- Film

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies: Max Ophüls’ ‘Souvenirs’

It was August 1945 and in his two-story house on Whitley Terrace in the Hollywood Hills, Max Ophüls had started writing a personal bio at the request of a publicist for the company that had finally hired him after four years of unemployment. Like many of his European colleagues before him, the German-born and French-naturalized filmmaker had moved to America in 1941, hoping to find work in Tinseltown. But nothing had materialized until finally, his compatriot Robert Siodmak recommended him to Preston Sturges who had formed the independent production company California Pictures Corporation with Howard Hughes. Ophüls was to be paid a very modest, if not humiliating, $500 a week.

“Hollywood had been terribly fascinating, but my job stayed in a comatose state. I did not understand why in the world capital of cinema, no one thought of ending it for me. At last, thanks to Preston, I was finally going to be able to work and make films again,” he noted enthusiastically, in conclusion, of what would be become Souvenirs, a lively account of his life from his birth in Saarbrucken in 1902 to his Hollywood exile, and published for the first time in France in 1963 and never translated in English. The text was accompanied by a lengthy interview that Ophüls gave to François Truffaut and Jacques Rivette a few months before his death in March 1957.

The interview serves as an enlightening addition that gives more insight into the working mind of one of the most unique filmmakers whose films often displayed the masterful use of sweeping crane and dolly movements and dazzling tracking-shots. The sensual arabesques of his camera always part of the story and at the service of the actors in a trademark idiosyncratic style. Never better illustrated than in his masterpiece, the 1952 The Earrings of Madame de…starring his favorite actress Danielle Darrieux along with Charles Boyer and Vittorio de Sica.

Ophuls directing James Mason and Barbara Bel Geddes on the set of Caught, 1949.

slim aarons/getty images

As a teenager, Maximilian Oppenheimer was determined not to go into the family textile business. One day in 1919, he told his father that he wanted to become an actor. But not that one of the reasons was to meet girls! And in case he would be an embarrassment, “he forbade me to use his last name.” Under his new patronym, he found work in the theater, all over Germany where he also directed several dozen plays. “Except the Chaplin comedies”, he admits, “I must confess no other film really interested me and anyway. I considered cinema as a threat to the future of theater and, after all, theater was all my life.” But to Truffaut and Rivette, he admitted that he liked several of Fritz Lang’s silent films, and was a fan of F.W. Murnau, especially his Faust. “I was always attracted by films that had nothing to do with naturalism.”

After seeing his first talking picture in 1929, he had an epiphany. “Suddenly I did not see the enemy of the theater anymore but its natural continuation. At this precise instant, I wanted to leave for Berlin to make films.” There, in 1931, he directed his first film for UFA, at the time the biggest movie studio in Europe, and to which he insists paying tribute to in his Souvenirs, still grateful for the chance he was given. “Today,” he remarks, somehow provocatively, “many of the exiled filmmakers in Hollywood pretend to have forgotten about that great studio that helped them get their start. A German company! Therefore, they don’t want to remember. Well, as for me, I insist in congratulating UFA, in the name of all the directors, camera operators, designers, screenwriters and musicians who made it here, many of whom are my neighbors today.”

Other films followed, most notably Libelei in 1932, released just before he escaped to Paris after the February 23rd Reichstag fire a year later. Leaving the newly bought villa on the Lietzensee with a one-way train ticket for his wife Hilde and son Marcel (who would later direct the groundbreaking documentary The Sorrow and the Pity), and a few suitcases. One of many geographic detours he endured, each time with equal resilience. “All came up so quickly and in depressing matter. Our emigration was far from heroic. Out of modesty and by fatalism, I had not made contact with the French cinema community.”

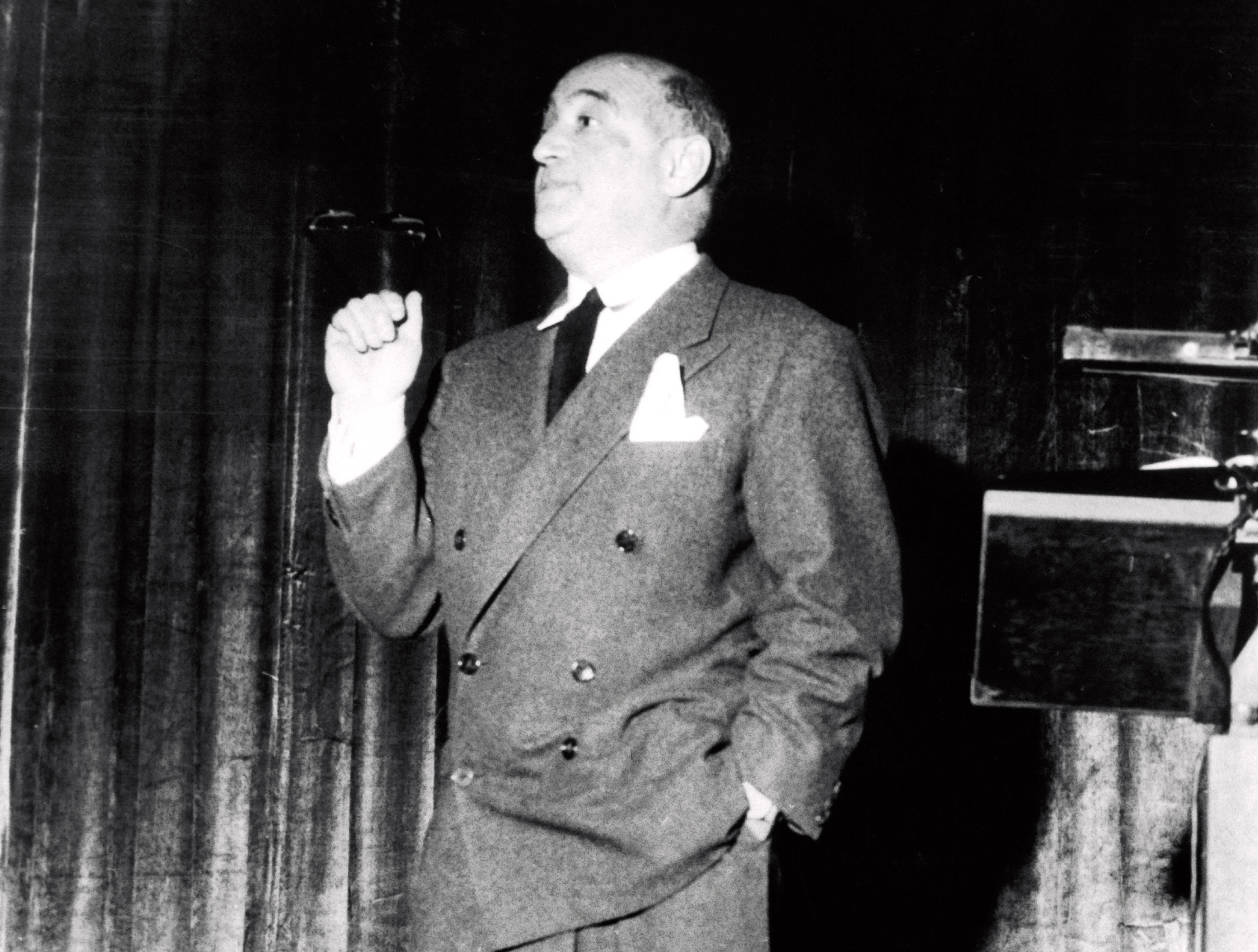

On the set of La Ronde, 1950.

gamma-keystone/getty

Nonetheless, he quickly found work even though he had to familiarize himself with the new methods. He could not be too picky in what he was offered so he found himself working in Italy and Holland. “All those years, I was not able to choose my projects.” Once in Hollywood, he tried to find a niche. As his wife would comment later, “Max was so stunned by all the technical possibilities offered by the studios, that his admiration risked putting his artistic judgment in peril.”

He enjoyed working with Douglas Fairbanks Jr. in the romantic adventure The Exile (1947). “It is while making this film with great freedom, that I started to like Hollywood. I was not prejudiced against Hollywood, but when you are unable to work, one doesn’t like the place or the country you live in.”

He followed with Letter from an Unknown Woman starring Joan Fontaine and Louis Jourdan. There was a change of style for the last films he made, more in a film noir vein. Caught and The Reckless Moment, both starring James Mason with whom an enduring friendship would last for the rest of his life.

He returned to France in 1949 where he would make four more features starting with La Ronde where Anton Walbrook as the master of ceremony wistfully confesses: “I adore the past. It is so much more comforting than the present and more certain than the future…” Something, one can imagine Ophüls himself saying.

Written with self-deprecating humor, Souvenirs is laced with ironic remarks and details of his many professional struggles, assorted setbacks, financial difficulties, and abandoned projects, one being an adaptation of Honoré de Balzac’s La Duchesse de Langeais that Greta Garbo wanted to do. One ultimate disappointment was the crushing flop of the flamboyantly baroque Lola Montes, his last film and the only one in color, mutilated against his will after its December 1955 release.

In the conclusion of his conversation with Truffaut and Rivette, Ophüls talks extensively about a worrisome trend that he foresees as inevitable: consumerism affecting the behavior of film audiences more and more. “They don’t have any aesthetic patience anymore. The danger is that you see too many films. Something that doesn’t affect me since I have found a new excuse not to go to movies too often! In the case of a film made by a director you deeply admire, you can easily imagine it and you almost don’t need to see it: when you are familiar with the particular kind of writing of a great filmmaker, you are prone to know what to expect. As for the bad ones, it is the same.”