- Film

Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898-1971 – A New Exhibition Completes a Historic Narrative

“I was blown away at how thoughtful this museum, still even under construction, was approaching its content and how committed it was and it still is to expanding public understanding of film history,” says Jacqueline Stewart, Director and President of the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, in a recent press preview of its exhibition, Regeneration: Black Cinema, 1898-1971.

Five years ago, she had been invited to participate in the Regeneration Advisory Committee of the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles. An exhibition focused on the remarkably silent history of the birth of Black cinema – and its long connections with entertainment in general – was being planned for the future institution.

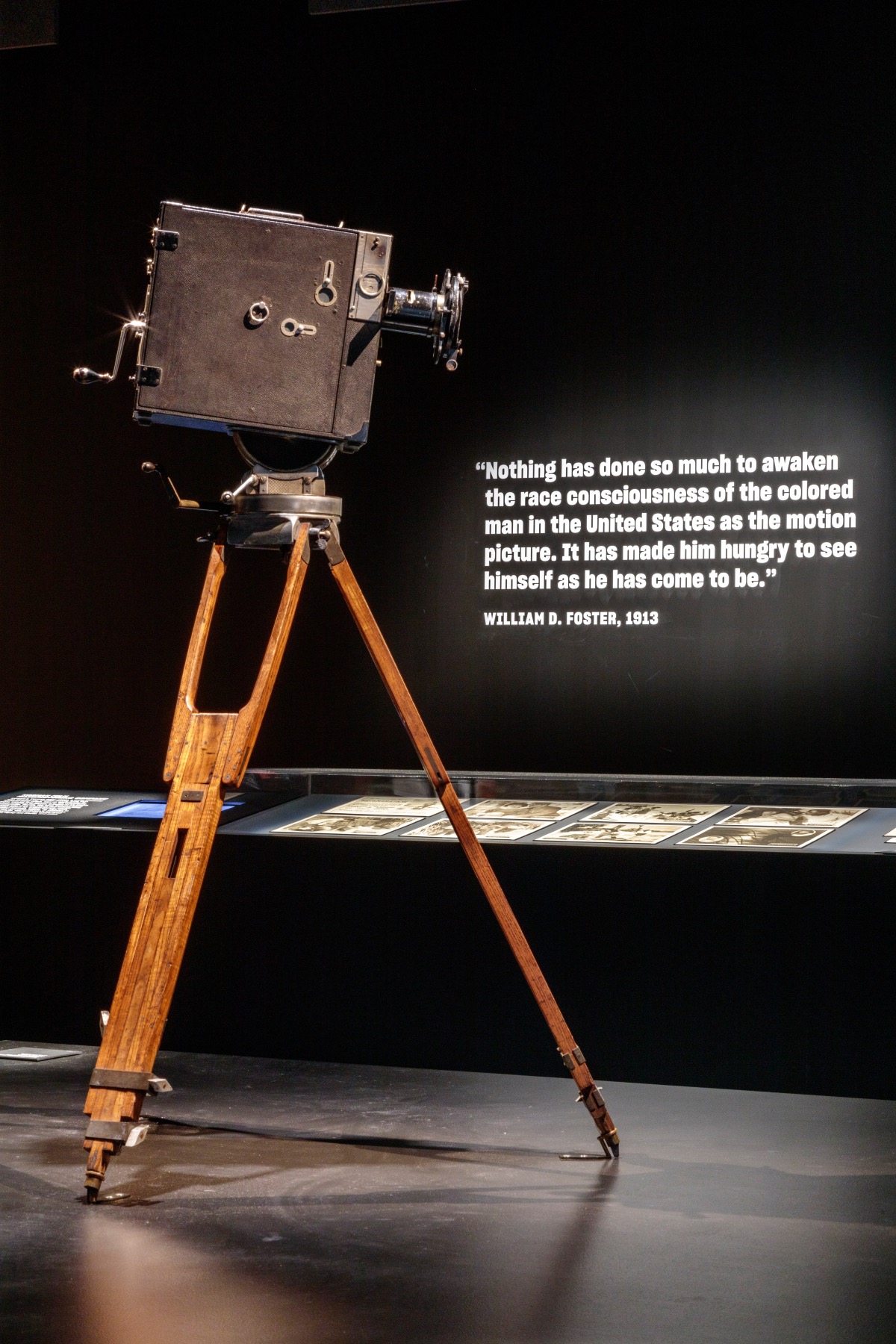

Now on its first year in activity, the Academy Museum opens to the public the exhibition, a unique and well-needed journey into the roots and the evolution of Black cinema and its journey through the ages, from segregation to independent movies, musicals, stars, and “soundies”, short musical clips made to be seen in cinematic jukeboxes in the 1930s and 40s.

“We are honored to offer the long and under-appreciated tradition of Black cinema in this country,” Stewart announces. “For a long time, the early days of Black history were sidelined. Scholarship in this area was largely unknown to most film fans. Now, it is our galleries that are telling the in-depth stories of the history, for all to see, study and admire.”

Planned and created by a group of six specialists and dozens of advisories and researchers, Regeneration follows the first years of Black movies within the history of cinema itself.

Regeneration is a journey through the evolution of Black cinema through seven galleries covering how social and cultural elements are shaped in images, clips of films, music, objects, and clothes.

The exhibition’s highlights include an opening with the first Black movie ever found, the short Something Good-Negro Kiss from 1898; galleries covering 1897 to 1915, when Black artists explored the new medium; 1910 to the 1940s, when segregation created two streams of movies – one of them, the “race films” exclusively for Black audiences by mostly Black filmmakers and actors; the impact of the Second World War and the dawn of the Civil Rights Movement on the inclusion of Black talent in studios and the industry at large; and the dawn of the new post-war generation of young, bold Black filmmakers.

The three-channel installation, Baltimore, by Isaac Julien from 2003, an homage to “Blaxploitation” recreated in the streets of Baltimore, runs in a dedicated gallery.

“(Co-curator) Doris (Berger) and I have been working steadfastly for more than five years,” points out co-curator Rhea Combs, Director of Curatorial Affairs of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery.

“Researching, conceptualizing, organizing this exhibition, working closely with film, object, and textile conservators in order to assemble everything that you now see. We wanted to document and explore the contributions of Black film artists in both independent productions, the so-called race films made by Black producers for Black audiences, and in mainstream American cinema.

“We lead with a clip from a recently discovered film and we end with 1971. Because it was a turning point in Black political resistance in this country and in this cinema, marked by the release of Melvin Van Peebles’ independent production, Sweet Sweetback’s Badass Song, that later became commonly identified as Blaxploitation.”

The clip that serves as the entrance to the journey of the first years of Black cinema, Something Good-Negro Kiss, had been a special discovery – the team discerned not one but two versions of the short, one print in the US and one in Norway.

The clip showcases two vaudeville stars of the late 19th century, Saint Suttle and Gertie Brown, ‘smarty dressed and having a laugh,’ in Rhea Combs’ words. (The short) becomes the first recorded example of intimacy on screen. “It also runs counter to many mainstream images of Black people at the time, too often pejorative, in one-sided, stereotypical portrayals,” Combs adds,

From pioneers like Oscar Micheaux and Josephine Baker to Hollywood stars like Lena Horne, Dorothy Dandridge, Sidney Poitier, Hattie McDonald, Harry Belafonte, Ossie Davis, and Sammy Davis Jr, Regeneration offers an important piece of the vast history of cinema, complete with a series of film screenings, a curriculum for high school students and, in February, a two-day Summit for artists, scholars, and filmmakers,

Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898-1971 opens on August 21, 2022, and runs until April 9, 2023.