- Fashion

The Law According to Lidia Poët: Sumptuous 1800s fashion becomes functional in this who-done-it.

The Law According to Lidia Poët is a sumptuous who-done-it with feminist overtones. It stars Italian actress and singer Matilda De Angelis (The Undoing) as the real-life heroine Lidia Poët. The leading cast includes Eduardo Scarpetta (My Brilliant Friend) as the journalist Jacopo Barberis, who may be a good guy but maybe isn’t; and Pierluigi Pasino as Poët’s brother, Enrico, who is initially exasperated by his sister’s attempt to practice law but, ultimately, becomes an ally.

The Netflix series is inspired by the life of Italy’s first woman lawyer, Lidia Poët (1855 – 1949). The story unfolds in the late 1800s, when a ruling by the Turin Court of Appeals declares unlawful the admission of Poët to the bar association. At the time she was the only female lawyer in Italy.

READ “The Law According to Lidia Poët” – First Female Lawyer in Italy by Elisa Leonelli.

The court’s decision leaves her financially vulnerable. Eschewing the offer of help from a wealthy lover, portrayed with debonair panache by Dario Aita, Lidia is forced to take refuge in the home of her lawyer brother while appealing the ruling. This is the perfect set-up for her to help Enrico in his legal cases. She applies logic and new science to prevent innocent people from being framed.

The series is fast-paced and there’s an Agatha Christie style in the way the guilty are captured. Political intrigue and the gross discrimination of women are some of the over-arching themes. The series is plush with costumes that adhere to the fashion of the time, yet gives a nod toward current sensibilities.

For instance, the domed skirts of the mid-1800s have been tapered, and it appears as though the crinoline petticoats have been parsed to create a more flattering and balanced silhouette.

These adjustments are indeed in keeping with the ‘Gay Nineties’ of the late 1800s. Technology was changing the dominant restrictions. Electricity and clothing manufacturing were the new normal. A new era of women – they worked, played sports, and pursued intellectual endeavors – was shaking things up.

Costume designer Stefano Ciammitti evokes the repressive laws towards women with the help of restrictive jackets and waistcoats. A neck adornment alludes to the challenge of competing in a man’s world. Much like the working women of the 1970s, we see the adoption of the suit and tie blouse, emulating the male uniform. In the new series women can be seen in bowties, though with a feminine twist.

Shoulders were pronounced, as is our current streetwear. Hats were less functional and more a nod to decorum.

The hues are the rich jewel tones often seen on the red carpet today. The color palette of royal purple, blue-greens, and rich red is echoed across the sets and cast.

Jackets are nipped at the waist with pronounced leg-o-mutton shoulders emphasizing the silhouette. Note the use of the cape (bottom left.) This allowed protection from the elements without compromising the exaggerated shoulders of the jackets as an overcoat might do.

The fabrics make you want to reach out and stroke them. However, the forms are never indulgent. Each garment speaks to practicality. This is a woman functioning in a man’s world. Emphasis on beauty is a detriment.

De Angelis’ natural good looks are highlighted with color and cut. The chevron pattern emphasizes the width of the shoulders and hips while ‘pointing’ to the tiny waist often belted and cinched.

The luxury of fabric is explained through a family’s fall. The reuse of items delights the informed eye. Discerning viewers will note that Poët’s red jacket makes appearances throughout the show. Waist jackets are repurposed. One might even suggest that sleeves have been removed and reused to create fresh looks.

It’s interesting to note that the only time we see her flesh while clothed, is at the opera or during evening events.

At the time women had ‘morning’, ‘afternoon’, and ‘evening’ wear. The latter allowed for an open neckline. Arms were granted some degree of public exposure.

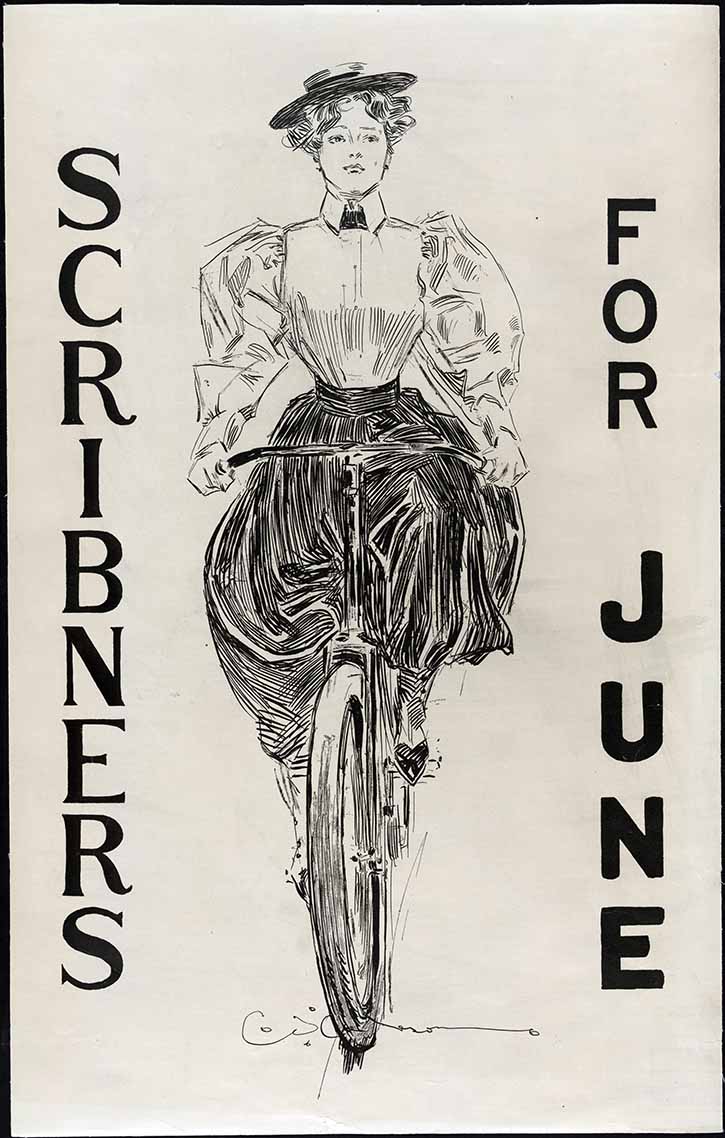

In 1892 cycling came into vogue. For women, who often did not do the typical commercial work capable of sustaining life in the city, accessing a relatively affordable means of transport meant freedom.

There is a fantastic scene that every woman will recognize. Poët has been forced to rely on her journalist friend whenever she needs to pursue a clue or test a theory. This reliance takes the form of her balancing on his bike as they cycle across the Italian countryside.

The visuals are stunning and they certainly allow for intimacy to grow. Ultimately, the forced female dependency riles, and she does what millions of women did in the late 1800s: she gets her own bike and scandalizes the male population by cycling where she needs to go. Rather than address the issue on the nose, a joyful scene unfolds of Poët trying to master the art of cycling, weighed down with layers of skirt and impractical boots.

The scene presents us more than a joyful day. We see a moment that every woman recognizes: when the clothing of the day limits their mobility and the choice is made for practicality over bowing to an outdated tradition.