- Industry

Racist Hollywood: Hollywood’s Disgraceful Past

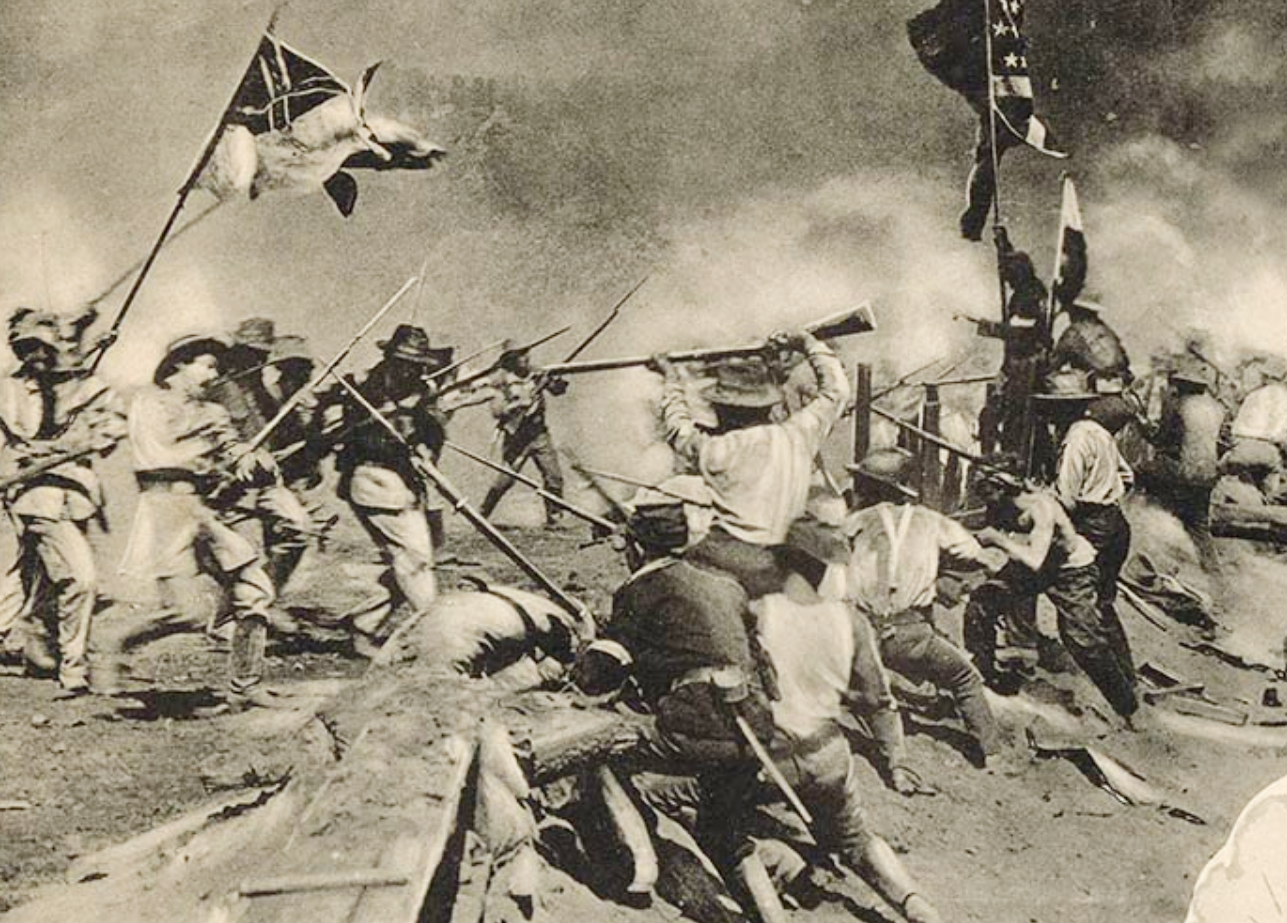

The silent film era, which lasted from the 1890s to the 1920s, was run by white men. Any Black performers seen in the films were portrayed through the white perspective and confirmed stereotypes that abounded at the time. Black characters were depicted as clowns and servants at best, sexual predators at worst, most egregiously in D.W. Griffiths’ The Birth of a Nation in 1915. Many of the white actors were in blackface portraying African Americans, while the Ku Klux Klan were the heroes protecting American values and upholding white supremacy.

Richard Corliss, writing in Time magazine in 2002, explained the impact of the film this way: “The acclaim of Griffith’s masterwork made his virulent, derisive depiction of Blacks all the more toxic — indeed, potentially epidemic. This was not simply a racist film; it was one whose brilliant storytelling technique lent plausibility and poignancy to images of crude Negroes in the Reconstruction Senate, and of a Black man pursuing a white woman until to save her virginity, she throws herself off a cliff. Viewers could believe that what they saw was not only historically but emotionally true. Birth not only taught moviegoers how to react to film narrative but what to think about Blacks — and, in the climactic ride of hooded horsemen to avenge their honor, what to do to them. The movie stoked Black riots in Northern cities, and by stirring bitter memories in the white South, it helped revive the dormant Ku Klux Klan.” The film sparked bitter protests by the Black community. The NAACP sought, unsuccessfully, to have the movie banned.

The backlash from the Black community gave rise to the ‘race film’ industry when Blacks seized the opportunity to tell their own stories, produce films and direct them, even setting up their own companies to do so. The first Black film company was set up by William D. Foster in 1910 before Birth was made. The Photoplay Company’s The Railroad Porter (1912) is supposed to be the first silent film with an all-Black cast and director. The company didn’t last long but its purpose to change the audience’s perception of Black people was carried on by other Black entrepreneurs.

In 1916, the Lincoln Motion Picture Company was founded by brothers Noble and George Johnson. The company was even incorporated in 1917. Completely Black-run, its first film, now lost, was the two-reeler The Realization of a Negro’s Ambition, in 1916. It was directed by Harry A. Gant with ‘an all-star Negro cast.’ The story is about a Black man who rescues the daughter of a wealthy white oilman and becomes successful in the oil business. The company made five films in all, but they did not cross over to white audiences and were only shown in Black churches and schools. Its last film, By Right of Birth in 1921, was written by a woman, Dora Mitchell. It was shown at the Trinity Auditorium in downtown Los Angeles for two evenings, both sold out. The company folded soon after. Four minutes of that film are all that’s left.

The standout name of this era was entrepreneur Oscar Micheaux, an author, producer, and director of both silent and sound films. He was born in 1884 to a father who was born a slave. After struggling as a shoeshine boy and Pullman porter, he moved to South Dakota to work as a homesteader, chronicling that life in newspaper articles. He wrote several books. His autobiographical The Homesteader got the attention of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company. Negotiations fell through when the Johnsons wouldn’t let Micheaux direct it, so Micheaux set up his own company and made the film in 1918. It would be the first of 40 productions, met with tremendous success and making Micheaux the premier African American filmmaker of the first half of the 20th Century. He was very savvy in marketing. Advertised his stars as ‘the Black Valentino’ and the ‘sepia Mae West.’

His second film, Within Our Gates (1920) was an answer to Birth of a Nation. It depicts lynching, mixed-race ancestry, the Klan, the Jim Crow years, and the rise of the ‘new Negro,’ the one who would not submit to segregation laws.

While Micheaux was criticized by some for his melodramatic plots and films made on the cheap, he defended himself by saying “My results … might have been narrow at times, due perhaps to certain limited situations, which I endeavored to portray, but in those limited situations the truth was the predominant characteristic. It is only by presenting those portions of the race portrayed in my pictures, in the light and background of their true state, that we can raise our people to greater heights.”

Singer, actor and activist Paul Robeson starred in Micheaux’s third film, Body and Soul (1925). Roberson played the dual roles of a predatory preacher and his virtuous twin brother, giving rise to much controversy as it depicted a Black man as a rapist. Micheaux was denied an exhibition license from the Motion Picture Commission of the State of New York because it was deemed ‘immoral’ and ‘sacrilegious.’ He had to edit it down from nine reels to five before he was allowed to exhibit the work.

The Colored Players Film Corporation of Philadelphia was established in 1926 by Black vaudevillian Sherman Dudley and theater owner David Starkman, a white man. They made three-race films, most predominantly The Scar of Shame, released in 1929 with an all-Black cast and targeted to the Black audience. Produced and written by Starkman, the silent melodrama starred Lucia Lynn Moses, a Cotton Club showgirl. The film deals with class differences within the Black community. It made money but the company folded soon after. Moses’ sister, Ethel, was an actress known as the ‘black Jean Harlow.’ She too worked in Micheaux’s films such as Temptation (1936), Underworld (1937), and God’s Stepchildren (1937). She too had started her career at the Cotton Club before moving on to Broadway and getting in the film business.

A leading man of the era was Bert Williams, the Bahamian Black entertainer who started on the vaudeville circuit. A comedian and a best-selling recording artist, he was the first Black man to have a leading role on Broadway and the first to lead a film as well, Darktown Jubilee in 1914. W.C. Fields called him “the funniest man I ever saw — and the saddest man I ever knew.” He and his partner George Walker had a show that they performed in blackface and called themselves ‘Two Real Coons’ to distinguish themselves from the white actors who performed in blackface. He appeared in Ziegfeld’s Follies several times. Footage of a comedy film Lime Kiln Field Day, in which he was featured, was found by MOMA and restored in 2014. It had an all-Black cast.

Spencer Williams, Jr., best known for playing Andy Brown in the TV series Amos ‘n’ Andy, was another successful writer and director of race films. Starting his career in Hollywood as a sound technician, he wrote a series of shorts for producer Al Christie and produced the first Black talkie, The Melancholy Dame. After appearing in several Black westerns as an actor, he wrote and directed Son of Ingagi. The success was such that he was hired by a producer of race films who also owned a chain of theaters, Alfred N. Sack. The faith-based fantasy The Blood of Jesus, released in 1940 and celebrated for its portrayal of religious life in the South, was inducted into the National Registry of Films in 1991.

A special mention must be made of Siren of the Tropics, the 1927 French silent movie starring chanteuse Josephine Baker, the first Black leading lady in a major film. She played a West Indian girl involved in a romance with a French man. The movie was directed by Mario Nalpas and Henri Etievant and was a huge success in Europe. Baker would go on to make two more films: Zouzou (1934) and Princesse Tam-Tam (1935).

More than 80% of race films are lost, unfortunately, but a website and database set up by UCLA students, “Early African American Film: Reconstructing the History of Silent Race Films, 1909-1930,” keeps an account of Black performers and filmmakers in race films. The list has 759 names in all, so far, as well as the 303 silent films the researchers have managed to track down.