, it’s about needing to feel something, to connect. Go for it, go for the kill! Don’t be afraid!”. As vehement as he may be with his fellows, he has no illusions about the immense difficulty of breaking the barrier of fear and realizes that “not yet having the courage to dig into my personal story” is what has so far kept him from developing his own projects. “Filmmakers like Barry Jenkins and Lulu Wang are brave and courageous because they bring themselves on the screen for us to connect and understand and empathize with,” he said. “I bow to them for their courage.”

Connecting with one’s own soul and confronting the deeply rooted hopes and fears is essential for a program that is “focused on underrepresented voices”. “Nothing against the tentpole films,” he went on. “We all like the Harry Potters of the world, the superhero films … But there is this otherness, this other world that has no ‘in’. So, if we want people to see our work, it has to be meaningful.” “For the most part,” he added, the fellows “have been prepared by some of the best [film education] programs around the world”. At Project Involve the emphasis is not on the artistry but on “getting to the voice, what will connect me to you”. About this point he is relentless. “Don’t give me superficial stuff. What is it that you really want to tell your audience? Take us there, so we can all understand!” The connection within, strangely, helps “the people who do not know your culture to empathize with it”. “That way,” he concluded, “we build community as well.

Community building is not so that a few people find solace in isolation but so that “we connect with the world”. “We are all human beings and all have emotions,” Velasquez reiterated. “If we took it from there, we wouldn’t be having this craziness of racism that we have now,” he mentioned, referring to the recent Black Lives Matter protests in the wake of the murder of George Floyd. “I think that films that make us connect help change the way we perceive other people, they humanize the ones we don’t know and get rid of our fear of the ‘other’.” For all these reasons, inclusion and diversity lie at the foundation of Film Independent in general and Project Involve in particular, and they constitute major criteria in admitting the PI fellows, a process that Velasquez compares to the assembly of a chocolate box: “All rich and delicious … all the flavors, and who doesn’t like chocolate?”.

Yet, how can these wonderful new filmmakers survive making their art if there is no paying audience? “You don’t only need to survive but you need money to make more movies; it’s a double whammy,” he said. “The key is in how you monetize the viewing through the media technology.” Now that anything is readily available to us at a click, the question is: How will the money reach the filmmaker? It is a puzzle that led Velasquez to think that Film Independent could fill the void by establishing an exhibition channel that favors the creators. “There are so many excellent films out there, and they need a house.”

But, who knows, the social distancing mandated by the pandemic may bring back the spirit of Cinema Paradiso. The resurgence of drive-in theaters could be accompanied by the return of open-air projection … That thought takes Francisco Velasquez back to his childhood when his very first cinematic experience took place on the wall of a yard. “I’m always an optimist,” he said smilingly. “Now that I’m a lot older, I see everything like waves, coming and going.” Ultimately, the whole reason he got into film is “the power of the image”. And that can never be taken away: “Just open the doors and let everybody tell their stories. I think that would make a better world”.