- Industry

The Prevalence of “True” Stories

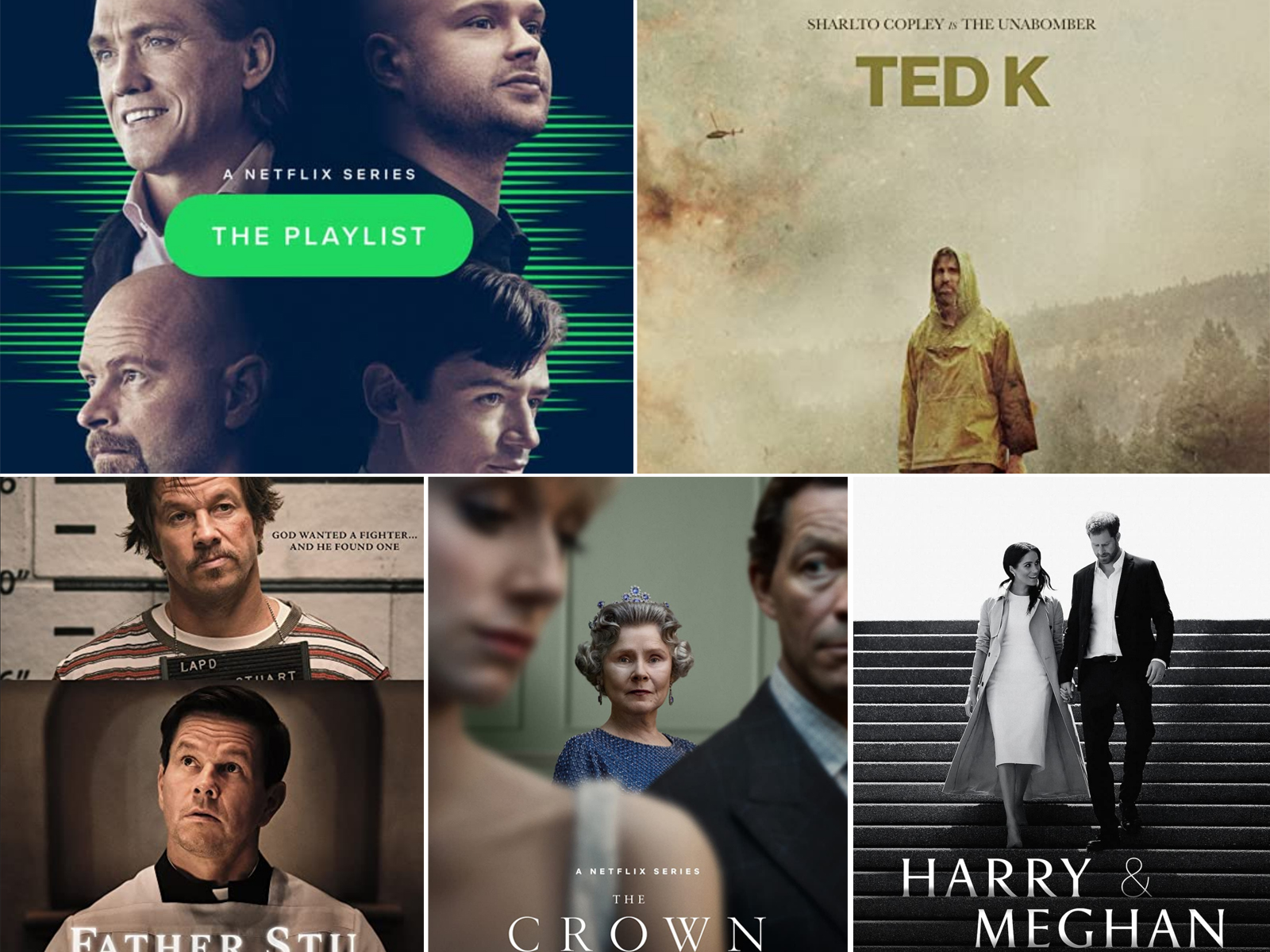

Casual channel zapping lets you follow the labor pains of the music streamer Spotify (The Playlist), or lets you get into the conflicted mind of the “Unabomber” Ted Kaczynski (Ted K), or lets you observe a boxer named Stuart Long changing his work clothes as he becomes a fighter for God (Father Stu), or lets you get a glimpse into the histrionic insularity of the British Royals (The Crown) and their offspring’s revelations (Harry & Meghan).

Stories of real people’s lives and actual historical events are ubiquitous and it seems they are more numerous than ever. Sure, the reliving of a memorable past has been around since the time when early men scratched scenes from a real hunt on the wall of their cave. And that urge to re-imagine what once was real continued on painters’ canvases all the way to the big and small screens of today.

“Never before have dramatizations of well-known people and events been so popular and prevalent,” stated the New York Times recently. And the nominations for this year’s 80th Golden Globe Awards prove how unusually valued and immensely attractive reality-based stories are at present.

About half the film and TV titles in all categories, including the titles that led to the nominations for filmmakers and actors, were “based on or inspired by a true story or true event.”

There are, of course, Steven Spielberg’s musings about his formative years in The Fabelmans. He reveals intimate memories and moments of wonder, of sadness and youthful exuberance with such personal candor that one might wonder why the movie is not called “The Spielbergs.”

The glamorous and tragic lives of Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe have been retold over and over again on film. No exception this year: there was Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis with Austin Butler as the Rock Icon and Blonde with Ana de Armas as the immortal Ms. Monroe.

Other featured celebrities in miniseries are Pamela Anderson and Tommy Lee in Pam & Tommy and Michael Shannon as George Jones and Jessica Chastain as Tammy Wynette in George & Tammy.

Celebrities of a different kind were also the subject of popular TV productions such as the horrific world of serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer retold in Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story.

“Based on the Unthinkable True Story” is the film The Good Nurse. Jessica Chastain and Eddie Redmayne play night shift nurses in a hospital whose friendship becomes severely estranged after a series of unexplained deaths among the patients.

The miniseries Under the Banner of Heaven is the adaption of a book by Jon Krakauer who researched the real-life 1984 murders of Brenda Wright Lafferty and her 15-month-old daughter Erica Lafferty within the fringes of the Mormon church.

The Inspection is the biographical account of a marine who feels he is forced to hide his sexual orientation. Viola Davis is The Woman King in the film based on a historical female ruler in the Kingdom of Dahomey, a powerful state in Africa during the 18th and 19th centuries.

A drama of more recent history is the subject of the film She Said. A journalist, played by the Globel-nominated Carey Mulligan, starts the Me/Too movement with her exposure of Harvey Weinstein.

And even the winner in the category Non-English Language Films has a very real political background, the seemingly unwinnable struggle of a group of lawyers against Argentina’s bloody military dictatorship in Argentina, 1985.

“The entertainment genre of historical drama is flourishing,” said the New York Times, but so are the limitations and legal implications of “true” stories, especially when real living people are involved. There is the protection of the First Amendment. But disclaimers like “based on a true story” are used as additional shields against possible lawsuits.

The network behind one of the Golden Globe nominees went even a step further: the limited series Inventing Anna, created by Shonda Rhimes, introduced us to the alleged schemes of a real-life con artist tricking New York’s Party People. In the spirit of the hilarious subject, each episode opens with the credit: “This whole story is completely true. Except for the parts that are totally made up.”