- Festivals

Sundance 2021: Summer of Soul

Winner of the 2021 Sundance Documentary competition, Summer of Soul, can perhaps best be described as an engrossing history lesson with an irresistible beat. The documentary marks the directing debut of Ahmir Questlove Thompson and it takes us back to the torrid summer of 1969, when a public concert series, collectively dubbed the Harlem Cultural Festival, took place in Harlem’s Mount Morris Park. The concerts brought together an incredible lineup of predominantly African American talent and were filmed by Hal Tulchin, only to be eclipsed by that other concert which took place that very August a hundred miles due north, outside the village of Woodstock. That larger than life musical event obscured the Summer of Soul which was consigned to oblivion – until the filmmakers came across 40 hours of unedited film that had been stored in a basement.

The film has the live musical power of precedents like Dave Chapelle’s Block Party (2005) and the transcendence of the Aretha Franklin concert movie Amazing Grace. But in this case, the film also amounts to an invaluable document of pop-archaeology and even more, a record of a crucial moment in the nation’s cultural history. That summer of ’69 was the apex of the Anti-War and Black Consciousness movements (the story of Fred Hampton, the young and charismatic Black Panther leader who would be murdered in Chicago by the FBI only weeks after the festival, was coincidentally told in another Sundance film: Judas and the Black Messiah). The country seemed at an inflection point, deeply divided and roiled still by the recent assassinations of Malcolm X, Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King. In the words of the anthem sung in the film by the 5th Dimension, the dawning of the Age of Aquarius was upon the land. Organized by promoter Tony Lawrence, the concerts were meant to channel the righteous anger seething in many Black communities in a cultural event. They ended up recording a picture of Black American culture’s coming of political age as expressed through music.

The performances reassembled by Questlove in glorious 4:3 ratio, and complemented by interviews with many who attended and played at the festival, are a testament to what Cornel West called the unifying, regenerative and transformative power of Black music. They run the gamut from BB King’s blues guitar stylings to Mahalia Jackson’s Gospel hymns to the pioneering jazz of drummer Max Roach and his wife Abbey Lincoln. Sly and the Family Stone’s “psychedelic R&B” (the only band here which also played Woodstock), as well as more traditional Motown, acts like Gladys Knight and the Pips are featured and so are prominent Afro-Cuban innovators Mongo Santamaria and Ray Barretto. As integral to the film as the famous names that parade on stage are the faces in the crowd: from regular neighborhood folks to Harlem sophisticates and Black power militants, families and young people coming together in a moment of palpable community and Black cultural ownership. “As Black people, we didn’t know no therapist,” says Al Sharpton, among the interviewees. “But we knew Mahalia.” And when Ms. Jackson and Mavis Staple intone a rousing rendition of “Precious Lord”, it’s nothing short of a moment of collective healing.

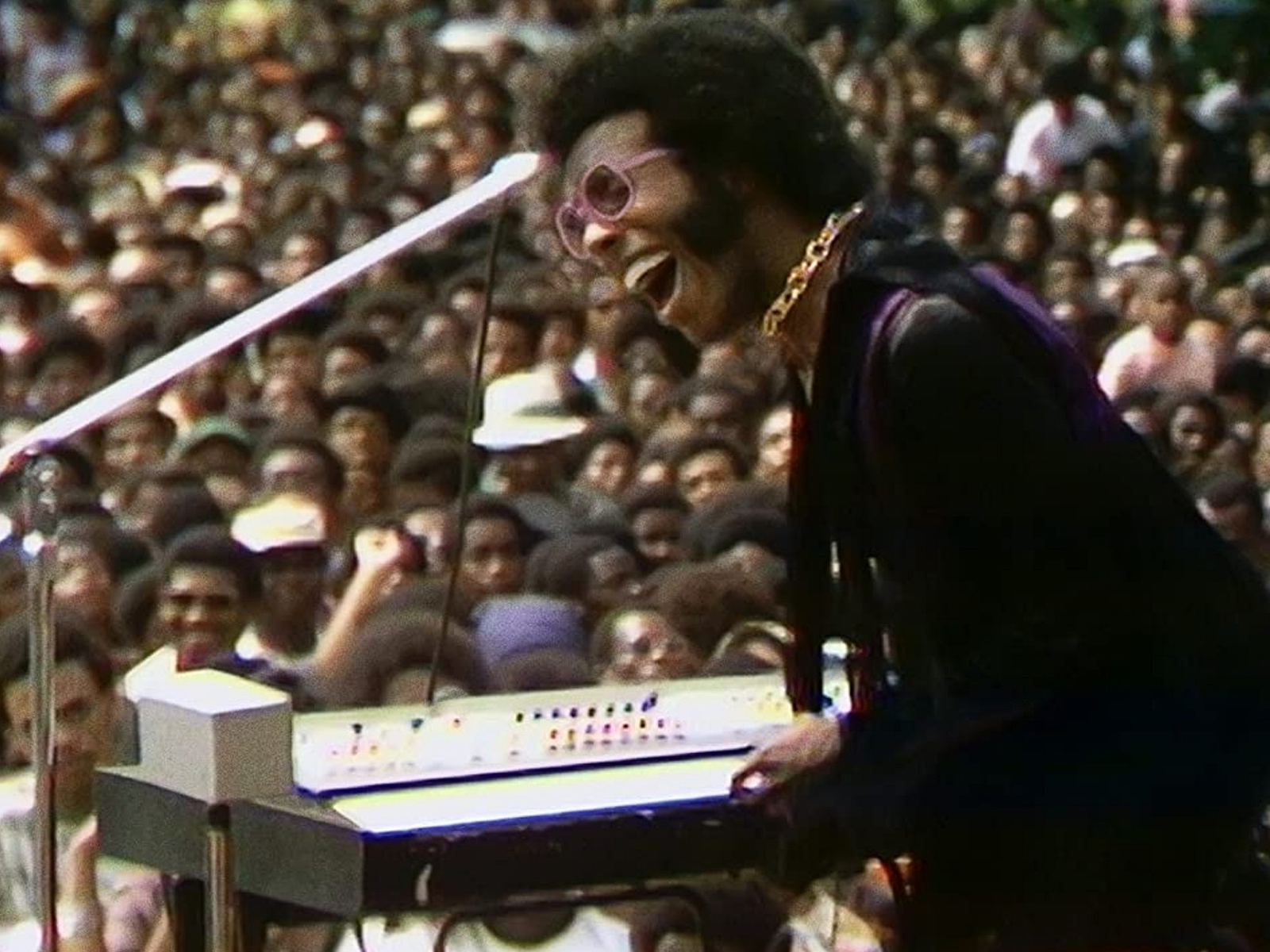

Questlove is not only a practitioner but a musicologist and “curator” of Black musical heritage – whose many forms are folded into the Roots’ repertoire. It is not surprising then that in his Sundance introduction he called the movie a continuation of his storytelling journey: and the story here is all about music as a tool of identity and political agency. We see Stevie Wonder on stage performing a driving rendition of Shoo-Be-Doo-Be-Doo-Da-Day (as well as a drum solo!). It’s an electrifying set that is lent further significance by Wonder himself who recalls the influence that period had on his transition from pop prodigy to fully formed artist and activist. That is indeed the leitmotif of this film: a Rashomon-style recollection of a collective cultural reckoning that will feel very familiar to audiences that have witnessed the events of 2020 and the rekindling of the Black Lives Matter movement. “It wasn’t just about the music,” says Gladys Knight, one of the many artists asked to comment on the clips. “We wanted progress. We were Black people and proud.”

The film features commentary by luminaries like journalist Charlayne Hunter-Gault and Chris Rock as well as Jesse Jackson who at the time joined musicians on stage to memorialize MLK with a recitation of the last moments of his life a year before, on the fatal day of his killing at Memphis’ Lorraine Motel. It is one of the emotional highlights of the film, capturing both a momentous time in history and the profound pain felt by millions of Americans. Another poignant segment is devoted to the Moon landing which took place that July. People are shown awestruck in archival news clips from around the world. The mood among the crowd in Morris Park is rather more subdued as several attendees explain: in Black America the achievement could only be measured against the backdrop of a gaping inequality of rights, wealth and justice. That sentiment would be expressed the following year by Gil Scott Heron’s “Whitey’s on The Moon”. These interviews articulate even more clearly the divide in perceived reality which shapes the national experience to this day.

Given the synchronicity, it was perhaps inevitable that the Harlem Cultural Festival concerts would be nicknamed “Black Woodstock” and that simply reinforces the unequal treatment, this time in memory, of these forgotten concerts. It also explains the film’s subtitle, “…when the revolution could not be televised” which paraphrases another Scott Heron song. As much as he tried, Tulchin could not sell his footage and these images would not be seen until today. And in a moment in which terms like “erasure” and “cancel culture” are so easily bandied about, that is a reminder of which histories and memories have actually been erased by mainstream culture.