- Industry

Out of the Vaults: The Breaking Point (1950)

When Eddie Muller, president of the Film Noir Foundation, introduced a screening of The Breaking Point on TCM, he told the story of Ernest Hemingway and director Howard Hawks on a fishing trip in 1939 when Hawks told Hemingway he could make a decent movie from his worst book. When Hemingway asked him which book that would be, Hawks answered, “That piece of junk, To Have and Have Not.” Hawks did make the movie in 1944 with Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall in her debut performance, but Hemingway would be forgiven if he didn’t recognize his story onscreen – aside from the title and the protagonist’s name, the film had nothing to do with the book.

1950’s The Breaking Point, however, is faithful to Hemingway’s book, using a different title as Hawks had already used To Have and Have Not. This version was directed by Michael Curtiz, specifically requested by star John Garfield who got the lead role of Harry Morgan, a WWII veteran scratching out a living in Balboa Island (the location was moved from Key West) as the owner of a boat he charters out to fishermen and tourists. Curtiz had been responsible for Garfield’s debut in Four Daughters in 1938 and had gone on to great success with Casablanca in 1942 and White Christmas in 1954, among many others. Garfield, who had left Warner Bros. to form an independent production company, had found his career on the downswing. This was his return to WB and an attempt to regain his former popularity.

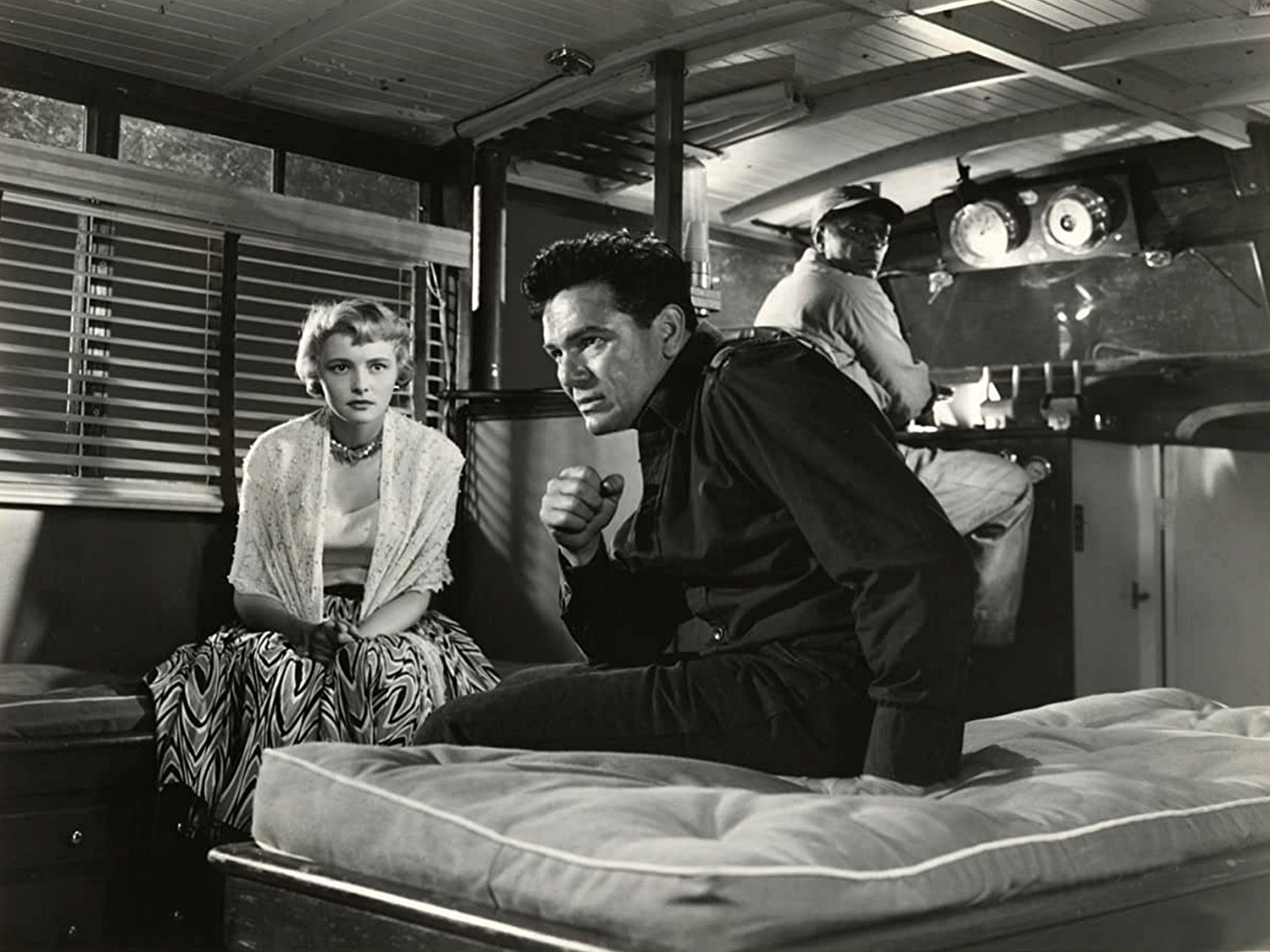

In the story, Harry needs money desperately to support his wife (played by Phyllis Thaxter) and two little girls. He agrees to take a client and his mistress Leona (Patricia Neal) to Mexico where the man skips out on him without paying, leaving Harry to fend off Leona’s advances and figure out how to get home. An encounter with a shady lawyer called F.R. Duncan (Wallace Ford) who offers him a deal to smuggle some Chinese immigrants into the US ends badly. Then the Coast Guard impounds his boat. Increasingly frantic because of the huge debt he still carries on the boat, Harry takes up Duncan’s offer of another dubious deal when Duncan gets him his boat back. This time he is the getaway driver for a gang of thieves. Once again, things go sideways ending in a spectacular gunfight on the boat.

The Breaking Point is film noir at its best, with outstanding performances by the cast, especially Thaxter’s in the less glamorous role as Harry’s wife. Despite having to keep the family together on a shoestring and the stubbornness of her husband who refuses to find other work, their domestic scenes together show a chemistry and even a sensuality that is unusual for the era. “I can think about you any time and get excited,” she tells him. There is one heartrending scene in which she dyes her hair blond just like Leona’s to appeal to Harry. He is stunned and stammering; her humiliation is complete.

Garfield always maintained that this was his favorite performance, and indeed he makes the most of the charismatic but broken captain who makes terrible choices for the right reasons, struggling to adjust to a post-war world. Neal is the quintessential femme fatale, probably the most beautiful one in all of film noir, a character not in the novel. But the heart of the film is Juano Fernandez’s character Wesley Park, a Black man, and Harry’s first mate and friend. A composite character from Hemingway’s novel, the film eschews the novel’s casual racism and turns Wesley into a dignified and faithful friend at a time when the South was still segregated. The Breaking Point has one of the best last shots of any film – a visual of one person whose life has shattered through no fault of his own alone and bewildered – it lacerates your heart and makes you forget to breathe. There is no question the movie is better than the book. Hemingway himself said it was the best adaptation of any of his books. The film’s poster is headlined by “Screaming off the pages of the Hemingway story!!”

The Breaking Point never got the credit it deserved when it was released. Garfield’s name had appeared on a list of communist sympathizers because his wife Roberta Seidman had been a member of the Communist party. Garfield was summoned to testify before the U.S. Congressional House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) and refused to name names. His career effectively ended. Jack L. Warner would not publicize the movie and there would be no more movie offers for Garfield. Despite excellent reviews, The Breaking Point faded. Garfield would make one more movie after this which he produced himself; he died of a heart attack in 1952 at age 39.

Warner Bros. worked with YCM Laboratories to restore The Breaking Point, and Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation provided an additional set of preservation elements for deposit at the UCLA Film & Television Archive. The new elements consist of a duplicate picture negative made from Warner’s fine-grain master positive, a duplicate track negative made from Warner’s track positive, a composite print made from the new duplicate picture and track negatives, and an answer print from the original nitrate picture and track negatives.

Preservation funding was provided by Warner Bros., the Hollywood Foreign Press Association, and The Film Foundation.